Can you imagine living in a time where the news only appeared three days a week? In 18th-century Scotland that was normal; but for us, living in an era of 24-hours rolling news, 365 days a year, it would be very strange. In 1776 one Edinburgh newspaper owner, John Robertson, dared to be different. He started publishing the news on a daily basis with “The Caledonian Mercury” and the supplementary title “The Caledonian Gazetteer“. You can find out here whether his experiment with Scotland’s first daily newspaper succeeded.

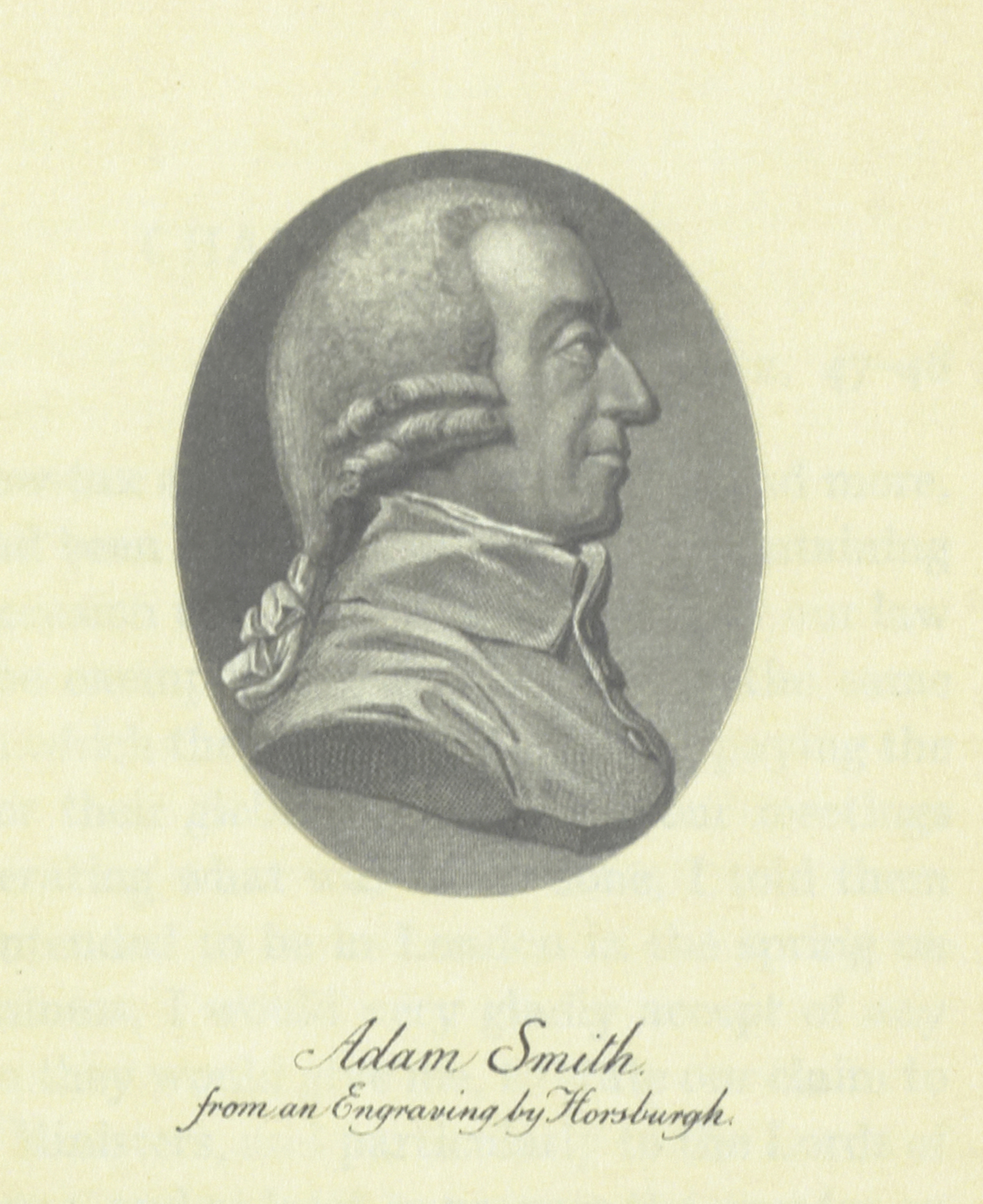

1776 was the year that American colonists started a revolution against British rule that changed the world forever and a Scottish author, Adam Smith, published a ground-breaking book, the “Wealth of Nations.”

