It shocks many people to learn that when in 1833, the British Parliament finally abolished slavery in various parts of the British Empire, those most closely involved in the trade received huge sums of money in compensation. It has been estimated that of the £20 million compensation payments, half remained in Great Britain, with the British taxpayer effectively remunerating a group of people and institutions who in many cases had already accumulated significant wealth through slavery. These people were often of high social standing in the aristocracy and gentry, as well as in parts of the middle classes, and they were also geographically dispersed, not just focused on the traditional slaving ports such as London, Bristol, Liverpool, and Glasgow.

£20 million in the 1830s was around 40% of government annual expenditure, and as a share of Gross Domestic Product, worth the equivalent of around £80 billion today, so the significance of this capital transfer should not be underestimated.

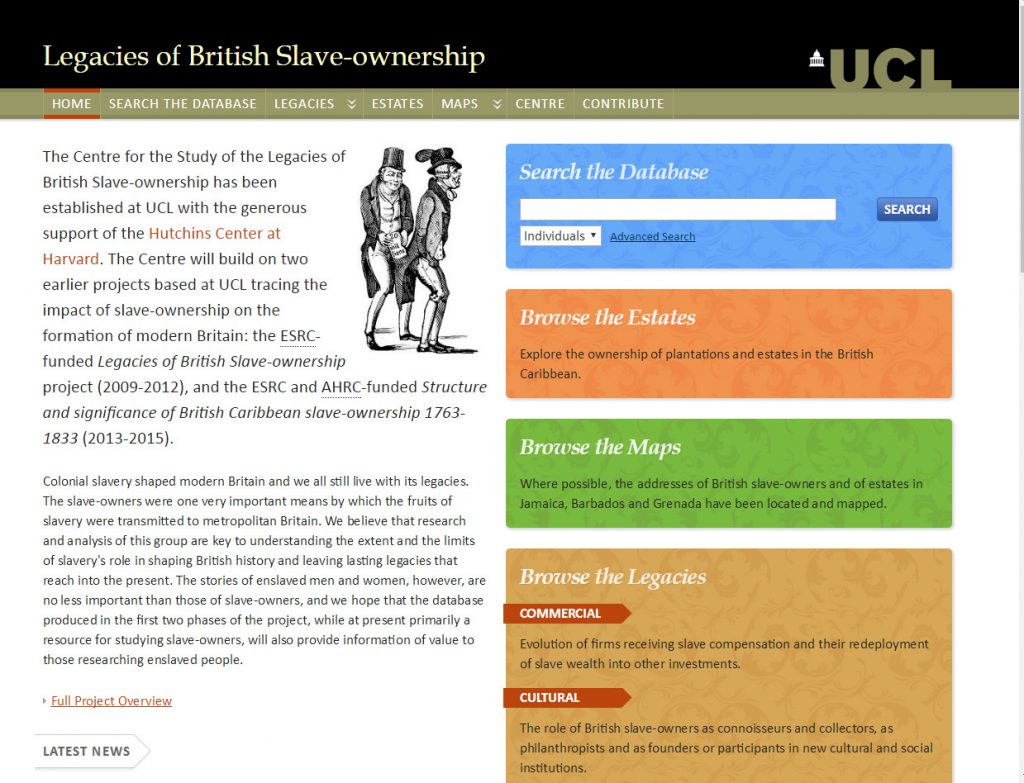

The Legacies of British Slave-ownership project at University College London has been leading the way in researching this subject in recent years. The initial focus of the project from 2009 was to index the records of the Slave Compensation Commission, set up to manage the distribution of the £20 million compensation, thereby creating a relatively complete census of slave-ownership in the British Empire in the 1830s. The project has then gone on to document all the slave plantation estates in the British Caribbean in the period from 1763 to 1833, as well as all the slave-owners and related financial beneficiaries for these estates too.

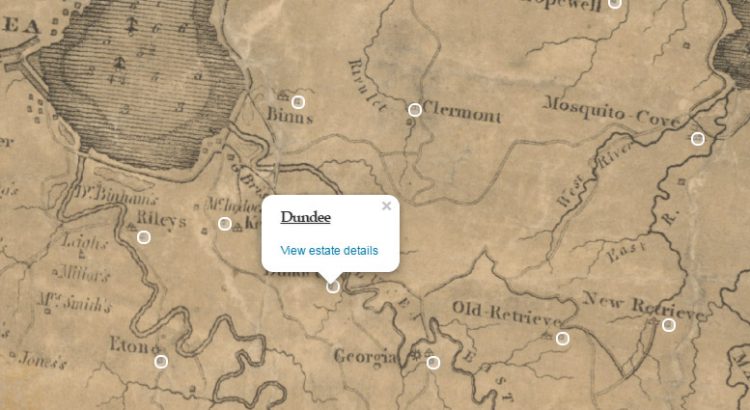

In September, the LBS Project unveiled a new map-based way of searching and viewing these records – both the plantation estates, as well as the geographic distributions of those receiving compensation for their slaves. Although this is still work-in-progress, it already provides a powerful and useful way of visualising slavery information – as illustrated below.

