During Doors Open Day, we try to take visitors to hitherto unknown parts of the National Library building at George IV Bridge. ‘The Void’ is the final destination of our tours on Doors Open Day – but what is ‘The Void’?

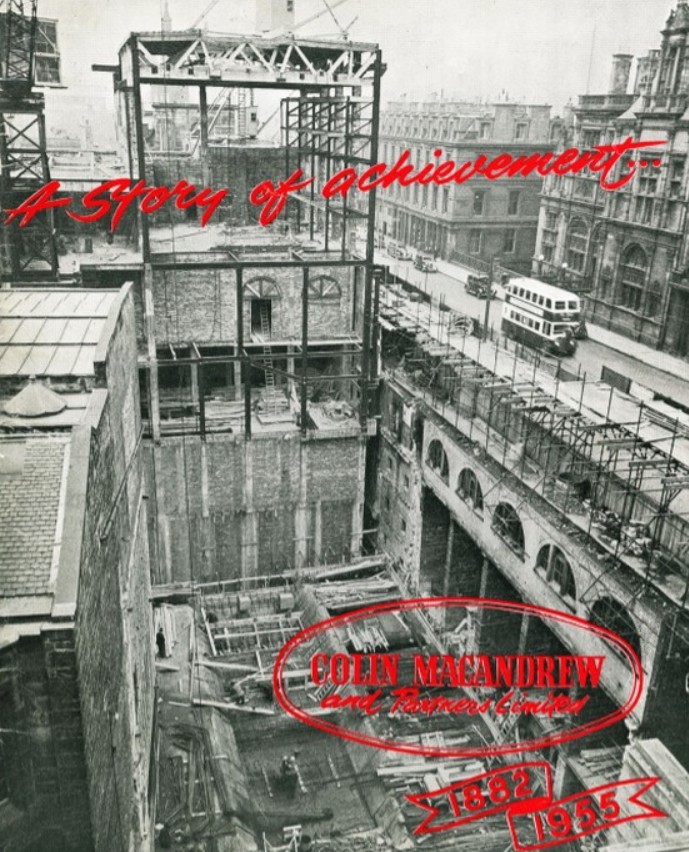

‘The Void’ is effectively a sub-street space between the structures of the Library building and of George IV Bridge itself. To get there, you have to find a door hidden on one of the stack floors, deep within the bowels of the Library. Within ‘The Void’, you can see the brickwork of the Library’s lower levels; the underside of George IV Bridge; and the stonework of the bridge’s structure which was built in the 1830s. This commemorative history of Colin MacAndrew & Partners – the main contractors during the Library’s construction – lets you see where ‘The Void’ is in relation to the Library:

‘The Void’ is the gap you can see between the Library structure and the Bridge in this image. As you cross the threshold into the Library, ‘The Void’ lies several floors below you. The Library utilizes some of ‘The Void’ and the area just behind the MacAndrew logo in the image above is where three huge water tanks for the Library’s sprinkler system are stored.

Although not a preserved street like Mary Stair’s Close, this nevertheless offers us a glimpse of the Edinburgh of centuries ago.

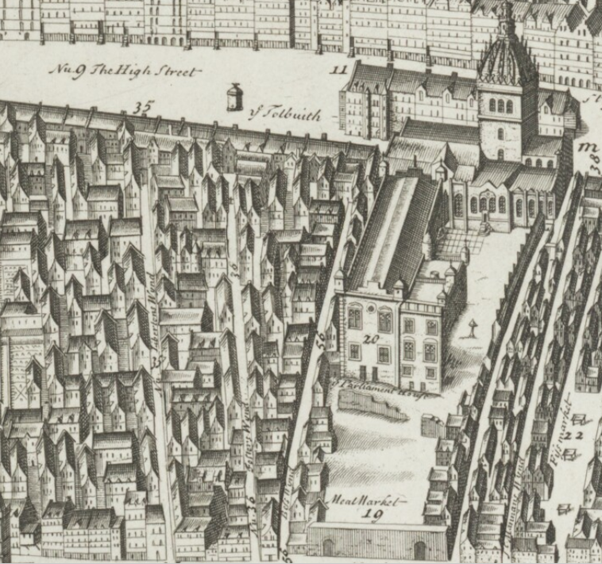

There are several maps and accounts of the Old Town in the Library’s collections which help us build an atmospheric picture of the neighbourhood on which both George IV Bridge and the Library now stand and what was there before ‘The Void’.

