The choice: Philip Doddridge, Some Remarkable Passages in the Life of the Honourable Col. James Gardiner. (London, 1748).

Chosen by: Robert Betteridge, Rare Books Curator (Eighteenth-Century Printed Collections)

Read or download this book from our Digital Gallery.

Welcome to the latest of our new fortnightly series where we introduce you to some favourites from our collections for you to enjoy reading, all freely available online.

This week’s choice made a household name of a Scottish soldier who died following the Battle of Prestonpans.

This week in 1745, 21 September to be exact, witnessed the Battle of Prestonpans, which gave the Jacobites control of the capital (with the exception of Edinburgh Castle) and allowed Charles Edward Stuart to set up court at Holyrood. The battle is famous for the Jacobite rout of the Government troops under General Sir John Cope and his army’s ignominious flight from the battlefield in the face of a Highland charge. One of the most senior of the Government soldiers to fall in the battle was Colonel James Gardiner who may have only been remembered in the years to come by military historians if it were not for a remarkable religious experience earlier in his life, and his friendship with one of the 18th century’s leading evangelical writers, Philip Doddridge (1702-1751), who would compose an account of Gardiner’s life.

Gardiner was baptised at Carriden, near Bo’ness, on 10 January 1686 and was educated at Linlithgow grammar school. Like his father he became a soldier and during the War of the Spanish Succession fought at the battle of Ramillies, where he was badly wounded. His remarkable escape and recovery make for one of the most striking episodes in the book. Doddridge first met Gardiner at Leicester on 13 June 1739, recalling that ‘I cannot recollect, I was ever equally edified by any conversation I remember to have enjoyed.’ Gardiner too was delighted to meet with Doddridge, having read many of his sermons, and they continued their friendship until Gardiner’s death. Their meeting was approximately 20 years after the key moment in Gardiner’s life, when a vision of Jesus saw him reject his former, wayward existence and embrace Christianity.

As well as honouring the memory of his friend, Doddridge’s aim in writing the work was to inspire ‘a lively sense of religion’ in his readers, using examples of Gardiner’s piety as an inspiration to others to lead a more Christian life. He also had to address what doubtful readers may have seen as excessive enthusiasm in Gardiner’s character, whilst persuading devout readers that religious rapture must have a rational basis. In recounting Gardiner’s life Doddridge makes much of the opportunities for vice open to soldiers and gives us an impression of Gardiner’s boisterous childhood by recording that ‘this lively youth fought three duels before he attained to the stature of a man’. In one of these, at only age 8, he received a scar from an older boy. Gardiner is depicted as having no religious inclination despite a number of lucky escapes that many of his contemporaries would have put down to divine intervention. There is a clear division between Gardiner’s dissolute and debauched, though apparently not drunken, life before his conversion and his shame at such self-indulgence afterwards. Despite such a dramatic change of heart Gardiner appears, according to Doddridge, not to have been overbearing in his conduct to others, notably his military colleagues, but rather inspired many of his men to more abstemious lives.

The progress of Gardiner’s military career was slow and can be put down to a lack of influential friends, although Doddridge, quoting one of Gardiner’s letters from 1743, records that he himself was quite easy about it. ‘The disappointment of a Regiment is nothing to me; for I am satisfied, that had it been for God’s glory, I should have had it; and I should have had been sorry to have had it on any other terms.’. He did however make a successful marriage in 1726 to Lady Frances Erskine, daughter of the 9th Earl of Buchan. His role as aide-de-camp to John Dalrymple, 2nd Earl of Stair took him to Paris in 1719 and it was here that he had the vision that would change his life.

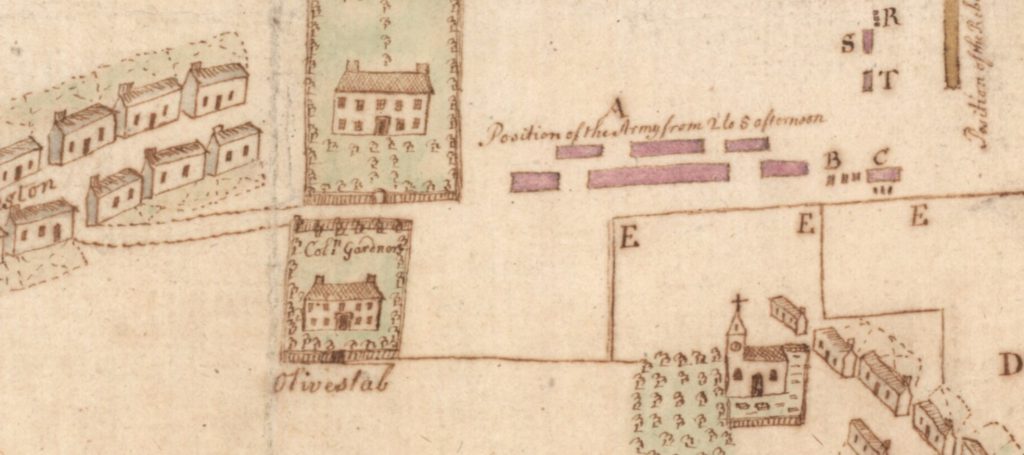

By the time of the Battle of Prestonpans Gardiner was in his late fifties and in poor health. By chance the battle took place within view of Bankton House which he had purchased in 1733 and Gardiner’s local knowledge helped General Cope to select a position with marshland in front which the Jacobites would have found ruinous to attack had they not been shown a way through under cover of darkness by a local farmer’s son. Cope’s supposed incompetence entered the popular consciousness but he was not himself to blame for the defeat, being let down by many of his inexperienced and undisciplined men. The dragoons under Gardiner’s command fled the battle and he was struck down trying to rally some retreating foot soldiers. Following the battle the mortally wounded Gardiner was taken to the church at Tranent where he died the following day. His horse survived the battle and became the mount of Prince Charles.

Doddridge wrote Gardiner’s life based on conversations with the man himself and correspondence, much of it lucky to have survived the ransacking of Bankton House following the battle, which was lent to him to complete the work. Gardiner’s heroic death received wide acclaim at the time but it is Doddridge’s account which kept his memory alive in the following years. There were 40 editions printed in the 18th century alone across the British Isles and as far away as Boston and Philadelphia and the work was regularly in print until 1864. Gardiner also appears in another publishing phenomenon: Walter Scott’s Waverley, as commander of the eponymous hero’s regiment. Though only referred to as ‘Colonel G—’ it is clearly Gardiner who Scott describes as one about who ‘strange stories were circulated about his sudden conversion from doubt, if not infidelity, to a serious and even enthusiastic turn of mind.’. Gardiner’s life is also commemorated by a monument, paid for by public subscription and erected in the grounds of Bankton House in 1853.

Look out in two weeks for our next Curator’s Favourite, and in the meantime enjoy reading!