The Library has also been pleased to assist part of this work in a small way through providing georeferenced maps of Jamaica and Scotland in the early 19th century, thereby allowing the location of places mentioned in the records to be more accurately positioned. James Robertson’s maps of Jamaica, surveyed in 1796-99, were the most detailed maps of the island surveyed during the period of slavery, and they show the location and distribution of 830 sugar estates. The LBS Project has now created a clickable overlay of these estates linking them to the records in their database. It is also possible to search the estates themselves and view the resulting records on Robertson’s maps. Much of this has involved detailed work from different sources, and further research is underway to link cattle-pens and smaller estate plantations. (Cattle powered the machinery in sugar mills and their dung was vital as fertiliser for growing sugar cane too).

Robertson’s mapping of Jamaica is also in itself an illustration of other linkages between Scotland and Caribbean slavery. James Robertson (1753-1829) (pictured left, courtesy of Shetland Archives) was born on the island of Yell in the north of Shetland, but emigrated to Jamaica in 1778 where he worked as a land surveyor and proprietor of a cattle pen. The Jamaican House of Assembly paid him a handsome £10,450 for his maps of Jamaica, and on his return to Britain in 1804, he was able to live off this bounty for many years. Robertson has been recently researched by Joanne Wishart of Shetland Archives, but he was only one of many Scots who travelled to the Caribbean with the hope of making serious money there from the plantation economy. It is estimated that Scots made up one third of the Europeans in Jamaica in the late 18th century.

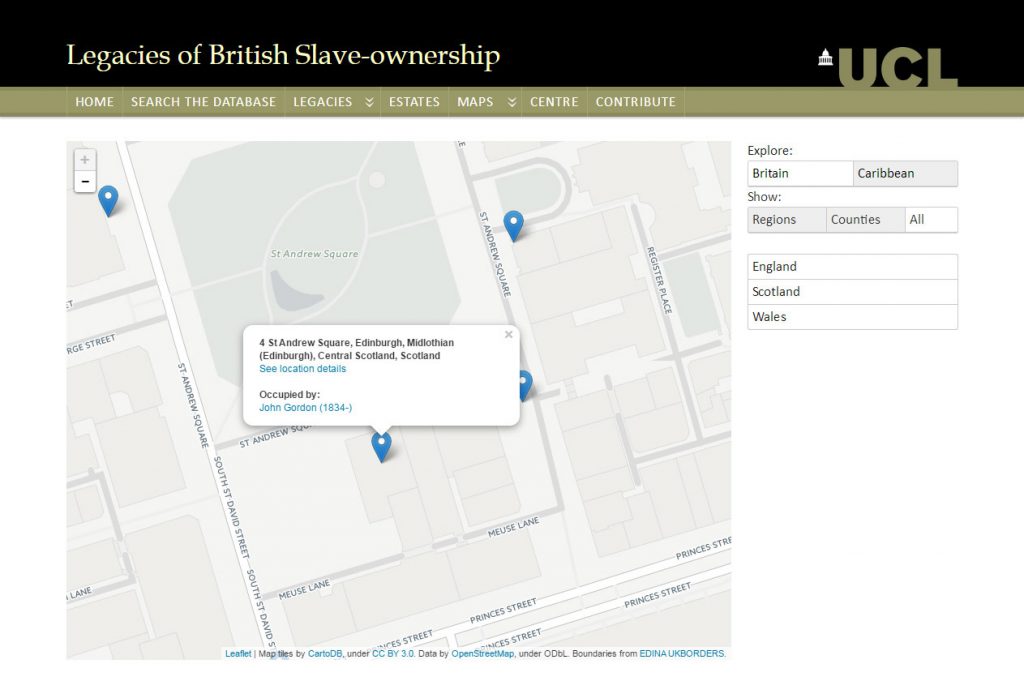

The new LBS map interfaces also show the geographic distributions of the beneficiaries of slavery and compensation claims back in Great Britain and Scotland. Although the geolocation of these addresses is not complete – there are currently 3,496 addresses in the LBS database, linked to 3,520 individuals, and 2,485 of these addresses have been located on the British map so far – they confirm that there were significant disparities in the distributions over the country. Scotland had a disproportionately high concentration of beneficiaries, and these were geographically concentrated too – particularly in Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Just by zooming in on two pins on the map in St Andrews Square give a flavour of the value of these records too at an individual level. John Gordon of Cluny at 4 St Andrew Square also owned property in London as well as Cluny Castle in Aberdeenshire, and was awarded £24,964 in compensation for his estates in Tobago. Cluny went on to acquire the islands of Benbecula, South Uist and Barra, and was chiefly responsible for major enforced emigration of many of the inhabitants to Canada in the 1850s.

James Auchinleck Cheyne (1795-1853) of Oxendean and Kilmaron, was a Scottish Writer to the Signet and accountant, living at 21 South St Andrew Street, who received over £3,000 for his estates also in Tobago. Cheyne was one of the original directors of the National Bank of Scotland in 1825 and Manager of the Life Insurance Company of Scotland in 1832.

Slavery is often an uncomfortable subject, whether in the past or the present, but the LBS Project has done a valuable service in gathering and presenting these records, so allowing a fuller understanding of the significance of slavery – personally, economically, and politically – in Britain’s history.

Other related links: