Ever wondered about what kind of news people were reading in Scotland over 300 years ago? What kind of small advertisements were appearing in print? How, in an age where travel and communications were slow and difficult, a newspaper’s editor managed to find news to print while worrying about government censorship?

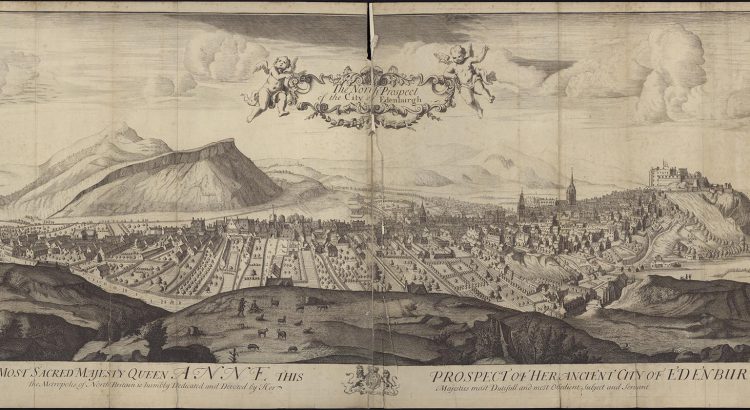

You can find out here the story of the “Scots Courant,” the first long-lasting Scottish newspaper, published from 1710 to 1720. The Library has an almost complete run of all its issues and our holdings of the “Scots Courant” can now be viewed online in our Scotland’s News feature on our Digital Gallery.

Government censorship

Early versions of newspapers had been around in Britain since the early 17th century. However, it wasn’t until the 1690s that newspapers became properly established in Scotland. The printing of the news was initially subject to strict government control. The Privy Council in Scotland, the powerful body that advised the Scottish monarch, was responsible for licensing and censoring any news-related publications, such as the “Scots Courant”.

