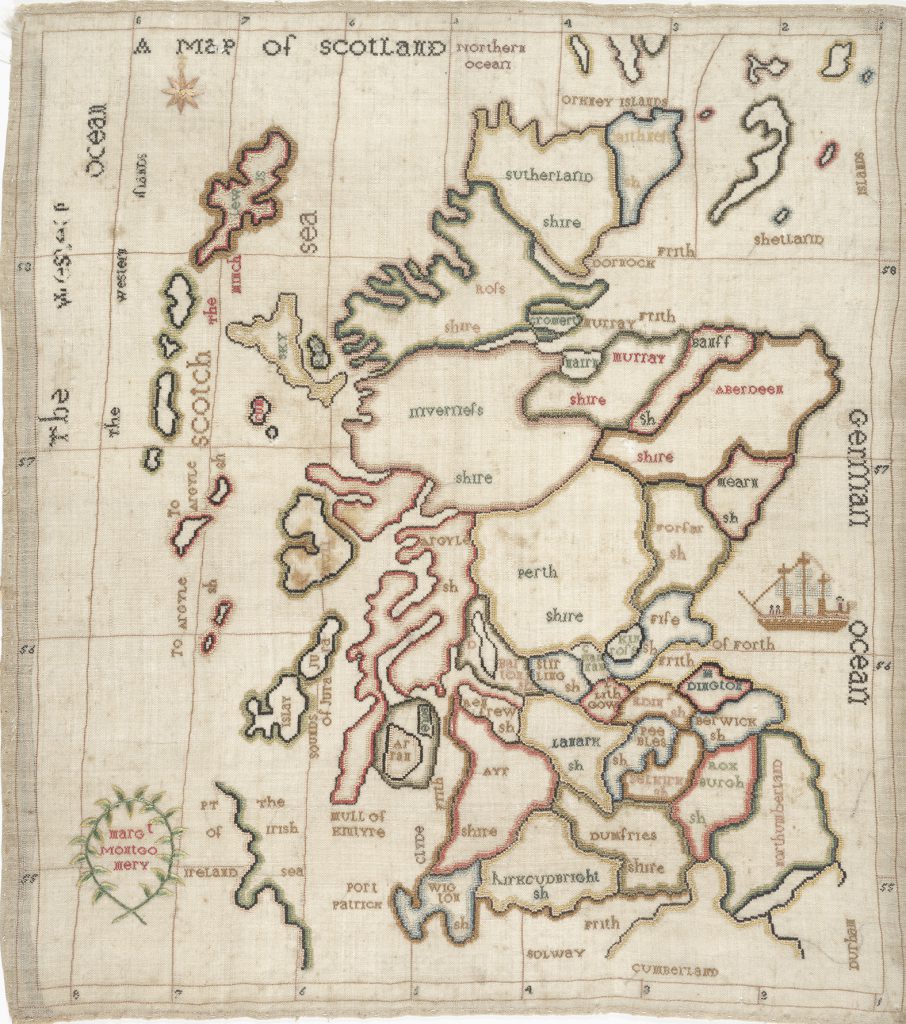

March is Women’s History Month and, in keeping with this theme, our Map of the Month is a map of Scotland, embroidered by a young girl over 200 years ago.

Map samplers such as this have historical and educational significance as over centuries their function changed from practical tools of the embroiderer, through decorative pieces, to schoolroom exercises. They play an important part in the transition in women’s education from ‘accomplishments’ in the 18th century to the more challenging geographic education and conventional map drawing found in schools in the later 19th century.

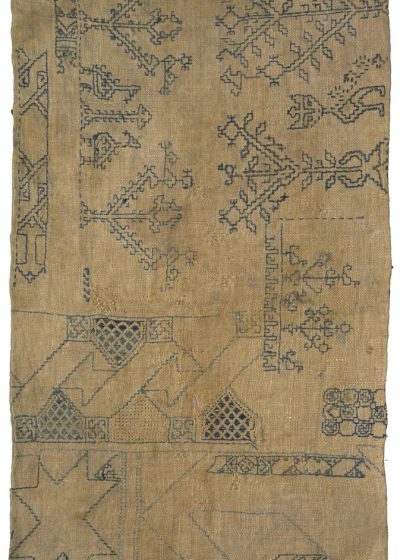

Samplers (the word comes from the Old French essamplaire, meaning ‘example’ or ‘model’) were originally created simply as a record of patterns and motifs on fabric – a method of learning stitches and storing information for future use. They had been worked for over 500 years before Margaret created her map of Scotland – the earliest surviving examples date from the 14th-15th centuries. The example below, a piece of linen found in Egypt, shows the random patterns and different stitches typical of the earliest samplers.

