Scottish literature has a strong tradition of novels of working-class life by working-class authors. Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s ‘A Scots Quair’ (1932-4), William McIlvanney’s ‘Docherty’ (1975), James Kelman’s ‘The Bus Conductor Hines’ (1984) and Irvine Welsh’s ‘Trainspotting’ (1993) are among the classic works of Scottish proletarian literature. The only two Scottish novels that have won the Booker Prize, James Kelman’s ‘How Late it was, how late’ in 1994 and Douglas Stuart’s ‘Shuggie Bain’ (2020) are set in a working-class milieu.

Tom Hanlin (1907-1953) was a celebrated and bestselling exponent of Scottish proletarian literature but is now largely forgotten. Born in Armadale, West Lothian on 28th August 1907 he showed promise at school and had a childhood ambition to be a writer, but family circumstances meant he had to leave school at fourteen. He worked on a farm for a year and then at fifteen went down the mines, where he worked for the next twenty years. He did not give up his writing ambitions though and whilst working as a miner studied journalism in the evening. In 1942 a workplace accident led to him spending three months in hospital where he passed the time by writing short stories. One of these ‘Sunday in the village’ won the Sheffield University Prize, a literary competition for “manual workers in or about a coal mine or have been injured when so employed”.

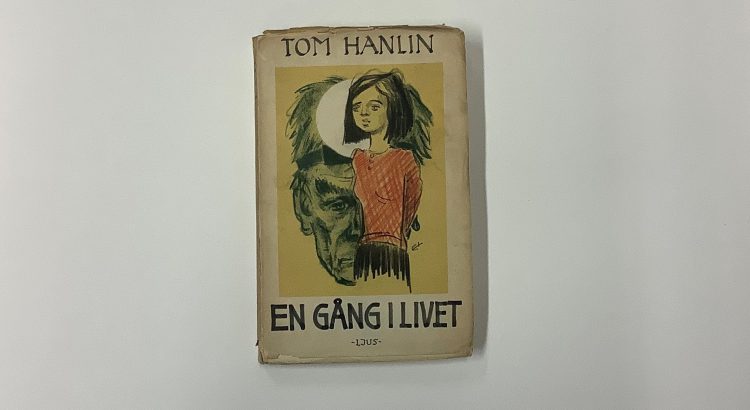

His first novel ‘Once in every lifetime’ won the Big Ben Fiction prize in 1944, £500 and a publishing deal. When the book appeared in 1945 this statement appeared on the book jacket. “When Tom Hanlin, who is a miner from the West Coast of Scotland, first sent us his novel for our “Big Ben” competition, he assured us, that once we had started reading it, we should not be able to put it down. This (to our exasperation) we found to be true”. The reading public seemed to agree as the book sold 250,000 in the first three weeks after publication. The novel was also widely translated, the illustration above is the cover for the Swedish translation from 1946. John Steinbeck called it “A wonderful, young, strong, true book.”

Hanlin would publish three additional novels including ‘The miracle of Candlerigg’ which tell the story of two hundred Scottish miners trapped underground by an accident. He wrote plays for radio and found a ready and lucrative market for his short stories in British and American magazines.

His story ‘The Alien Corn’ appeared in the March 1947 edition of the ‘Atlantic Monthly’. The story starts as follows.

This story is about the time I was seventeen and worked on the night shift in a pit. Working in a pit was all the kind of work I knew, the night shift was the only kind of shift I could get, and staying where I was, was the place where my kind of people stayed. Where I was born and brought up, you got it shoved down your throat that you ought to be thankful that any work came to you at all. When none came your way, you just moved some other place.

You can read the complete story on the website of the magazine here.

Hanlin was well established in his second career as a writer. Hollywood even came calling with offers of scriptwriting, but he turned them down as he wanted to pursue his own literary path. Sadly, it was not to last as in the late 1940s he developed heart and breathing problems. He died on 7th April 1953 at the age of forty-five. He leaves behind a legacy of novels, short stories, and radio plays. Today he is a largely forgotten figure, his books long out of print. You can find and read them at the National Library of Scotland.

Tom Hamlin’s accounts of working life may lack the lyricism of Lewis Grassic Gibbon or the harsh, gritty realism of the work of the Angry Young Men such as Alan Sillitoe and David Storey that would appear a few years later, but they deserve an audience. He is a fine storyteller and an expert at capturing the minute details of everyday life. English novelist and creator of ‘Dick Barton, special agent’ Norman Collins wrote of Hanlin’s debut novel in the ‘Observer’ “It is brief, moving in places, almost unbearably so, and often beautiful. In short Mr Hanlin is a remarkable fellow”.