Following the success of the New Town, Edinburgh’s City Fathers sought to make further improvements to the rest of the city; one of these schemes would ultimately signal the demise of much of the Old Town’s neighbourhoods. If you wanted to get to the High Street from the south, you had to walk up steep, narrow wynds and closes on the northern face of the Cowgate Valley. George IV Bridge was built on the recommendation of the 1827 Edinburgh Improvement Act, which recommended that “a communication should be made from the Lawnmarket opposite the south end of Bank Street, to the Country on the South, by a New Street and Bridge over the Cowgate towards Bristo Port…”.

The proposed Bridge would span the Cowgate Valley, making it easier to travel into the heart of the bustling city. It was designed by the Edinburgh Architect Thomas Hamilton, who was architect to the Commissioners for the 1827 Improvement Act. Named after the late regent who had famously visited Edinburgh in 1822, the foundation stone of George IV Bridge was laid on 15th August 1827 but, due to problems with the necessary finances which ultimately led Hamilton to resign from the project, the principal construction took place over several years, between 1829 to1834. George IV Bridge was built up on both sides as an elevated street over ten spans which vary from 29 ft to 34 ft and are constructed of masonry with semi-circular arches – these arches are now mainly hidden except for those over Merchant Street and the large open arch over the Cowgate.

Several streets had to be demolished to may way for the new bridge, including Libberton’s Wynd – on which the eastern side of George IV Bridge, including the Library, now stands.

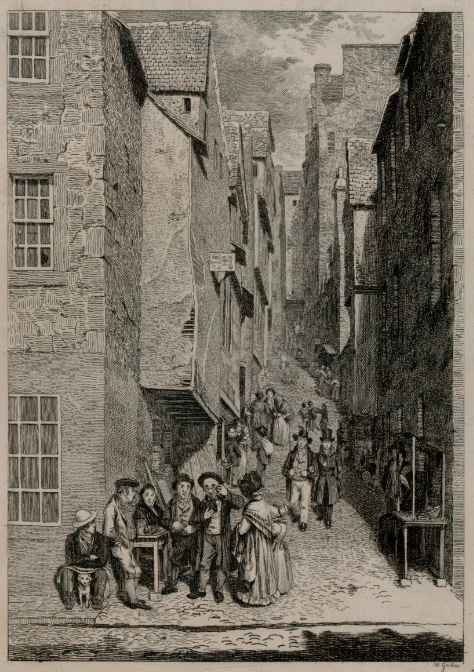

Libberton’s Wynd was described as being “broader than a Close, had the fronts of its stone mansions so added to and encumbered by quaint projecting out-shot Doric gables of timber, that they nearly met overhead, excluding the narrow strip of sky, and save at noon, all trace of sunshine”.

It was said to be risky to travel up the Wynd between 10 and 11 o’clock at night as one’s passage and garments were “endangered by certain domestic proceedings”. The surrounding tall tenements were densely populated – with several families living on each floor – and so before they went to bed they would empty the contents of their slop buckets and latrines out the window with a cry of “Gardyloo!” Given that the “fire from the windows was exceedingly brisk” not even a warning of “Haud yer haun!” would save you if you were unfortunate enough to be standing in the street below!

The Wynd was well known to the citizens of Edinburgh for at its head, where it joined the Lawnmarket, was the site of the city’s gallows – today you can see a trio of Brass markers in the pavement at the north end of George IV Bridge which indicate the site of gallows. Viewed as a form of morbid entertainment, the many executions which took place here were often attended by crowds several thousand strong, with perhaps the most infamous being that of the body-snatcher and murderer William Burke on 28th January, 1829.

Libberton’s Wynd was, however, also famed for housing one of the city’s best-known hostelries, known to be “the resort of all the revelling wits of the Toon”. Taverns were once key features of Edinburgh’s Old Town communities, whose patrons often came from various social classes. In his Traditions of Edinburgh, Robert Chambers recalled that:

“Tavern dissipation, now so rare amongst the respectable classes of the community, formerly prevailed in Edinburgh to an incredible extent, and engrossed the leisure hours of all professional men, scarcely excepting even the most stern and dignified. No rank, class, or profession, indeed, formed an exception to this rule. Nothing was so common in the morning as to meet men of high rank and official dignity reeling home from a Close in the High Street, where they had spent the night in drinking. Nor was it unusual to find two or three of his Majesty’s most honourable Lords of Council and Session mounting the bench in the forenoon in a crapulous state.”

