The choice: Reminiscences of Thomas Marshall of Berwick, (Berwick-upon-Tweed, 1835)

Chosen by: Graham Hogg, Curator (19th-Century Printed Collections and Photo-graphs), Rare Books, Maps and Music Collections

Read or download this book from our Digital Gallery.

Welcome to the latest of our new fortnightly series where we introduce you to some favourites from our collections for you to enjoy reading, all freely available online.

The latest choice is an unusual and at times entertaining example of an autobiography of a man of humble means who led an extraordinarily full life, often being led astray by the temptations of alcohol.

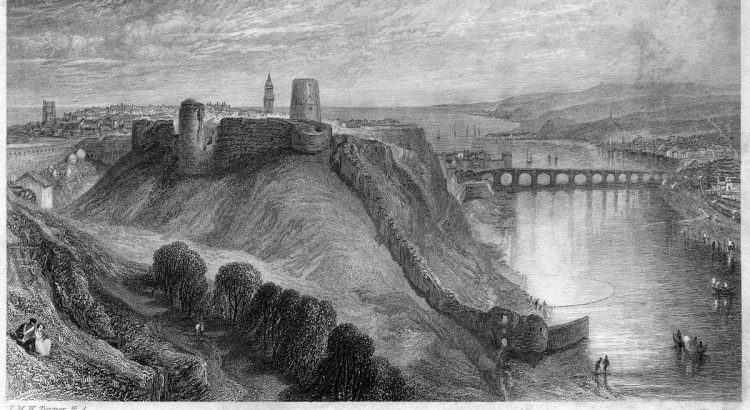

The town of Berwick-upon-Tweed is the most northerly one in England. Its strategic importance, as port and military stronghold on the border, led to it changing hands several times between Scotland and England in the Middle Ages, before it finally became part of England in 1482. However, the town has maintained close economic and cultural links with Scotland throughout the last 500 years. The National Library has actively collected early examples of Berwick printing, from the first examples, which appeared in the 1750s, onwards. One such Library acquisition back in 1980, was the Reminiscences of the life of Thomas Marshall of Berwick, written by Marshall himself and printed by Daniel Cameron of Berwick in 1835.

There are no other copies recorded in major UK libraries on JISC Library Hub, so presumably the book had a relatively small print run, its publication being funded by subscribers from the town (who are listed at the end of the book). It has now been digitally preserved as part of the Antiquarian Books of Scotland resource on our Digital Gallery.

At times his book reads like a picaresque romp through the late 18th and early 19th centuries, interspersed with anecdotes and digressions in which he shows a keen appreciation of local dialect, folk tales and poems. A literary masterpiece it most certainly is not, but it is well worth a read. Its readability rests on the fact that Marshall is an opinionated, well-read, and widely-travelled man who has seen things far beyond the ken of his fellow citizens of Berwick. Towards the end of his autobiography, Marshall, addressing some of these fellow citizens, notes:

I know some, whose circle of action never exceeded that of 12 or 14 miles in diameter, who have such amazingly circumscribed views of things, that almost any custom differing from their own affects their consciences. This is truly a diseased state of mind, and pitiable in the extreme. By travel the trammels of prejudice get shaken off; the soul becomes enlarged …

(p.233)

In his book he has realised that the “common sense part of his character would not be at all interesting to the public,” so he therefore concentrates on the frequent occasions where he has behaved recklessly, without thought for the consequences of his actions. He therefore leaves out much standard biographical information: we learn almost nothing about his background, his wife and family, or how he financed his medical education. He can be maddeningly allusive and vague in describing the reasons for his downfall, but alcohol has clearly played a large part in some of his many mistakes. Marshall is dismissive of “chatterers that I have heard in Abstinence Societies, who know no more about the matter than reading pamphlets.” For him alcohol has at times been a companion and a pick-me-up. Unfortunately for him, he has often succumbed to drinking to excess and at the end of the book he admits that he has “tried hundreds of times to get cured of this disorder by natural means, but without success.” Reminiscences, however, is remarkably free of self-pity; Marshall can be self-righteous but he makes no excuses for his conduct.