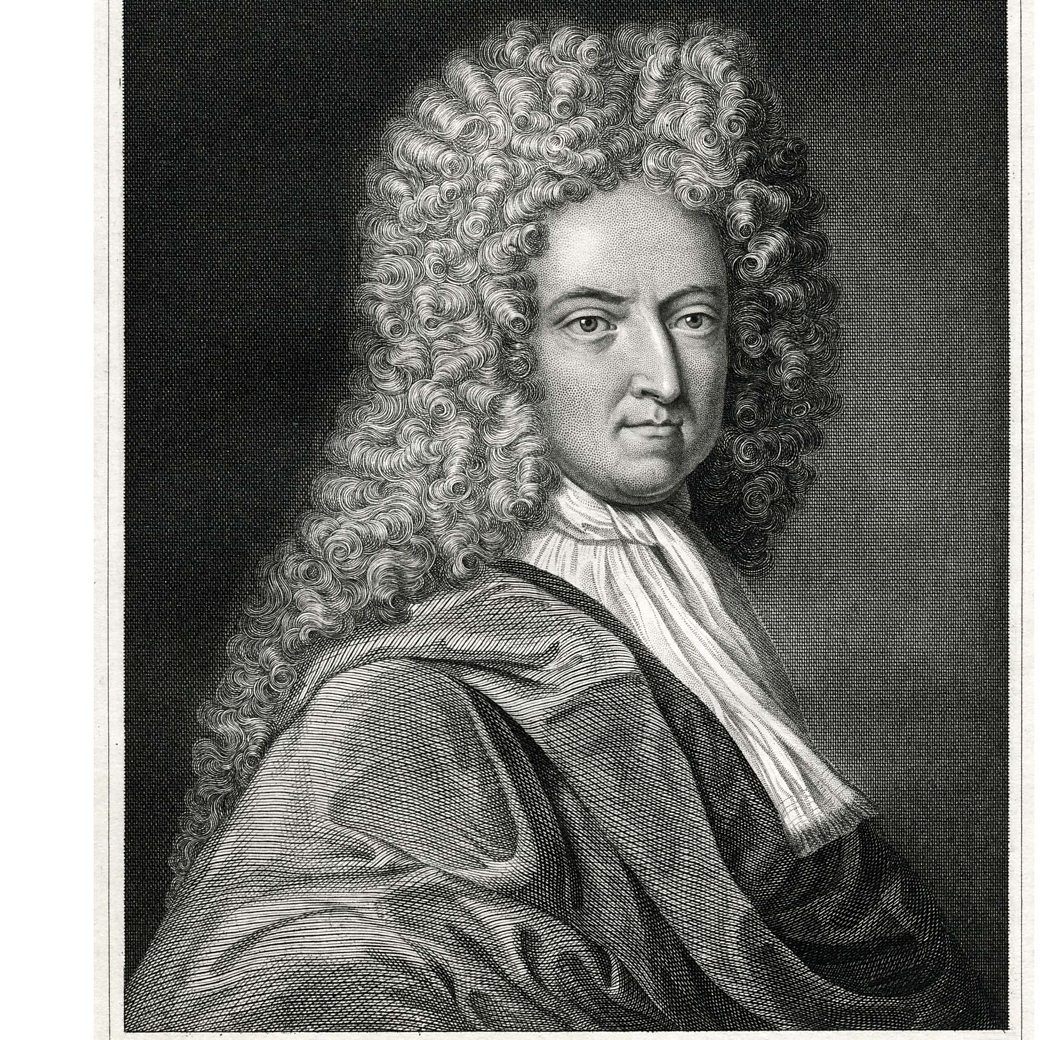

The “Edinburgh Courant” and Daniel Defoe

The “Scots Courant” was the successor to the “Edinburgh Courant” published by Adam Boig. When Boig suddenly died in January 1710, the warrant to publish a paper of that name expired with him. The Privy Council then authorised the English writer and businessman Daniel Defoe, later to find fame as the author of the novel “Robinson Crusoe,” to publish the “Edinburgh Courant.” Defoe had been dividing his time between Edinburgh and London since 1706, having worked as an agent for the political union between England and Scotland in 1707.

Defoe took a few a weeks to organise the publication of his new version of the “Edinburgh Courant.” Meanwhile, the printer John Reid Jr., who had been printing the newspaper and selling it from his premises in Lib(b)erton’s Wynd in the Old Town since 1709, boldly kept on printing it. Reid may have assumed that Defoe was never actually going to publish his newspaper.

Birth of the “Scots Courant”