You can look online at all our issues for the year 1776 of “The Caledonian Mercury” and “The Caledonian Gazetteer,” as part of our Scotland’s News feature on our Digital Gallery.

Birth of an institution

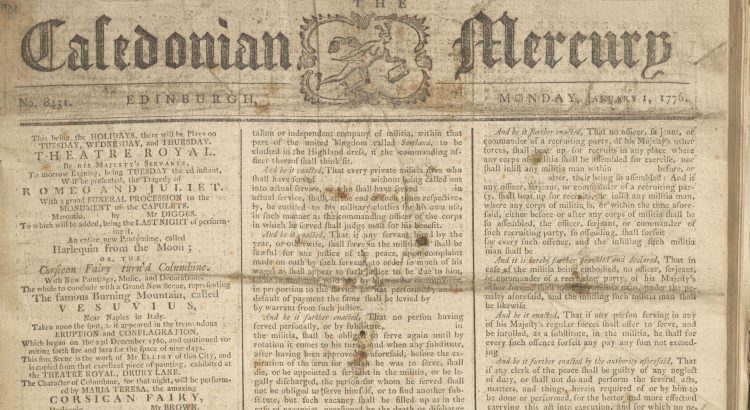

The “Caledonian Mercury” was launched in April 1720 as a thrice-weekly newspaper by the printer William Adams Jr. and William Rolland. It was an early version of a broadsheet format newspaper, printed on large folio-size paper. In 1724 Thomas Ruddiman took over as editor and publisher.

The newspaper’s main rival was the “Edinburgh Evening Courant,” established in 1718. The two Edinburgh newspapers dominated the Scottish newspaper scene in the 18th century, even after other Edinburgh-based competitors appeared on the market from the 1750s onwards. The “Edinburgh Evening Courant” was firmly for the political union with England and British in its outlook. The “Caledonian Mercury” was more focused on Scotland and sympathetic to the cause of the Jacobites, followers of the exiled Stuart royal family who still hoped to regain the British throne.

John Robertson as owner

In 1772 the Edinburgh printer and bookseller John Robertson bought the newspaper from the family of Thomas Ruddiman, taking on the duties of publisher and editor. The newspaper was priced at three pence and at this time was sold mainly to subscribers, guaranteeing a regular income. However, advertising revenue was also important to finance its publication. By the time Robertson became owner, adverts could make up as much as 75% of the newspaper’s content, along with lengthy notices of theatre performances in Edinburgh.

Daily news and the “Caledonian Gazetteer”