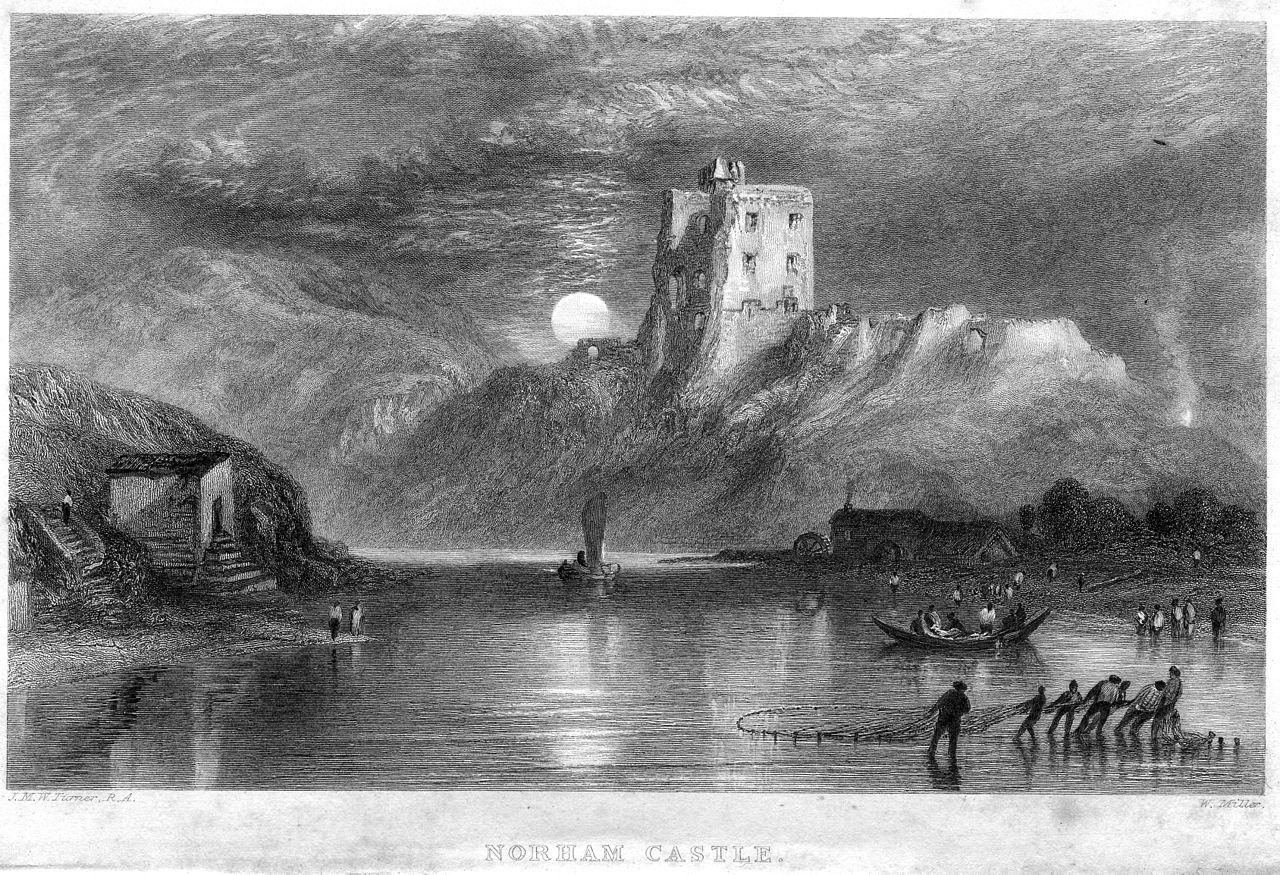

The book starts out as a conventional autobiography. Marshall was born in Horncliffe, a village a few miles west of Berwick on the banks of the River Tweed, in 1782. At some point in his early childhood, the family moved to another village on the banks of the Tweed, Norham. A few miles further west of Horncliffe, Norham was famous for its ruined medieval castle, as mentioned in Sir Walter Scott’s poem Marmion. The author hints at a difficult relationship with his father, a quick-tempered man who often lost patience with his son. However, salvation was at hand through his Aunt Hannah. She had no children of her own so was able to provide a refuge for young Thomas to escape his father’s wrath, as well as a plentiful store of fairy and ghost stories for her nephew.

Young Thomas did receive an education, in the Norham village school, and not just of the rudimentary kind of the labouring classes. He was clearly above average intelligence, as he describes learning Latin from an early age. Moreover, as the solitary pupil of the subject in the class, he could not help feeling “a little contempt for my English school-fellows”. His feelings of superiority led him to become “an insulated sort personage” who immersed himself in whatever books he could find. His childhood ended at the age of 15 when he was sent to be an apprentice to Mr Sanderson, a grocer in Berwick. A key moment in Marshall’s life occurred in his late teens when he saw a play, Isabella, or the fatal marriage, performed by some travelling players in Berwick. The sentimental drama made a powerful impression on the young man and brought him into conflict with the teachings of his local minister, Mr Blackhall, who was very anti-theatre. Marshall remembers a fearful internal struggle while saying his nightly prayers, with competing voices in his head in favour of theatre and religion, which he abruptly resolved by deciding on the spot in favour of theatre. He justifies his decision with some reasoning which seems very convoluted to the modern reader; while he remains a committed Christian, he displays in the book a deep scepticism for clergymen and organised religion as practised in Britain.

