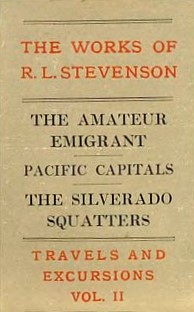

The choice: Robert Louis Stevenson – The Amateur Emigrant (Edinburgh, 1895)

Chosen by: Anette Hagan, Rare Books Curator (Early Printed Collections to 1700)

Read or download this book from our Digital Gallery.

Welcome to the latest of our new fortnightly series where we introduce you to some favourites from our collections for you to enjoy reading, all freely available online.

This week’s choice is a travelogue: Robert Loius Stevenson’s account of his impromptu trip to the US at the age of 28, his harrowing voyage from Glasgow to New York and the excruciating train journey to San Francisco.

To say it straight out: this isn’t an entertaining tale of thrilling adventures crossing the Atlantic and of glorious vistas of mountains and prairies from the train – really quite the opposite. Stevenson gives us a fascinating insight into the hardships of travelling on a shoestring in ill health, into his social conscience, his view on British mentality and emigration, and his impressions of life on the US frontier.

The eagle-eyed will have noticed that this travelogue was published posthumously, a year after Stevenson’s death in 1894. His literary editor, Sidney Colvin, held back the publication of the manuscripts for some 15 years. What you can’t see from the digitised version is that it doesn’t contain the complete account of the journey: Colvin not only sat on it, he omitted some 10,000 words of the manuscript before publishing it.

But first to the meat of “The Amateur Emigrant”.

It is 1876. Stevenson is in Fountainebleau near Paris where he meets the American magazine author Fanny Osbourne. Ten years his senior, Fanny has two children and also a husband in the US. Stevenson falls in love with her. Two years later, Fanny returns to the States and leaves behind a lovesick, lonely Stevenson whose only prospect is an ill-paid literary career. He is at a life-changing crisis point. What can he do? He decides to follow Fanny, hoping that she has started divorce proceedings. His friends try to dissuade him – in vain – and his parents aren’t even told of his plan. On 7 August 1879 he sets sail from Greenock on the Anchor Line steamer ‘Devonia’.

Stevenson, hard of cash and not in good health, travels second class. This is one down from cabin passengers but one up from steerage, though the two are not much different, as he sardonically points out: the second class passengers have a choice between tea and coffee but “the two were so surprisingly alike … by the palate I could distinguish a smack of snuff in the former from a flavour of boiling and dish-cloths in the second.” What he does have in second class, though, is a table: this is necessary because from the start he intends to publish his travel experiences, not least to pay for the trip, and he needs a place to write on board.

The social distinction between the two classes of passengers is curtly summed up: in steerage there are males and females, in second class gentlemen and ladies. Stevenson is a keen observer of the social nuances played out on the emigrant ship. The steerage passengers form ” a company of the rejected; the drunken, the incompetent, the weak, the prodigal, all who had been unable to prevail against the circumstances in the one land were now fleeing pitifully to another”. This is the second wave of emigrants: people who have left their homes not so much to create a new life, but to escape from their dire economic conditions. Allow me another poignant quote: the ‘Devonia’ was “a shipful of failure, the broken men of England.” Stevenson doesn’t hold back with his criticism; he is more concerned about the continued prosperity of many “unworthy capitalists” than about the poverty of some tipplers.

Stevenson draws some lively portraits and character sketches not only of official passengers, but also of a couple of stowaways. His vivid descriptions of the cramped and dirty spaces, the filthy passengers who won’t be seen washing themselves, the incessant noises and offensive smells in steerage invite sympathy rather than disgust in the reader: Stevenson’s tendency to identify with his fellow passengers lends a voice to the voiceless poor. For the author himself, the horrendous conditions mean that whenever possible, he sleeps on deck in order to breathe more freely. After a ten-day voyage the ship finally docks in New York. Stevenson’s ill health gets worse: rain lashes down throughout the night, which he spends walking outside after he just manages to escape an assault on his life in his hotel room. After his nightmare wanderings, he is so wet that he leaves behind his trousers, socks and shoes because no fire could have dried them before he and his fellow emigrants are finally herded on to the first train west.

Stevenson’s account of the rail journey across the plains and the Rocky Mountains is different from that of his sea voyage. Hardly any names are mentioned and there are no sustained descriptions of relationships. Given the constant change of train passengers, this is not surprising. But the real reason is probably his own sickness. Early on in the journey to Council Bluffs in Iowa he actually admits this much: “I had neither hope nor fear, and all the activities of my nature had become tributary to one massive sensation of discomfort.” Still, he writes down his impressions, which at first are favourable. Ohio for instance, although flat like Holland, is anything but dull, and even the great plains of Indiana, Illinois and Iowa are rich and various. In Chicago, he weakens again: “my consciousness dwindled within me to a mere pin’s head, like a taper on a foggy night.”

After several train changes, Stevenson embarks on the Pacific Railroad. Completeded only ten years earlier, this first transcontinental railroad will take him from Iowa all the way to San Francisco. Now the carriages are a little more comfortable and spacious, and at various stations in the middle of nowhere, settlers bring the travellers food. But the landscape! Nebraska’s plains remind him depressingly of the sea: “It was a world almost without feature; an empty sky, and empty earth; front and back, the line of railway stretched from horizon to horizon, like a cue across a billiard-board”. Some dots beside the tracks in the distance turn into a few wooden cabins, then disappear again. Of course, many towns have only recently appeared on the map as a result of the railroad, literally in the middle of nowhere. The contrast between the vastness of the country and the isolated signs of humanity is stark.

Stevenson is now looking forward to the change of scenery the Rocky Mountains promise, but once in Wyoming, he is again sorely disappointed: “Hour after hour it was the same unhomely and unkindly world … not a tree, not a patch of sward, not one shapely or commanding mountain form; sage-brush, eternal sage-brush”. No doubt this unfavourable impression owes something to Stevenson’s ill health. Some very insightful observations about his fellow passengers – the carriages were segregated to accommodate Chinese people in the first section, bachelors in the next and women with children in the last – and their attitudes to each other conclude his observations before the glorious descent of several thousand feet past old mining towns to the shores of the Atlantic and the Golden Gate. Stevenson’s relief is palpable: “Every spire of pine along the hill-top, every trouty pool along that mountain river, was more dear to me than a blood relation.”

Well! A pessimistic tone runs through this travelogue, no doubt about that. But it’s eminently readable and I’ve thoroughly enjoyed a different Stevenson voice from that of the adventure tales: a highly observant and critical traveller into the land of the free, on a desperate mission which we now know about, but which the narrator does not even touch on. The author remains incognito throughout.

Stevenson sent the first part. ‘From the Clyde to Santy Hook’ to his literary agent Sidney Colvin in London in December 1789 from San Francisco. Part two, ‘Across the Plains’, was sent the following year. Why Colvin did not arrange for their publication until after Stevenson’s death, and why he omitted whole paragraphs of his manuscript, is a story for another day. But I got so inspired by the travelogue that I’m now reading a Stevenson biography to find out more!

Look out in two weeks for our next Curator’s Favourite, and in the meantime enjoy reading!

Read more of Stevenson’s text online on our Digital Gallery.