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

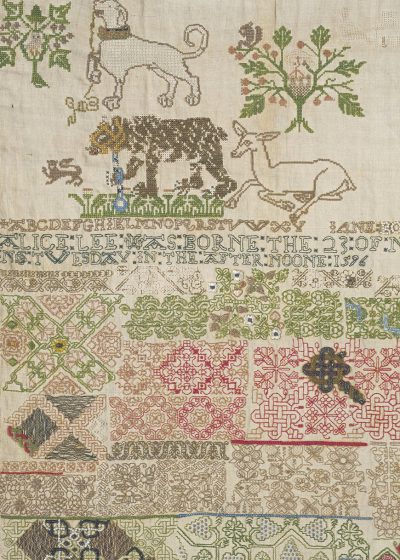

By the time of the first dated British example, created by Jane Bostocke in 1598 (below), there is already a move away from samplers being used simply for recording patterns, and being used more to demonstrate the embroiderer’s skill.

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

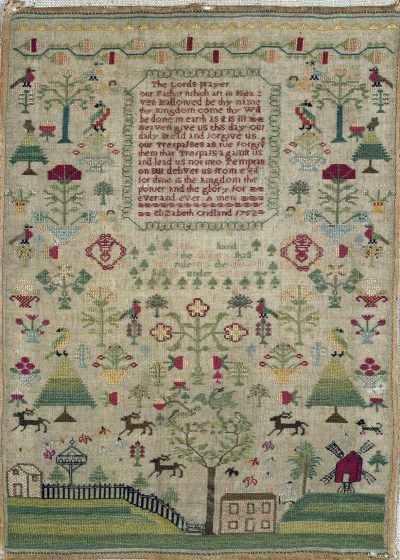

Over time, alphabets regularly came to be included in samplers, suggesting that sampler-making was becoming more significant as an educational exercise. Moral and religious inscriptions were often added and samplers were seen as signs of virtue, achievement and industry. Girls were taught the art from a young age and, along with alphabets and verses, pictorial elements were added. Samplers became more decorative, with architectural motifs, landscapes, and symmetrically placed animals, birds and plants (example below).

Image © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

By the 18th century, the teaching of needlework in schools was actively encouraged. Educational themes became more common and included multiplication tables, perpetual calendars – and maps.

Events of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries led to an explosion of interest in geography. This was the time of the American and French Revolutions, wars between France and England and Captain Cook’s voyages. Interest in geography grew and became fashionable, there was a growing interest in foreign travel and the study of places became important and exciting.

By the beginning of the 19th century, when Margaret Montgomery created her map of Scotland, samplers were almost entirely worked in cross stitch and were created more to demonstrate knowledge than to preserve needlework skills. Geography was the first science taught to girls in school and map samplers were considered an excellent way of learning.

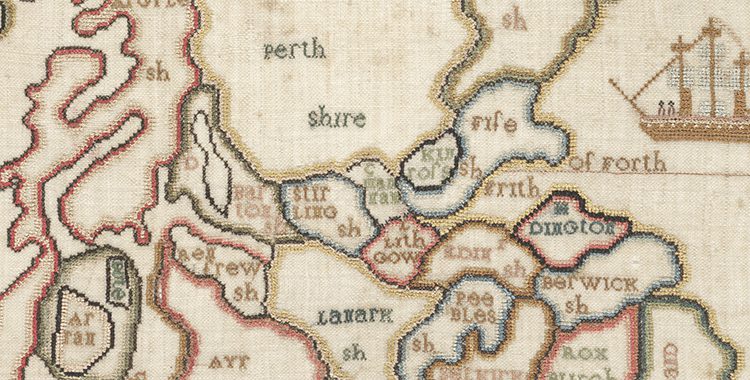

It was no doubt hoped that Margaret would learn about the shape and geography of Scotland by stitching the name of each county and painstakingly shading each county boundary.

Interestingly, only one town has been included – Port Patrick, at the south west of the country. Perhaps this reflected its importance at the time as the main ferry point for the north of Ireland. Perhaps this was her nearest town. Or perhaps she began stitching place-names at the south west corner of the map, and then decided not to add any more.

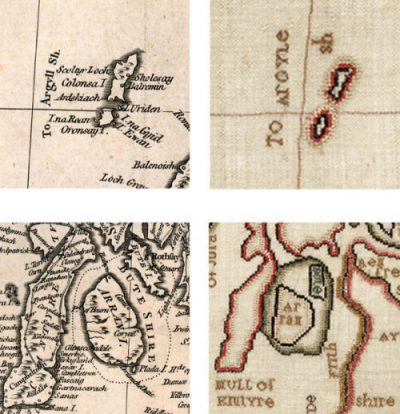

Although this is a finely-worked piece of embroidery, it’s not entirely accurate, geographically. This suggests that Margaret may have copied or drawn the outline herself. We do not know how old Margaret was when she embroidered the map, but the slightly haphazard spacing of place-names suggests an inexperienced hand. In many places she had to squeeze the county names into the appropriate space, and sometimes shorten them to fit (on some occasions she has demonstrated her own form of shorthand, which may have bemused those not familiar with the names).

Other map samplers, more accurately drawn, were likely to have been prepared by a teacher or governess before being stitched by the pupil. Samplers depicting maps, first drawn onto the canvas by the pupil or her teacher, became so popular that printed satin or paper versions could be purchased ready to embroider.

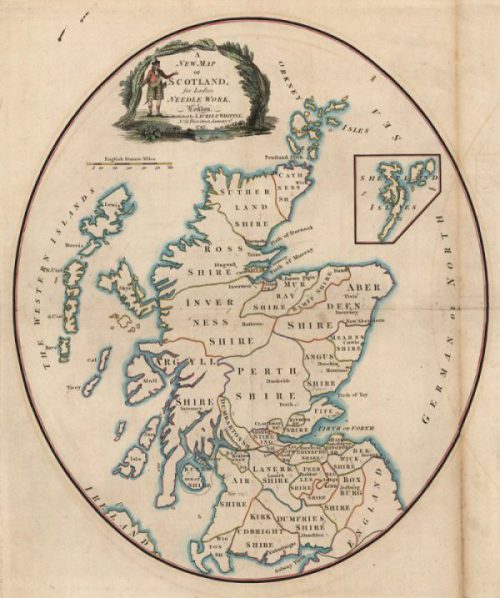

During the late 18th century, map publishers Laurie and Whittle (Fleet Street, London) produced maps of Scotland and Ireland intended for this popular market in ladies needlework. Maps were either printed directly onto silk for embroidering or as a fine paper template, which was laid onto a ground fabric, generally of silk, and stitched through (example below).

NLS shelfmark: EMS.s.699

Although this map template would have been in existence at the time Margaret Montgomery was creating her sampler, there are several features (including the oval border and the position of the Shetland Isles) that suggest she did not use this map as a basis for her sampler.

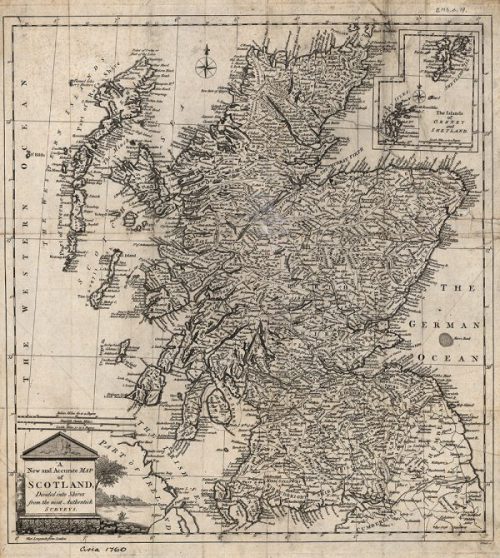

Margaret’s needlework map is rather unusual in that it shows Scotland alone – there are many more surviving samplers showing England and Wales (sometimes including part of southern Scotland) or Europe. It is also curious because it includes the grid for latitude and longitude. This is one of the reasons that it is thought to be based on ca.1767 map published in A general history of Scotland, from the earliest accounts to the present time by William Guthrie.

NLS shelfmark: EMS.s.19

The embroidering of map samplers in schools came to an end in the middle years of the nineteenth century when the teaching of needlework in general started to change. With the increasing use of globes and availability of cheaper printed geographical maps and atlases, the fashion for embroidered maps declined.

The full map/zoomable image can be seen at http://maps.nls.uk/view/74417597