This week marks the centenary of the death of Scottish photographer John Thomson (1837-1921), one of the great names of early photography. Over the last 30-40 years Thomson’s achievements as a photographer, which were largely forgotten in the years following his death, have been increasingly recognised and publicised. A cast bronze plaque to commemorate him has been installed in Edinburgh by Historic Environment Scotland, outside 6 Brighton Street in the Old Town in Edinburgh, where the Thomson family moved in 1841 and where he spent the next 20 years of his life.

The plaque installation follows on from the restoration of his grave in Streatham Cemetery, south London, in 2019 (https://hpchina.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/2019/07/24/restored-the-grave-of-pioneering-travel-photographer-john-thomson/).

Thomson was born in Edinburgh and came from a relatively humble background. In the early 1850s he was apprenticed to a maker of optical and scientific instruments and became familiar with the principles of photography. He attended evening classes at the Watt Institution and the School of Arts, a mechanic’s institute in Edinburgh (the forerunner of Heriot-Watt University), gaining qualifications and a prize for English. In 1861 he became a member of the Royal Scottish Society of Arts.

By 1862, however, he made the decision to join his brother William in Singapore and embarked on a career as a photographer. He established a portrait studio there and also travelled around the Straits Settlements and began to take an interest in photographing indigenous peoples.

(Carte-de-visite from Thomson’s Singapore studio)

In 1865, Thomson embarked on his first major photographic journey. He sailed to Bangkok, where he took a remarkable series of portraits of King Mongkut of Siam and senior figures in the Siamese court and government. He also obtained permission from the King to travel into the interior of Cambodia, at the time under Siamese control. He spent two weeks in the ancient city of Angkor, taking the first photographs of this vast and beautiful site, which is now on the UNESCO World Heritage List. After photographing the Cambodian Royal Family in Phnom Penh, he returned to Britain, where he was able to publish his photographs of Siam and especially of Angkor. He lectured widely and became a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