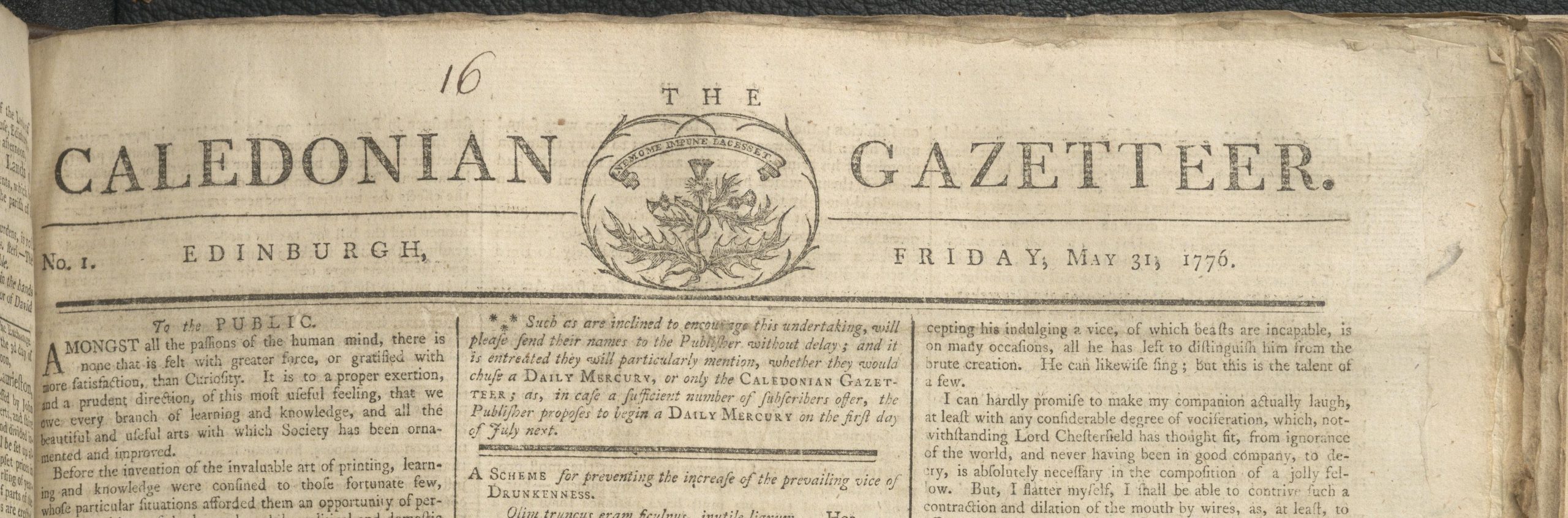

The first regular, daily English newspaper had appeared as early as 1702, the “Daily Courant” of London. It would take Scotland another 74 years for someone to take this step. Rather than risk publishing the “Caledonian Mercury” on a daily basis, John Robertson created a supplementary title, the “Caledonian Gazetteer,” to give his readers access to the news for six days a week instead of the usual three. The “Gazetteer” was published on the three days of the week that the “Mercury” was not. (Sundays were off limits for printing due to the religious conventions of 18th-century Scotland).

Robertson had plenty of advertising to fill his new newspaper, first published on May 31, 1776, but he lacked sufficient news to print. As with earlier Scottish newspapers, Robertson was heavily dependent on the contents of the London post and newspapers for news on events overseas and south of the Border. After 13 issues he stopped the “Gazetteer”. In the issue of the “Caledonian Mercury” for July 2nd Robertson revealed that he was now experimenting instead with printing the “Caledonian Mercury” for five days a week. There would be no newspaper on Thursdays, as no post arrived from London that day.

However, after the issue for August 31, the “Caledonian Mercury” reverted back to being a thrice-weekly publication. Robertson could not cover the additional expense of printing five days a week. He implied that the reluctance of subscribers to part with three pence more than three days a week had also helped to put an end to Scotland’s brief experiment with a daily newspaper. Daily newspapers would finally become possible in Scotland in the next century, thanks to improved nationwide communications and the invention of machine presses to lower the costs of printing.