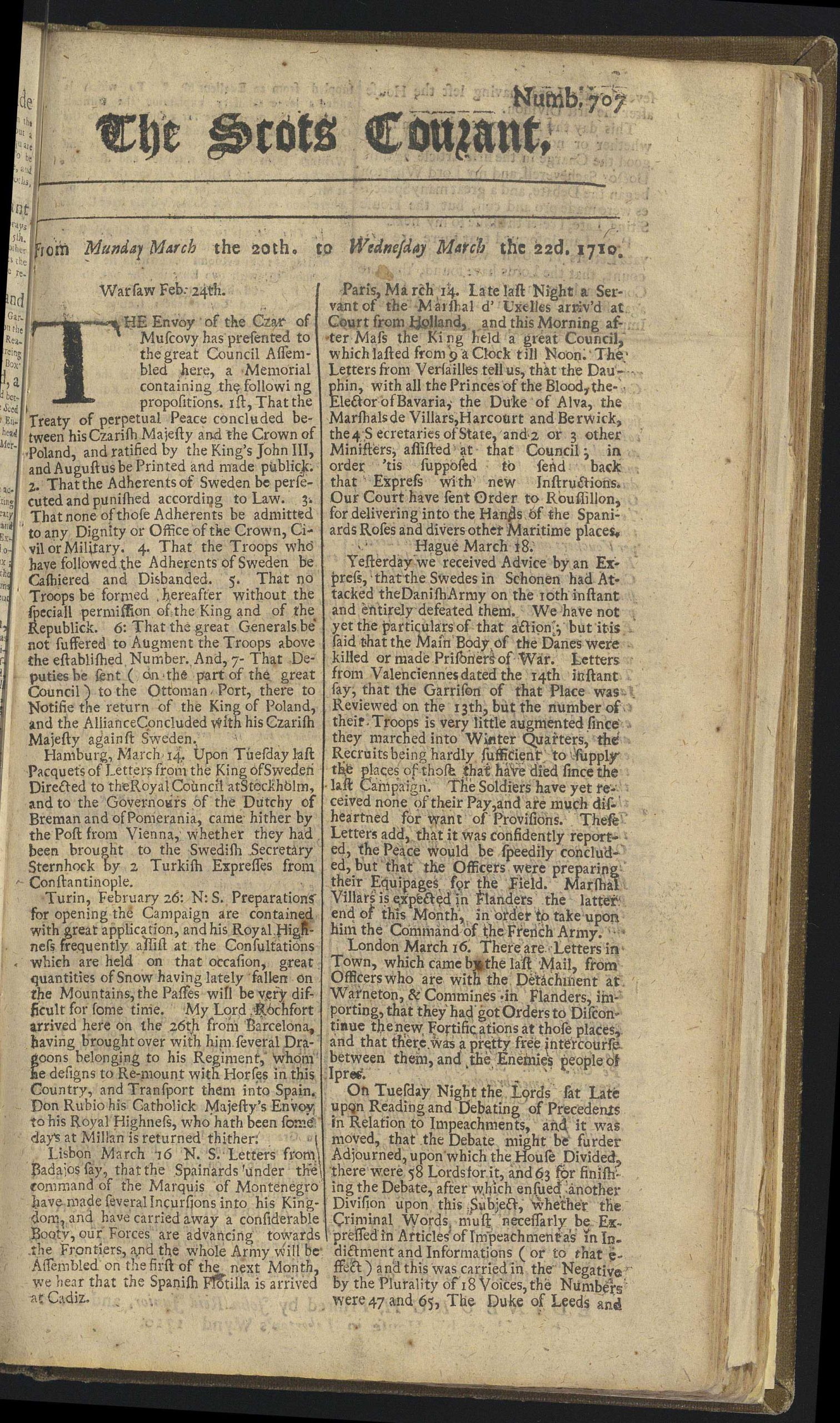

When Defoe’s “Edinburgh Courant” did appear in print on March 20th, Reid realised he couldn’t challenge Defoe’s right to publish with this title. Defoe had the Privy Council permission to do so, as was made clear by the wording under the title of his newspaper when it finally appeared, “Published by authority”.

Reid quickly gave his newspaper a new title, the “Scots Courant.” His new title continued the numbering of the original “Edinburgh Courant”, the first issue being number 707 for March 20th to March 22nd, 1710. Reid maintained Boig’s political stance, which was pro-Jacobite, sympathetic to the cause of the exiled Stuart royal family of the late King James II, and disapproving of the union with England. He needed to appeal to the newspaper’s current readership, who probably disliked the idea of a pro-Union outsider, Defoe, taking over a Scottish newspaper.

Ironically, Defoe’s newspaper only lasted for two issues before he returned to England, drawn south by political turmoil in London. He did not return to resume his publishing venture in Edinburgh.

Publishing the Scots Courant

By modern standards, the “Scots Courant” was a rather modest publication. It appeared three times a week and was a news-sheet, a single, small folio-size sheet, printed on both sides. Occasionally two sheets were printed, depending on how much news was available. The print run would have been small, in the tens rather than the hundreds, and copies would have been sold locally in the Edinburgh area.

The price of the newspaper first appears in issues from July 1712 onwards (it cost one penny). Newspapers had strong competition from news-related broadsides, single sheets printed on one side, focussing on a single event. Broadsides were cheaper and distributed more widely through Scotland through hawkers and pedlars, who sold them in public places.

