In order to build and promote the Library’s collections you need to have at least some familiarity with them which means doing a bit of reading. Sadly contrary to what some might think National Library of Scotland staff don’t spend their working days reading the collections, we have too many other things to do. So in my spare time during the lockdown I thought I would combine a bit of business with pleasure by reading some writers who are likely to be the focus of events and exhibitions when the Library reopens.

We are planning to do an exhibition on Scottish writers who published using pseudonyms next year and Alastair MacLean is one of them. MacLean published two thrillers “The Dark Crusader” (1961) and “The Satan Bug” (1962) using the pseudonym Ian Stuart in part to see if his books would succeed on their own merits without his name on the cover. It was largely a failure as the books sold a lot fewer copies than his earlier novels and were fairly quickly reissued as Alistair MacLean novels.

Success as a writer did not seem to sit well with MacLean perhaps because it initially came so easily. His first novel “HMS Ulysses” published in 1955 and based on MacLean’s wartime experiences on the Arctic convoys became the first hardback in Britain to sell 250,000 copies in six months and subsequent novels repeated this success at home and internationally. In 1963 shortly after his experiment with a pseudonym MacLean retired from writing to become a hotelier. His foray into running hotels was not a success and he returned to writing three years later no doubt to the great relief of his publishers as MacLean is almost certainly the most successful author born in Scotland in the last 100 years.

Although MacLean has worldwide sales of an astonishing 200 million copies which is more than John Grisham, C.S. Lewis or Ian Fleming and a bit less than J.R.R. Tolkien or Stephen King his books have largely disappeared from bookshops and bedside tables since his death in 1987. You are more likely to find his books in charity shops than bookshops and he has largely vanished from the culture apart from showing of films scripted by him or adapted from his works. If “Where Eagles Dare” the 1968 film starring Richard Burton and Clint Eastwood and with a screenplay by MacLean is not on television this week it is likely because it was shown last week. In the era of Lee Child are MacLean’s book still worth reading?

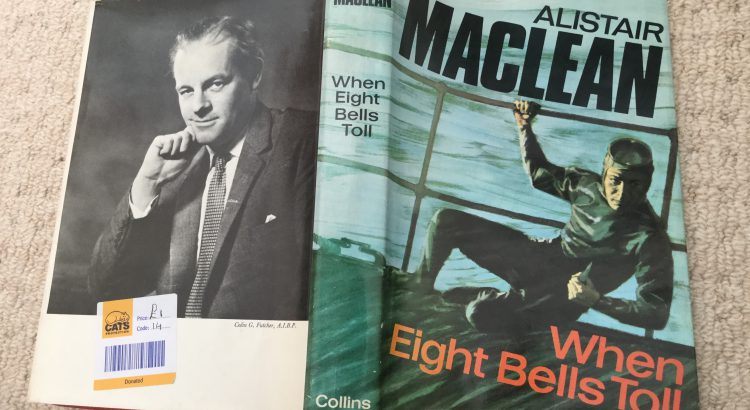

The only book I had to hand by MacLean during the lockdown was his 1966 comeback novel “When Eight Bells Toll”. I had bought this for £1 in a charity shop earlier this year partly as it had the original evocative dustjacket with an illustration of a scuba diver armed with a knife on the front and a photograph of a young and slightly rakish looking MacLean on the back. It charmingly is also inscribed “Christmas 1966. To Andrew from Bess with love”. As it was published in October 1966 and shot to the top of the bestsellers list Andrew would not have been alone in receiving it as a Christmas gift that year.

The novel starts with what reads like an essay on the history and destructive capabilities of the Colt 45 Peacemaker but we quickly learn that the narrator giving us this history lesson is staring down the barrel of a Colt 45 waiting for it to go off. In another twist we learn that the gun is in the hand of a dead man, a former colleague of the narrator. Our hero has quietly boarded a potentially hijacked ship and now has to evade the crew and make his escape. The breathless narrator explains his predicament as follows “I opened the outer door the way you’d open the door to a cellar you knew to be full of cobras and black widow spiders. The way you would open the door, that is: were cobras and black widows spider all I had to contend with aboard that ship, I’d have gone through that door without a second thought, they were harmless and almost lovable creatures compared to some specimens of homo sapiens that were loose on the decks of the freighter that night.” Against the odds and despite being nearly strangled to death our narrator manages to escape the boat and then avoids the many grenades thrown at him as he swims away.