Trouble brewing in America

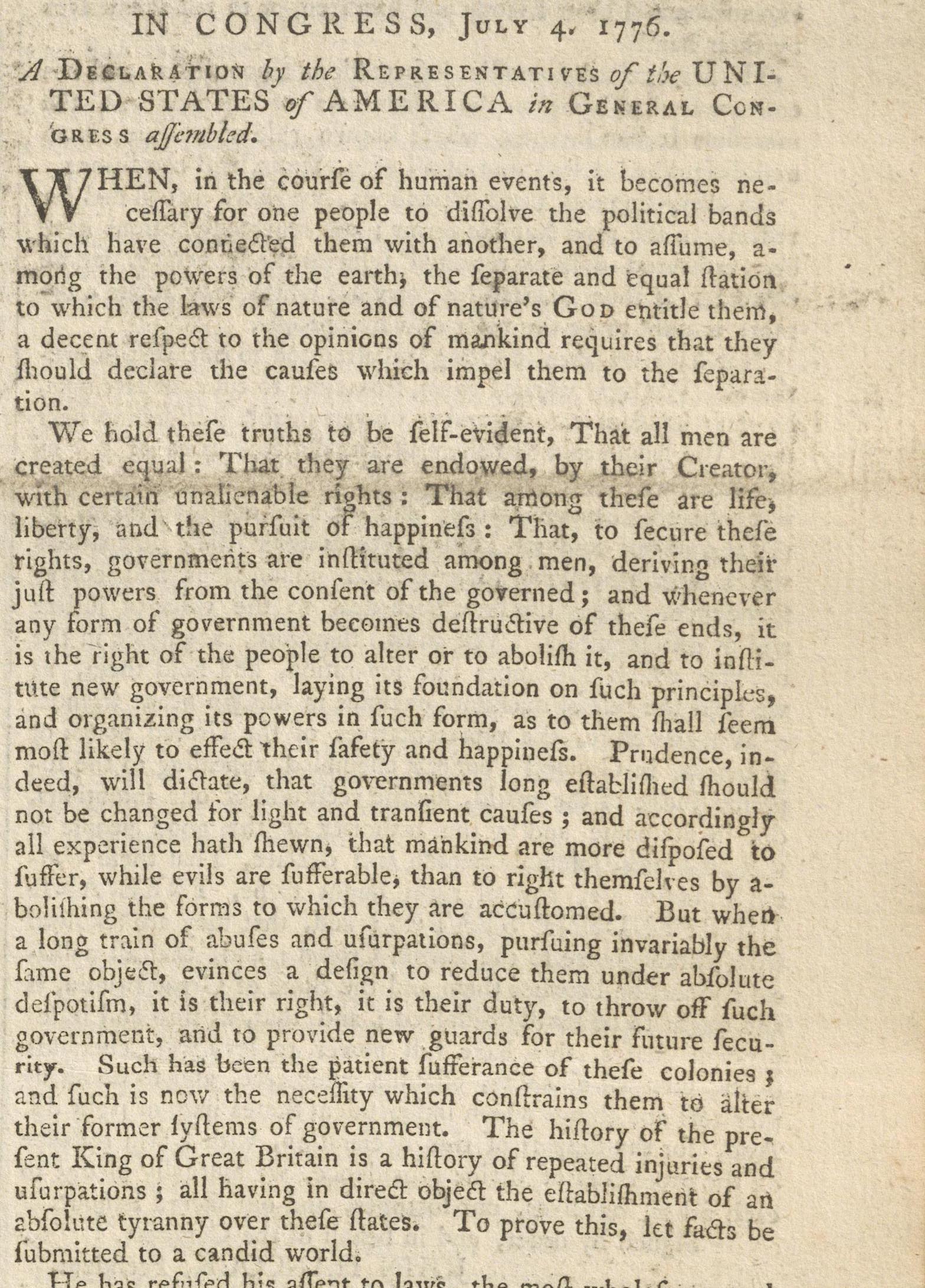

The year 1776 would see Britain’s empire face a major threat: the armed uprising of the American colonists against direct British rule. The state of rebellion was confirmed in 1776 in Philadelphia, when the Second Continental Congress declared King George III a tyrant who had trampled on the colonists’ rights as Englishmen. On July 2, 1776, the Congress declared that the colonies considered themselves “free and independent states”. Two days later, on July 4, 1776, the Congress unanimously adopted the Declaration of Independence, which embodied the political philosophies of liberalism and republicanism, and proclaimed that “all men are created equal”.

Reaction in Scotland

News took a long time to cross the Atlantic, and then it would have to travel from London to Edinburgh. It took several weeks for the editor of the “Caledonian Mercury” to report and comment on actual events in America. The newspaper had always represented a pro-Jacobite tradition with a suspicion of the Westminster government, so it was understandable that the American colonists’ cause would receive a fair hearing. In the spring and summer of 1776, the “Caledonian Mercury” printed extracts from the English author Thomas Paine’s recently published pro-American independence pamphlet “Common Sense”.

The text of the Declaration of Independence was first printed in the “Caledonian Mercury” on 20 August, almost two months after the event (it had already appeared in rival newspaper the “Edinburgh Advertiser” in the issue covering 16-20 August).

Subsequent issues of the newspaper carried letters from the public, mostly hostile to the American colonists, although the newspaper did print one letter from an American patriot, justifying the rebellion.

Newspapers of the period usually avoided taking a strong line on political events. They were looking to appeal to as wide a readership as possible and did not want to alienate their public. Robertson maintained a neutral and factual tone in reporting the events of the conflict in 1776. He would have been aware that public sympathy in Britain for the American colonists largely disappeared after the Declaration of Independence was first reported in August 1776. He would also have been worried about government interference in his newspaper if he had dared to support the American cause.