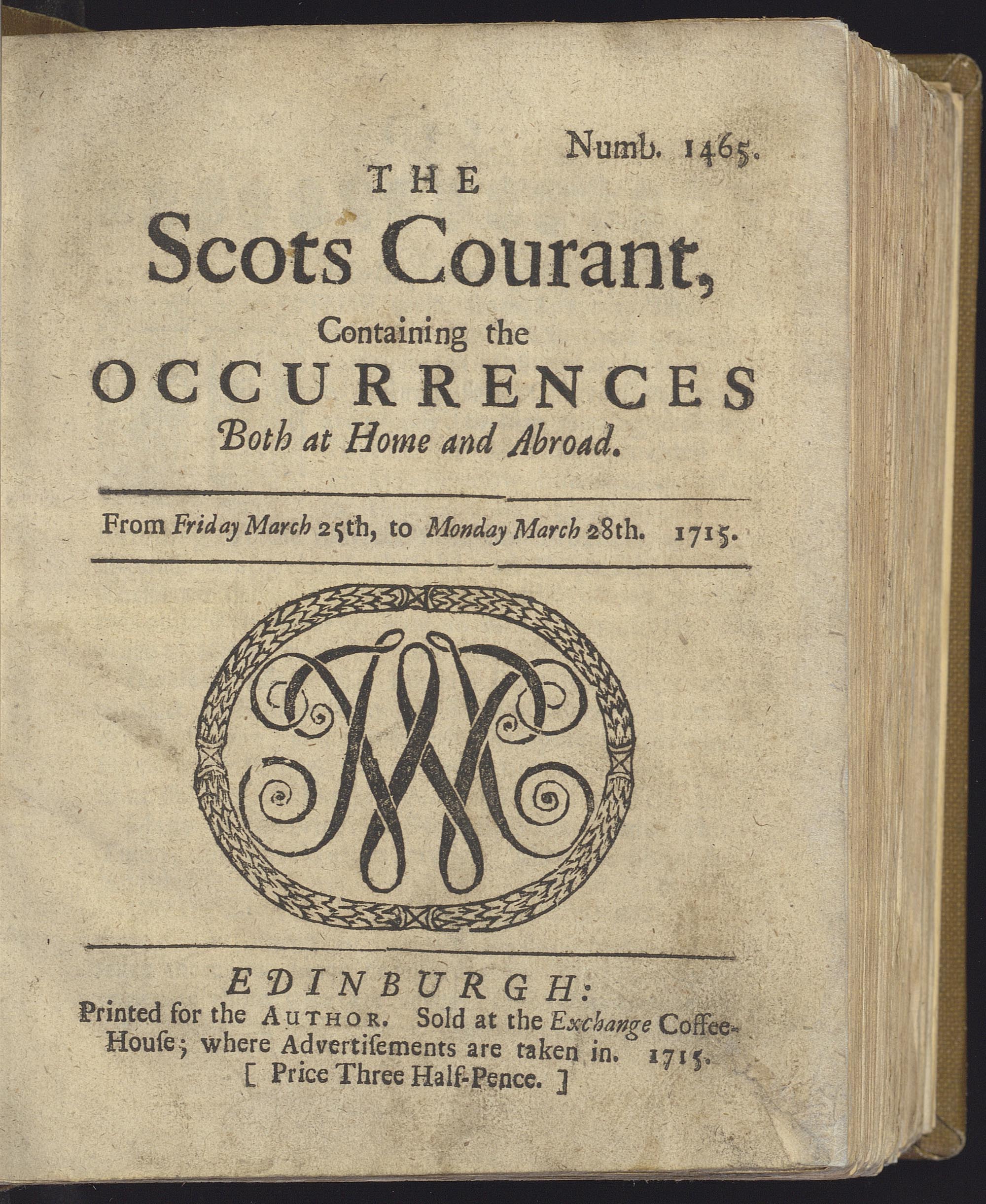

In May 1710, James Watson of Edinburgh, one of Scotland’s best and most experienced printers, took over the printing and publication of the newspaper. It was now sold at the Exchange Coffee House in Edinburgh, where the well-to-do and professional classes (such as lawyers and merchants) of the city met in a more civilised atmosphere than the local taverns.