In 1801 Marshall left the employment of Sanderson the grocer and had a brief stay in London, where he worked as a shop assistant, before returning to the family home in Norham. The next stage in the author’s life sees him setting himself up in business as a grocer in Berwick. However, his educated mind and restless spirit chafed against a life of “insipid sameness” as a grocer and the “limits of a petty shop.” Filled with a desire to see the world, he became a packman (travelling salesman) for 2-3 years, peddling his wares all over south-east Scotland. Eventually he became tired of a life, which although full of incident, was “very far from being pleasant”. Marshall comments that hawkers were “in a great measure shut out from society; they are seldom treated as honest men, although many of them are really so.” A chance encounter with a group of travelling players leads to a brief spell as an actor, but the lack of job security and the petty rivalries of his fellow-actors were not for him, “I was in search of happiness, and that is not to be found among actors.”

Marshall’s next job was a gardener at the Duke of Northumberland’s residence at Alnwick Castle. While not finding the work disagreeable, some unspecified friends, presumably feeling that his talents were being wasted, made plans for him to study surgery so he could join the navy. Marshall chose to travel to London to study with the renowned anatomist Joshua Brookes (1761-1833). Money was seemingly no object despite Marshall’s peripatetic and not very well-remunerated life in the preceding years. Marshall subsequently passed the necessary exams to secure a posting as an assistant surgeon in the naval packet service with the promise of a posting to the West Indies. His optimism at the time was, however, soon tempered by the realisation that attitudes in the armed services were not always to the liking of the free-thinking and rather outspoken young man he had become,

there is a constant applauding of the powers that be, in every thing that they do or say; a constant abuse of any person who thinks differently from the rulers of the nation … and a firm confidence that all nations are in the wrong except England.

pp. 102-103

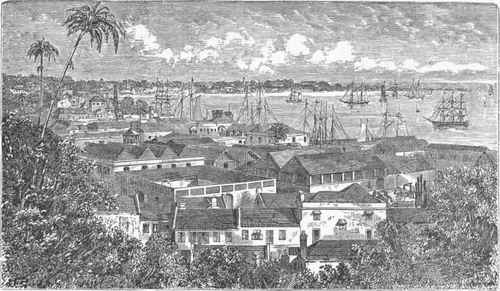

Marshall’s first landfall in the West Indies was the island of Barbados. He does not shy away from mentioning the presence of slaves and the unjustifiable nature of their existence, even if he does slip into something of the derogatory and racist language common in the period. Reminiscences was published shortly after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, but Marshall is still scathing about the so-called freedom of the former slaves and the generous compensation paid to former slave-owners for giving up their property.

As well as tours to the West Indies, Marshall also gets to see Nova Scotia, and New York, where he observes that there is “a rooted animosity to England and English government in the minds of the people; and in most points they thought themselves vastly superior.” Marshall finds these feelings of superiority unfounded, “I never saw vice in such strong forms as in the States.” A later voyage takes him to Madeira and Brazil, before he becomes directly involved in the Napoleonic Wars, witnessing Admiral Legge’s bombardment of the Spanish port of Cadiz in 1811. A further trip to South America showed him to be the hardened sailor, “I had now thrown off all dread of climate, or sea, or fever, or of any thing else.”

Marshall’s naval career is terminated by the end of the war in Spain between Britain and France in 1813. Once back in England he mentions that he is now a married man. He provides no details of when and where his marriage took place or his wife’s name, but parish marriage records for Cornwall reveal that Thomas Marshall, surgeon of HM Packet Diana, married an Eliza(beth) Sarvis on 29 April 1813 in St Just in Roseland, near Falmouth. He seems curiously untroubled about having to provide for his wife or his joining the ranks of the hundreds of other de-commissioned officers in need of employment. In fact, he decides to set off on foot from Plymouth to London with no clear plans, “I scarcely knew for what purpose.” He makes no mention of his wife accompanying him to London and his money soon runs out. Eventually begging and borrowing his way to London he manages to return to Berwick and secures a doctor’s practice in Melrose, where he stays for 18 months; however, he “had become a citizen of the world” and was dissatisfied with the lot of a country doctor. Another move ensued, this time to Newcastle, where in straitened circumstances he enlisted in the Durham militia at Barnard Castle. Marshall admits at this stage he was at a low ebb, “I was sunk and cared not much how I acted.”