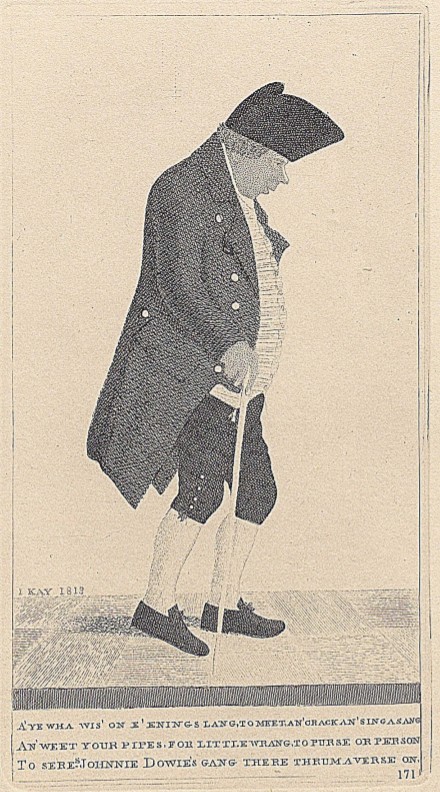

Included in John Kay’s famous Series of Original Portraits and Caricature Etchings is a picture of a Mr. John Dowie, Vintner, who owned a tavern in Libberton Wynd. Known to be “the sleekest and kindest of landlords”, Dowie always wore “a cocked hat, buckles at the knees and shoes, as well as a cross-handled cane, over which he stooped in his gait”.

Previously ‘The Mermaid’, Johnnie Dowie’s Tavern was a “place of old standing and particularly celebrated for the excellence of its ale, Nor’ Loch trout, and Welsh rarebit”. Despite its grand title, Dowie’s ‘Nor’ Loch Trout’ is believed to have been a fanciful title for Whiting fried in breadcrumbs and butter – I’m not sure you would have wanted to eat any Trout from the Nor’ Loch! Though the food may have been popular, Dowie’s Tavern was renowned for its drink:

A’ ye wha wis’ on e’enings lang,

to meet, an’ crack, an’ sing a sang,

An’ weet your pipes, for little wrang.

To purse or person,

To sere * Johnnie Dowie’s gang,

There thrum a verse on.

O Dowie’s Ale ! thou art the thing

That gars us crack, an’ gars us sing,

Cast by our cares, our wants a’ fling

Frae us wi’ anger;

Thou e’en mak’st passion tak’ the wing,

Or thou wilt hang ‘er.

This was part of a humorous poem which was published as a Broadside in September 1789 – you can view it in full @ https://digital.nls.uk/broadsides/view/?id=15989.

His most popular drink was the Edinburgh Ale brewed and supplied by Mr Archibald Younger, “a potent fluid which almost glued the lips of the drinker together, and of which few, therefore, could dispatch more than a bottle”.

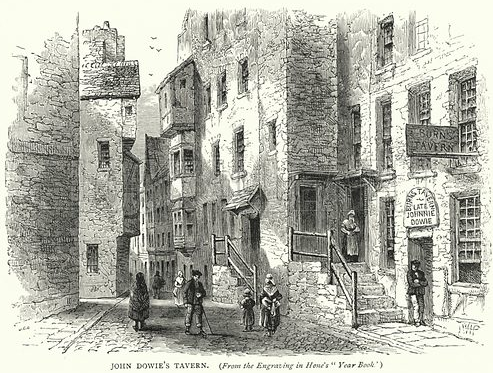

Dowie’s was “as dark and plain an old-fashioned house as any drunken lawyer could have wished to settle in”. Descriptions of the tavern give an impression of the claustrophobic confines of the old town. Occupying the ground floor of a tall tenement, “the principal room, which looked to the Wynd was capable of containing about fourteen persons, but all the others were so small, that not above six could be stowed into each, and so dingy and dark that, even in broad day, they had to be lighted up by artificial means”.

The Tavern was a house of “much respectability” and the majority of its customers were social rather than intemperate in their enjoyments. It was a popular meeting place for “the chief wits and men of letters” in Edinburgh as it “afforded a convenient resort for those who took ‘meridians’ (mid-day drams) and at night strong ale drinkers found it the very focus of excellent cheer and good company”.