This striking opening chapter has the feel of a pre-credit sequence from a James Bond film. You are thrust straight into the action and our as yet unnamed narrator is in constant peril with a new twist on every page. The James Bond comparison is apt as this is MacLean’s attempt at a spy novel and features the gadgets and spy craft that are familiar to us from Ian Fleming’s novels. Our hero overwhelms his opponent by pulling a dagger from a concealed pocket and in the next chapter returns to his own ship which has an array of gadgets. What appears to be a second engine is in fact a secret compartment that houses a powerful transmitter, 4.5 German Lilliput pistols, listening devices, house-breaking tools and knock out drops. The transmitter is used to contact his boss referred to as Uncle Arthur. Uncle Arthur uses code names for his wholly males agents, girls names that match the initial of their surnames. So in communications he is Annabelle and his agents are referred to as Caroline, Betty, Dorothy and Harriet. A typical exchange is “Betty and Dorothy aren’t coming home any more, Annabelle. Someone has to pay”. Which might not give much away to any eavesdropper but as the speakers are clearly male might raise a few suspicions.

Our hero who we learn is called Philip Calvert is quite a different character to Bond. A running trope is his annoyance at being called a secret agent by his boss and other characters. He regards himself as a humble civil servant who as part of his duties might be killed or have to kill others. He has been sent to the Highlands of Scotland to investigate the disappearance of a number of ships carrying valuable cargos, the latest stuffed with gold bullion. If a Scottish literature Top Trump card set existed MacLean would score high points for his sheer unmitigated Scottishness. Descended from the Clan MacLean he was a son of the manse born in Glasgow but brought up in Daviot near Inverness and spoke Gaelic as his first language. The novel’s setting on the rugged West Highland coast of Scotland allows MacLean to show his love and knowledge of both his native land and the sea.

In search of the pirates Calvert journeys along the coast in a helicopter meeting a Highland Lord in his island castle, a village constable and some Australian shark fishermen who help him in his mission. It emerges that a cabal of shady businessmen, Lords with Lloyds of London connections and suspicious heavies with European accents have been seizing and then sinking ships in a dangerous piece of coastal water called the Beul nan Uamh (Mouth of the grave) and then diving down to retrieve the valuable cargo. The pirates have kidnapped members of local families in order to get them to do their bidding and are holding them in the basement of the island castle. This leads to innumerable twists and turns as Calvert does not know who to trust and apparent allies turn our to be in league with the kidnappers and vice versa.

MacLean is king of the twist, what he is not quite so good at least in this novel is clear plotting. MacLean seems to realise this as quite late in the book he gets Calvert to explain the pirate’s plan to another character at some length. Perhaps he got distracted by the beautiful Highland coastal scenery or was a little rusty after his sabbatical in the hotel trade.

I can certainly recommend Alistair MacLean at least based on this book. It is almost a pure adventure novel and MacLean’s heroes are old fashioned gentlemen who show respect to everyone except obvious baddies so it has not really dated. MacLean perhaps as a legacy of his Presbyterian background saw no place for sex in his novels and women are largely marginal characters. MacLean’s lasting legacy is probably as an influence as alongside other authors such as Hammond Innes he created the modern adventure novel. Ian Rankin has said that one of the reasons he decided to write genre fiction was because his father read Alistair MacLean and he wanted to write something he would read. Lee Child’s hero Jack Reacher, quietly masculine, polite, reliable, practical but always ready to step up if required has much in common with MacLean’s heroes.

MacLean’s books might have disappeared because he never quite managed to produce an iconic classic like Frederick Forsyth’s “The Day of the Jackal” or Jack Higgin’s “The Eagle Has Landed” that would act as an entry point to his work. However without his work to draw on these books and the whole genre of the modern British thriller might not exist.