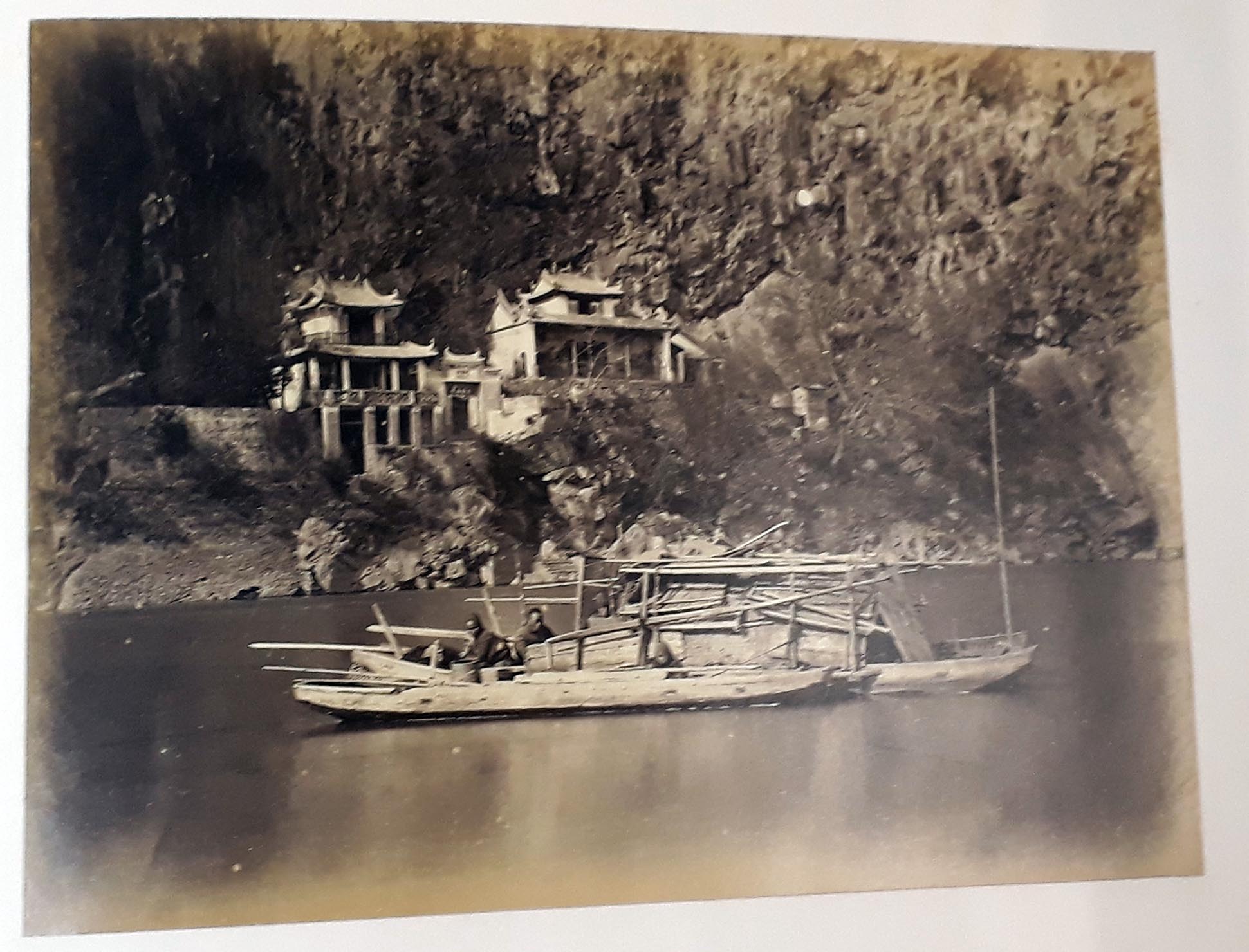

After a year back in Britain, Thomson returned to the Far East in 1867. He moved his studio from Singapore to Hong Kong and spent the next five years recording life in China. He travelled all over China, from the southern trading ports of Hong Kong and Canton to the city of Peking (Beijing) and the Great Wall in the north, and from the island of Formosa (Taiwan) to the interior of China, 3,000 miles up the River Yangtze. His subjects ranged from beggars and street people through to mandarins and princes, from imperial palaces to remote monasteries, and from rural villages to the grandeur of the Chinese gorges. He thus produced a range of photographs which revealed more of the culture and people of China than had hitherto been available to Western audiences.

Fishermen from “Views on the North River” (Hong Kong, 1870)

Often travelling with only his dog, Spot, as a companion, Thomson visited remote parts of China which had never before seen a camera, often placing himself in dangerous situations and relying on his engaging personality to develop a rapport with his sitters. His achievements become all the more remarkable when one considers the bulky equipment and chemicals he had to take with him. The majority of his work was produced using what is known as the ‘wet-collodion’ process to create a photographic negative on glass. This technology was complex and time-consuming. The glass negative had to be coated with chemicals, the image taken while the negative was still wet, and then developed in a portable darkroom on the spot. Thomson often had to improvise when chemicals became impossible to source. He used a variety of cameras, both full-plate and stereo, but none of his instruments have survived. They had to be strong but relatively portable and were made from hard woods to withstand tropical climates.

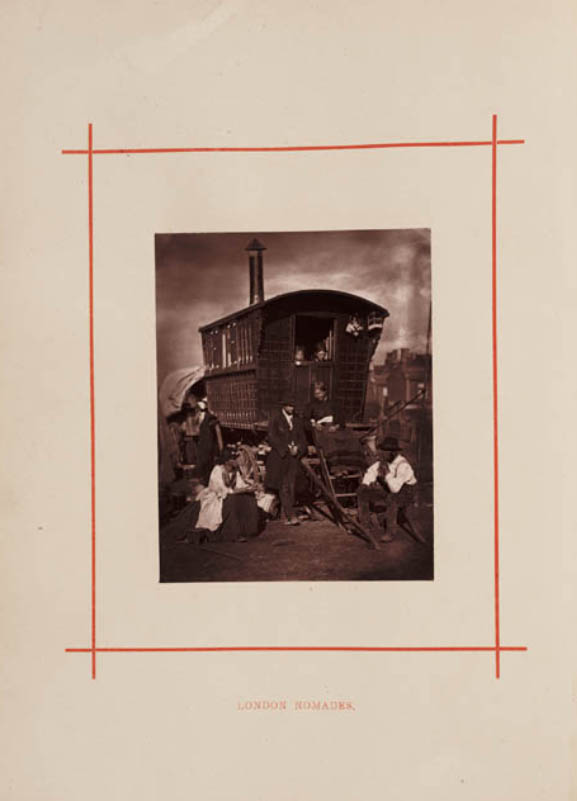

Thomson returned to England in 1872 with his family, settling in London. He lectured and published on his travels in the Far East in magazines and photographically illustrated books, most notably the four-volume work “Illustrations of China and its people” (1873-1874). He also wrote extensively on photography, contributing numerous articles to photographic journals, such as the “British Journal of Photography”, and edited and translated French author’s Gaston Tissandier’s “La photographie” (“History and Handbook of Photography”) (1876) which became a standard reference work. Moving to London also gave him the chance to renew his acquaintance with Adolphe Smith, a radical journalist whom he had met at the Royal Geographical Society in 1866. Together they collaborated in producing the monthly magazine “Street Life in London” from 1876 to 1877. They documented with Thomson’s photographs and Smith’s text the lives of the street people of London, in what was an important early work of photojournalism. The photographs were later published in a book of the same title in 1878.

(Travellers from “Street life in London”)