As such, it was regularly frequented by writers, artists and many members of the judiciary – Dowie’s patrons are believed to have included the poet Robert Fergusson; David Herd, collector of Scottish Songs and Music; George Paton, a noted antiquary; David Hunter of Blackness; Anthony Woodhead, solicitor-at-law; George Martin, Writer-to-the-Signet; while Christopher North (a.k.a. John Wilson) of Blackwood’s Magazine and the poet Thomas Campbell were known to meet in this “couthy mansion”. One group of famed patrons – whose number included the brewer Archibald Younger, Edinburgh’s City-Clerk John Grey, and John Buchan, a Wrtier-to-the-Signet – took the nickname, “The College of Dowie” (which was possibly a play-on-words of the then Scots seminary at Douai in northern France). Dowie’s Tavern was also widely believed to be the favourite drinking den of Robert Burns during his sojourn in Edinburgh in 1786. According to John Kay, Burns, alongwith William Nicol and Allan Masterton, the classics and writing masters at Edinburgh’s High School – “the Willie and Allan of Burns’ well-known Bacchanalian song, Willie Brew’d a Peck o’ Maut” – held “many a social meeting” at Dowie’s. The smallest of the Tavern’s windowless chambers was an irregular oblong box which was commonly referred to as ‘the Coffin’, and was believed to be Burns’ favored seat in the tavern.

Following John Dowie’s retirement, the new owners would use the association with Burns to great effect. In July 1821, William MacPherson – “late Messman to the Officers of the Royal Lanarkshire Militia” – placed a notice in The Caledonian Mercury newspaper announcing that he had re-opened Dowie’s as Burns’ Tavern, but also that it was “his anxious wish to conduct the house in the same style that formerly gave so much satisfaction”; and that it had “recently undergone a complete repair, been respectfully furnished, and lighted with gas, and now contains a room in the upper tier, large enough to accommodate more than twenty gentlemen at dinner”. With regards Burns’ favourite seat, the notice added that “the favored apartment of Burns, termed ‘The Coffin’, and long an object of curiosity to strangers, has been preserved in its original state; and the humorous poem, addressed to Johnnie Dowie, dated 14th September 1789 is still to be seen in the house and in the hand-writing of the Poet”.

With the new owners installing gas lighting and dressing it with green cloth, ‘The Coffin’ became something of an attraction to visiting patrons and a draw for those wishing to honour the Bard. For example, on 3rd February 1825, The Fife Herald reported that a number of gentlemen had celebrated Burns’ birthday by gathering for their annual entertainment in Libberton’s Wynd, Edinburgh, “long and better-known under the designation of ‘Johnnie Dowie’s’” and that “during the evening many toasts and sentiments connected with the occasion were given from the Chair. Some of the Poet’s finest songs were sung in true Scottish style, and the meeting was fully inspired with the remembrance that the Bard himself, under the same roof, many years ago, had spent some of the most convivial moments of his life.”