A revolutionary book is published

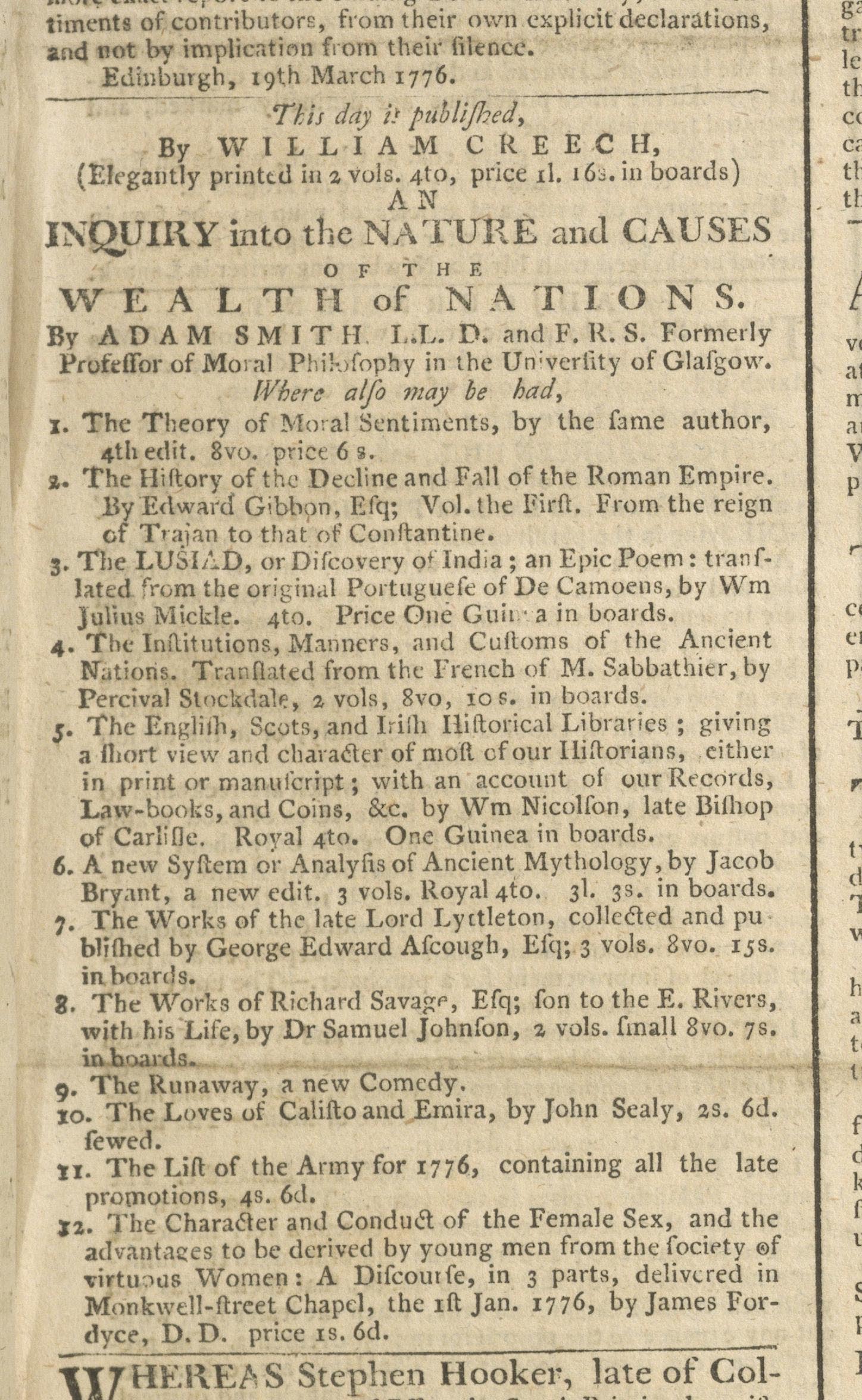

An advertisement in the “Caledonian Mercury” for March 18th, 1776, reveals that copies of “An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations,” by the Scottish philosopher and political economist Adam Smith, were now on sale in Edinburgh at the shop of William Creech.

The two volumes in the publisher’s pasteboard binding cost £1 16 shillings (around £350-400 today), putting it beyond the means of all but the wealthiest classes of society. Sadly, there were no book reviews in the newspaper at this time. The book was, however, well received by those who could afford it and has been incredibly influential on Western political and economic thought right up to the present day.

The end of ‘Granny Mercury’

Robertson sold the newspaper in 1790. The “Caledonian Mercury” would continue to be published under various owners until April 1867, before it finally bowed to the competition provided by better-resourced titles. At the time of its closure, it was known as ‘Granny Mercury’ due to its long history and its homely, old-fashioned reputation. The “Scotsman” newspaper bought out the title and the name of the defunct paper was allowed for a time to appear as a subtitle of the “Weekly Scotsman”, but it was eventually dropped there too.

Further reading:

Rhona Brown, “The Scottish press” in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, vol. 1, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023, pages 268-279.

Stephen W. Brown, “The market for news in Scotland” in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, vol. 1, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023, pages 285-308.

W.J. Couper, “The Edinburgh periodical Press,” vol. 2, Stirling: Eneas MacKay, 1908.

Nicole Greenspan, “Newspaper and War” in The Edinburgh History of the British and Irish Press, vol. 1, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023, pages 472-489.