In March 1715, the newspaper changed format to a news-book, a small pamphlet of 12 pages, and the price was up to three half-pence. It kept this price and format for the rest of its run.

Foreign news and small ads

The text was printed in two columns with news from the Continent or London occupying the first page and part of the second. There were no headlines, editorials or illustrations to attract the reader. The overseas news had a strong emphasis on military events. Sometimes the text of British government proclamations would be reproduced or speeches in Parliament.

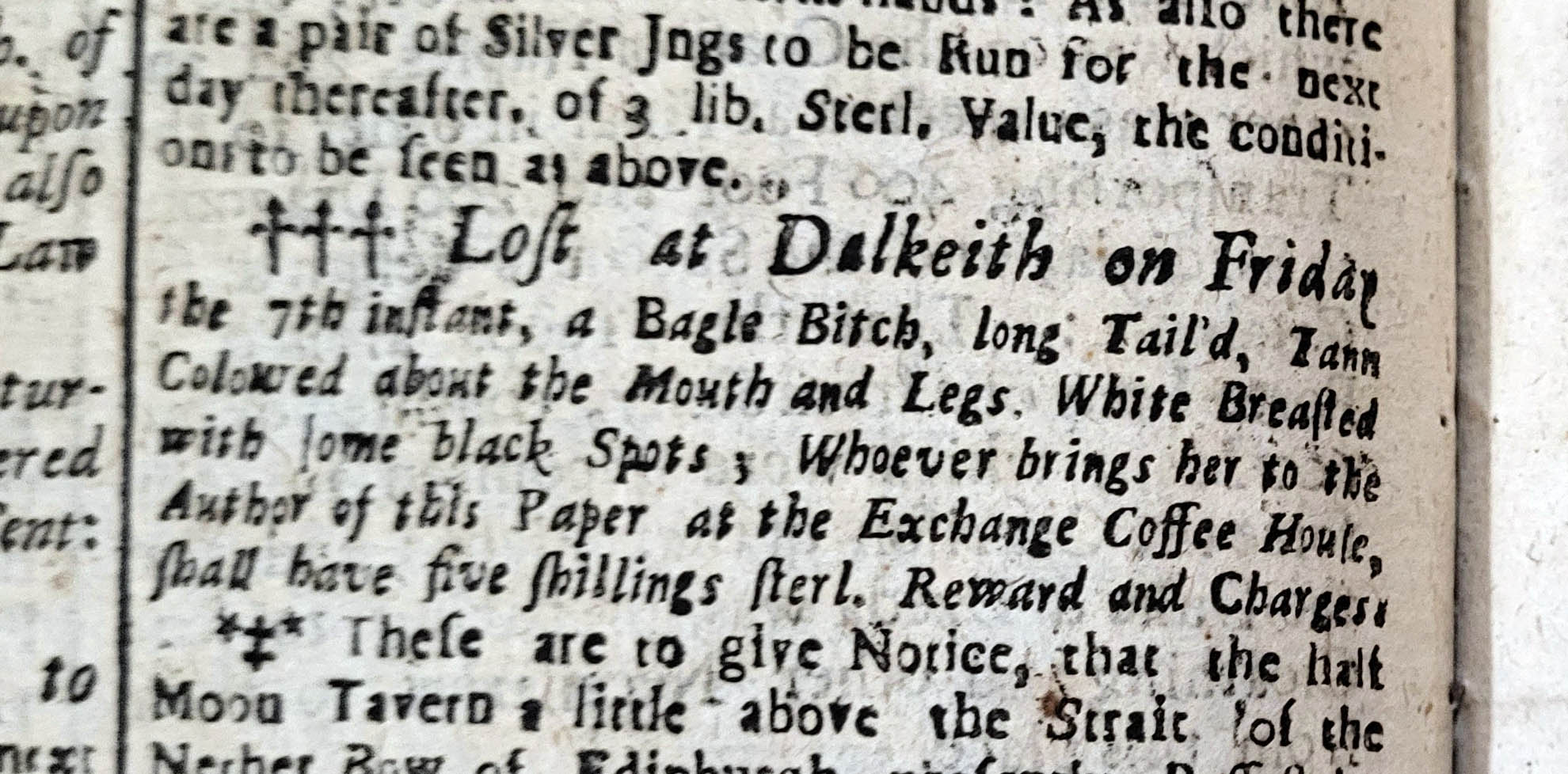

The second page usually included brief news from Edinburgh and the surrounding areas. These Edinburgh sections were often little more than introductions to the advertisements. The advertisements are particularly useful for the modern reader by giving an impression of everyday life in Scotland. You can read about new publications for sale in the shops, property and speciality foods for sale, notices of lost property and pets, and sales of livestock. As with modern newspapers, attracting advertising revenue was hugely important to keep the newspaper financially afloat.

James Muirhead as author and editor

As a single sheet publication, the “Scots Courant” only required one person to bring the content together, edit it and organise the printing. When James Watson took over the newspaper, James Muirhead is mentioned as the “author of this paper”, who was available at the Exchange Coffee House to take in advertisements. Muirhead appears to have been involved with the newspaper throughout its run. From November 1719 onwards, the newspaper was for sale at Muirhead’s own coffee house.

Muirhead had to ensure there was enough news content for the newspaper. Sources of information would have included the most recent issues of the London newspapers and letters, brought to Edinburgh in the mail coach. These coaches were not frequent, probably only one coach arrived a week at this time. The contents of the London papers were recycled for the Edinburgh readers. Muirhead would also have relied on people in sending news in letters and on talking to the well-connected visitors to the Coffee House who had information to pass on.

Scottish news and the Jacobite Rising of 1715