After being sent to Glasgow, the militia was disbanded in 1816. Marshall had received a letter informing him of the chance of work as a ship’s surgeon in Falmouth in Cornwall. There followed another picaresque cross-country trek from Newcastle to Falmouth, with money once again in short-supply. Marshall managed to get into trouble with the local constabulary in Yorkshire after over-indulging in liquor with some travelling companions. He describes staying in a horrible doss house in Derby and being reduced to selling some of his clothes in Bristol and Exeter to get food and lodgings, before he eventually made it to Cornwall, exhausted and penniless. The promised post on the ship was secured, but a journey to the islands of Sicily and Malta ended with dramatic consequences. Marshall quarrelled with the captain in the presence of a high-ranking nobleman – the implication is that he was under the influence of alcohol – thus ending his career as a ship’s surgeon at a stroke, the slighted captain being “the cause of all my future misery and degradation.”

Marshall’s next choice of career was that of the “quack doctor”, travelling round with a medicine chest; but after wandering round Cornwall he realised that, as a qualified medical man, he lacked the selling techniques and brazenness of the real quack doctors, “in the art of money-making I was a downright novice.” At this point in the narrative his wife Eliza makes a sudden re-appearance, along with a child, as they both accompany him in another epic trek back up north to Berwick. Her whereabouts during the time since the time they were married are not mentioned, perhaps she stayed in Cornwall the whole time, but she now found herself sharing a life of semi-vagrancy with him and their child. An encounter with a feisty Scottish woman, Susy McDonald, in a doss house in Lichfield is described with gusto, in particular an incident where the elderly woman fights off the amorous attentions of a fellow-lodger.

Seemingly bored with a straight narrative of his wanderings, Marshall now abruptly switches from prose narrative into a dialogue between him and an anonymous and sarcastic critic who at one point comments, “I think your life has been little else than a scene of blunders!” In the course of the dialogue more of the journey up north is revealed, which includes a detour to Liverpool and an abandoned attempt to emigrate to America (there is no further mention of their child). He eventually ends up back in Berwick where he works as a mason’s labourer on the construction of Berwick pier, designed by the famous civil engineer John Rennie.

Labouring on the pier with the “uncultivated” was another low point for Marshall. Poor health caused him to give it up and to do a variety of jobs including schoolmaster and chapman, hawking chapbooks and broadsides. In Pigot & Co.’s trade directory for 1825-26 Marshall is also listed as a carrier in Berwick travelling up to Edinburgh on Tuesdays and returning on Fridays. In one particularly interesting passage in Reminiscences Marshall notes that the 1829 execution of the West Port murderer, William Burke, of Burke and Hare fame, was a particularly profitable occasion for “flying stationers” such as himself. In the course of a week he and a fellow chapman criss-crossed the whole of North Northumberland selling chapbooks on Burke.

The main narrative ends with allusions to time spent in Berwick jail, presumably for drunkenness. In a rather cryptic conclusion, he freely admits to moral failings and “mental blindness,” causing him to deviate from the straight and narrow, which, it is implied has been caused by a fondness for alcohol. The only medicine he can turn to seems to be to admit his failings and throw himself on God’s mercy,

I have applied to the Doctor, in his way, received his prescriptions, and used them with the most beneficial effects; but the moment I cease to use the medicine, that moment I become blind, and walk as crooked as ever. (p. 274)

He closes with an avowal of his determination to prevent lapsing into ‘blindness’ again.

Marshall seems to have devoted the rest of his life to temperance, albeit in his own idiosyncratic manner. He ventured into print once more in 1839 with a work, Aquarius, or the History of drunkenness, also printed by Cameron of Berwick. In a rambling discussion, over 300 pages long, he traces the history of mankind’s relationship with alcohol from the time of Noah onwards, writing from the viewpoint of someone with deep personal knowledge of the subject. The temperance movement in Britain had grown rapidly in the 1830s and whatever reservations Marshall expressed towards organised societies in Reminiscences, they appear to have disappeared by the time of Aquarius, as he now throws in his lot with the movement.

In the 1841 Census Marshall is recorded as a “temperance advocate” living with Eliza, and six children, the two eldest sons being recorded as printer’s apprentices. That same year a revised, second edition of his autobiography appeared, The life of Thomas Marshall, the Tweedside temperance advocate. The death of a Thomas Marshall in Berwick is recorded in 1844; the minutes of a meeting of the Board of Guardians on 21 May, charged with administering poor relief in Berwick, notes that funeral expenses were ordered for a Thomas Marshall of Tweedmouth (the part of the town south of the River Tweed) – life as a temperance advocate may have been spiritually rewarding but was probably not a lucrative one.

Look out in two weeks for our next Curator’s Favourite, and in the meantime enjoy reading!

Further information

Scottish chapbooks on temperance in the Library’s collections

English ballads on temperance in the Library’s Crawford collection