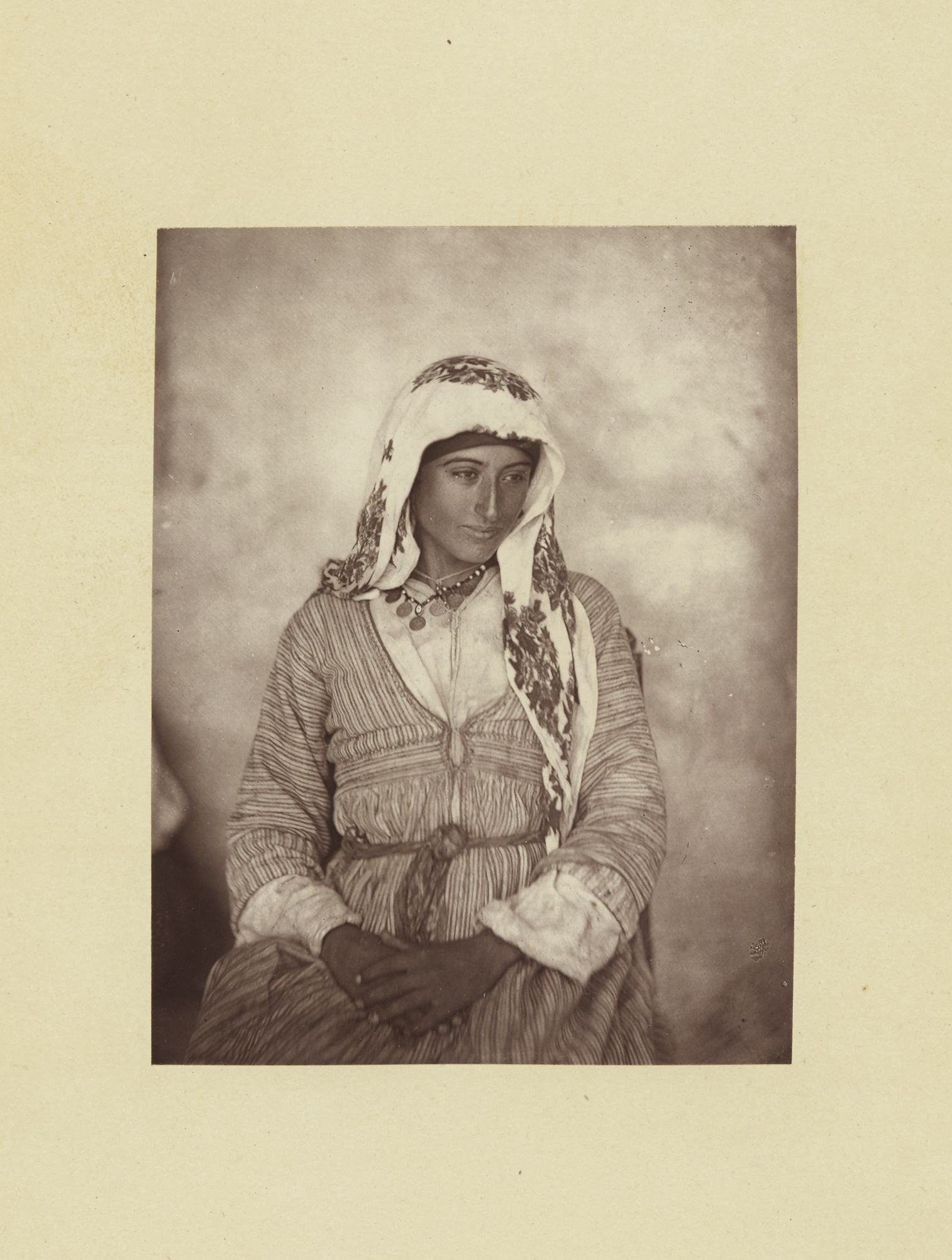

In the same year, 1878, Thomson made one final overseas trip with his camera, to the island of Cyprus, which had just become a British-governed protectorate. He took a series of evocative images of the island and its people, which were published in “Through Cyprus with the camera”.

Cypriot woman from “Through Cyprus with the camera”

He later became a member of the Photographic Society, later the Royal Photographic Society, and opened a portrait studio in Buckingham Palace Road. In 1881 he was appointed photographer to the British royal family by Queen Victoria, and his later work was devoted to studio portraiture of the rich and famous. This new career path was a marked contrast to his earlier work in London and the Far East, but it gave him a good and steady income. He had a long and fruitful connection with the Royal Geographic Society, including instructing explorers in the use of photography to document their travels. He continued to write papers for the RGS after he retired from commercial photography in 1910 and was elected a Life Fellow of the Society in 1917. He spent a large part of his post-retirement life back in Scotland, before dying of a heart attack on a tram in Streatham Hill in 1921.

Shortly before his death Thomson had approached the noted collector Sir Henry Wellcome about acquiring the collection of glass negatives he had amassed during his travels in the Far East. Wellcome was able to purchase them after Thomson died. They have been preserved for posterity in the Wellcome Library’s collections in London and have been digitised and made available via the Wellcome Collections website (https://wellcomecollection.org/collections).

In 1997 the Library held an exhibition “Captured shadows” devoted to Thomson’s life and work, curated by Richard Ovenden, then a curator in the Library’s British Antiquarian division. Richard also wrote a book on Thomson to accompany the exhibition, “John Thomson (1837-1921): photographer”. The exhibition featured new prints of Thomson’s photographs, which were produced from the original negatives in the Wellcome Library and by using the same processes that Thomson would have employed. These prints and some of Thomson’s photographically illustrated books are available for consultation in the Library’s Special Collections Reading Room.

In recent years Thomson’s work has been further popularised by photo historian Betty Yao MBE, who created the travelling exhibition “Through the lens of John Thomson” (http://www.johnthomsonexhibition.org/), which has visited several venues around the world, and which will be hosted by Heriot Watt University in Edinburgh from 30 September 2021 to 24 March 2022.

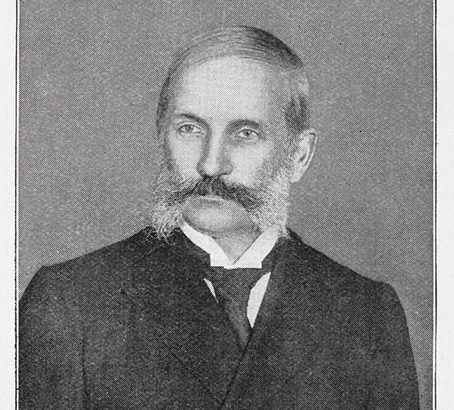

(Photograph of John Thomson aged 60. Image courtesy of Special Collections (Carstairs Collection), University of Bristol Library (www.hpcbristol.net)).