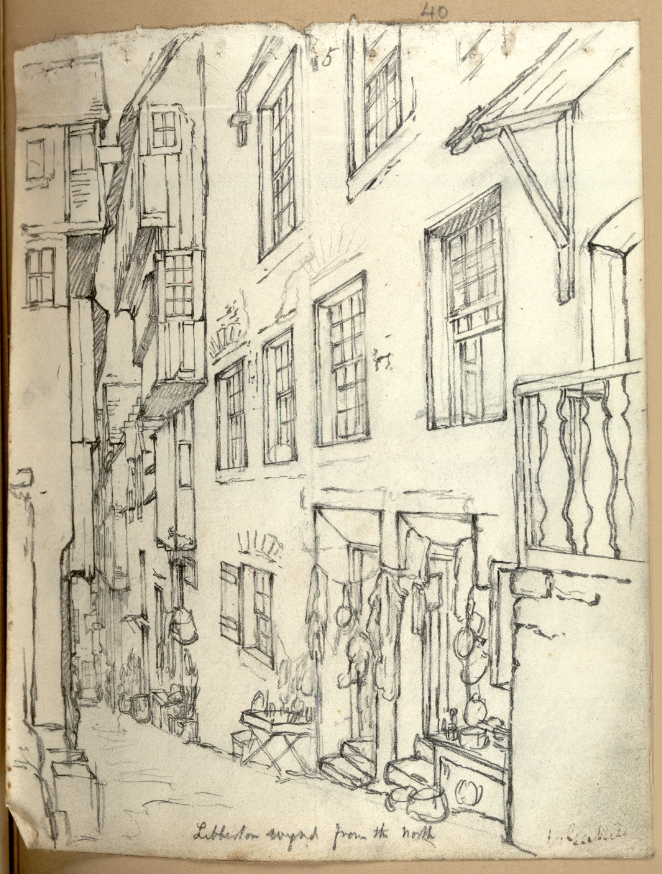

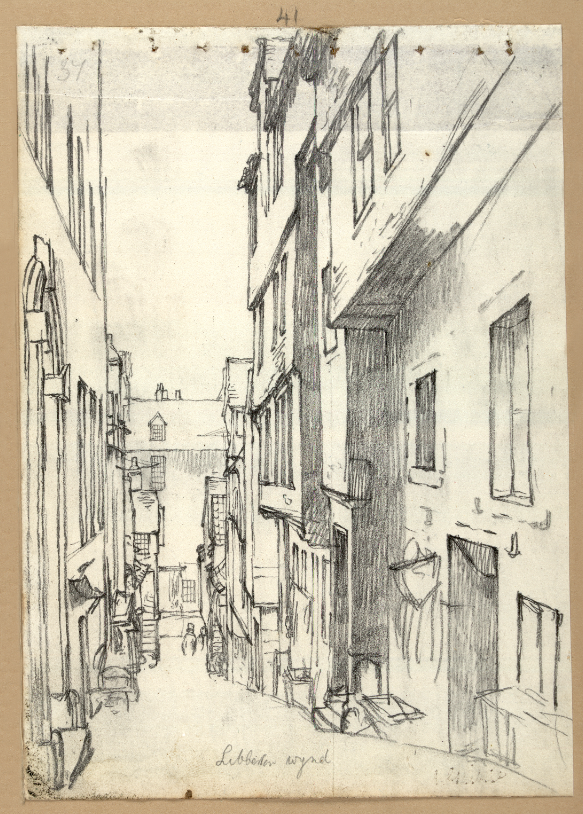

As the street existed prior to the advent of photography, surviving images of Libberton’s Wynd are found in works by several Edinburgh artists, including these depictions by Walter Geikie:

Walter Geikie became a common sight around Edinburgh, sketching street scenes and buildings, and provided illustrations of the infamous West Port murders of Burke and Hare for the local Press. Born in Edinburgh’s New Town in 1795, Walter suffered from a severe fever as a child which rendered him deaf and mute at the age of 2. Determined to ensure his son had an education, Archibald’s father – a pharmacist and perfumer – initially taught Walter himself at home before he was enrolled into Braidwood’s Institute, a pioneering school for children with hearing impairments. From a young age, Walter demonstrated artistic skill and his talents saw him attend drawing classes in the Edinburgh Trustees’ Academy; he would go on to publicly exhibit his works at the Edinburgh Exhibition Society and at the Scottish and Royal Scottish Academies, becoming a member of the Academy in 1834.

In his later years, Walter would carry a business card which he would show to those who could hear as a way of an introduction; despite any stigma which society may have then attached to such impairments, he would not let them become impediments. The card read, “Mr G. is unfortunately both deaf and dumb! What a misfortune. But nature has amply compensated in other aspects for these severe privations”.

Buried in Greyfriars’ Kirkyard following his death in 1837, his efforts to support the Deaf community of Edinburgh are now commemorated in a plaque on the Kirkyard’s west boundary wall. Collections of his etchings were published posthumously, as Etchings Illustrative of Scottish Character and Scenery executed after his own designs by the late Walter Geikie, Esq.

In March 1829, The Edinburgh Evening Courant reported that the materials of the buildings in Libberton’s Wynd were to be sold off by public roup on 24th March, while the tenement containing the tavern was also available for sale by public roup, on 25th March 1829, until the end of its lease on Whitsunday 1831. A surviving ‘Tappit Hen’ – a pewter vessel and drinking measure with a hen-shaped knob on the top of the lid – which was believed to have been used in Dowie’s, was saved and is now held within the collections of the National Museum of Scotland; it’s currently on display in Level 3 of the Museum’s Scotland Galleries (item ref. H.MET 37).

The Wynd’s end had come. First referred to in the late-15th Century, Libberton’s Wynd had been completely demolished by 1835 and the new bridge on which it was built was deemed usable. On 26th October, 1835, The Caledonian Mercury reported that the arch marking the northern entrance to Libberton’s Wynd had been taken down, thereby removing the “last vestige of that ancient alley”. A contributor to William Hone’s Yearbook of Daily Recreation and Information wistfully pondered its passing:

“A place of high note when its neighbourhood was the Court end of town, now, its shut windows, and the forsaken homes beside it, must in the minds of those who remember the mirth and madness which were ever at home – the roaring and roysting of its ever-coming customers – awaken the sober reflection, that time is quickly passing on, and making the things that were as though they had not been.”

Acknowledgements: Images kindly supplied by National Library of Scotland and Historic Environment Scotland/SCRAN