Due to poor roads and communications, events in Scotland were only covered in a patchy manner and usually related only to Edinburgh and surrounding areas. The problems in the supply of current Scottish news were highlighted by one major event in Scotland during the 1710s, the short-lived Jacobite Rising of 1715. The supporters of the self-styled James VIII/III, the son of the late King James VII/II who was living in exile in France, started a military campaign in North-East Scotland and the Central Highlands intended to overthrow the Hanoverian King George I and the Westminster government. An uprising in favour of the ‘Old Pretender’ James was also initiated by Jacobites in the North West of England.

Despite the Jacobite sympathies of his readers, James Muirhead had to be mindful of the Privy Council’s close attention to the newspaper’s content during this period. The tone of the “Scots Courant” coverage was either neutral or pro-British Government. During the months of the uprising, it was often broadsides, printed more quickly and sometimes closer to the action, which had more up-to-date news and insights. Muirhead was removed from the events in Edinburgh and sometimes had to reuse their content in his newspaper.

End of the Scots Courant

The final issue of the “Scots Courant” was published on 22 April 1720. In the ten years of the newspaper’s existence, at least nine other titles had come and gone in Scotland. To have lasted for ten years is such an unstable market was some achievement. Since 1718 a major Edinburgh rival was being printed, the pro-Union “Edinburgh Evening Courant”. It was probably no coincidence that a week after the end of the “Scots Courant” a new, pro-Jacobite newspaper the “Caledonian Mercury” was published. The “Mercury” would become the main rival of the “Edinburgh Evening Courant” for the next 100 years.

Further reading:

Stephen W. Brown, “The market for news in Scotland” in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, vol. 1, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023, pages 285-308.

W.J. Couper, “The Edinburgh periodical Press,” vol. 1, Stirling: Eneas MacKay, 1908.

Anette Hagan, “Case Study 10: Reading the news in Scotland: the Jacobite Rising of 1715” in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, vol. 1, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023, pages 280-284.

Alastair J. Mann, “The Scottish book trade, 1500-1720”, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, 2000.