Examine a terrestrial globe and what do you see? A fascinating model of how we view the world? A historical snapshot of the various landmasses and water features we have encountered? Or are globes a political narrative reflecting the creator’s point of view?

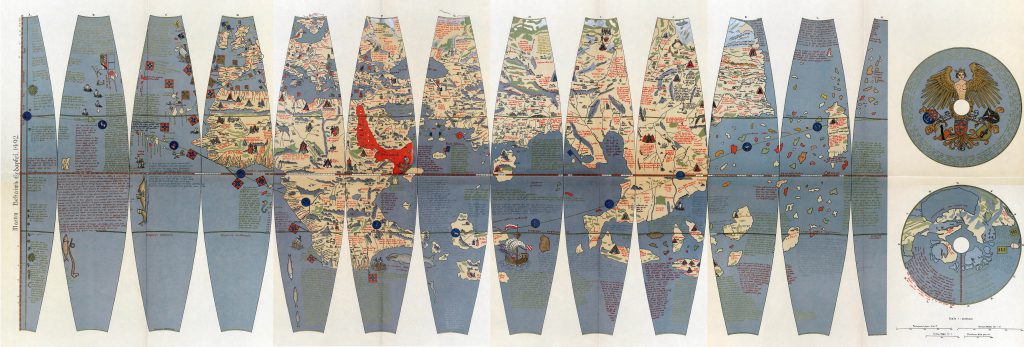

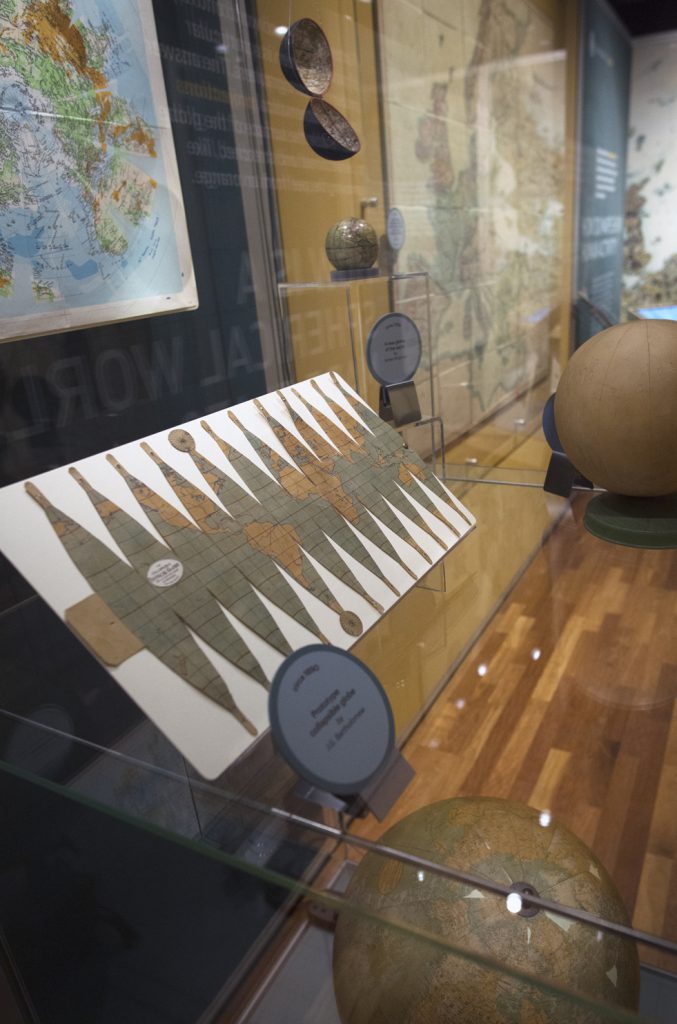

Globes have been used as important navigational and political tools, status symbols and educational resources. The oldest surviving globe is the model of the celestial sphere in the Farnese Atlas, a 2nd-century marble sculpture of the Titan Atlas, who, in Greek mythology, was condemned to hold up the heavens for eternity. Although early globes were created by the ancient Greeks and throughout the medieval Islamic world, few have survived. The oldest surviving terrestrial globe is the Erdapfel, often credited to Martin Behaim. This 15th-century globe predates Columbus; consequently the Americas are missing. In the early 20th century, Ravenstein created a facsimile of Behaim’s globe in the form of 15 distinct two-dimensional strips. Such strips are known as ‘globe gores’.

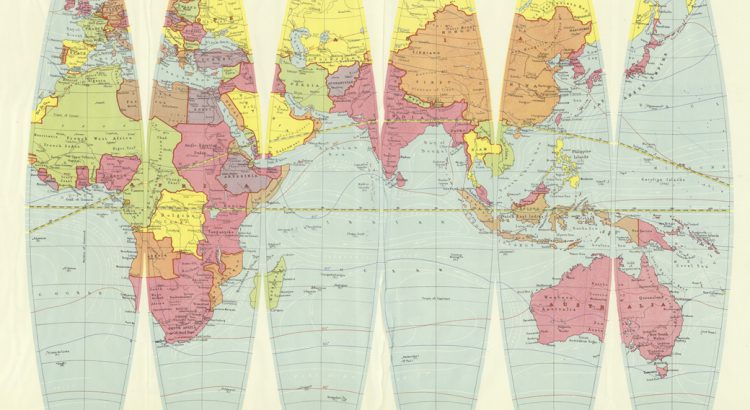

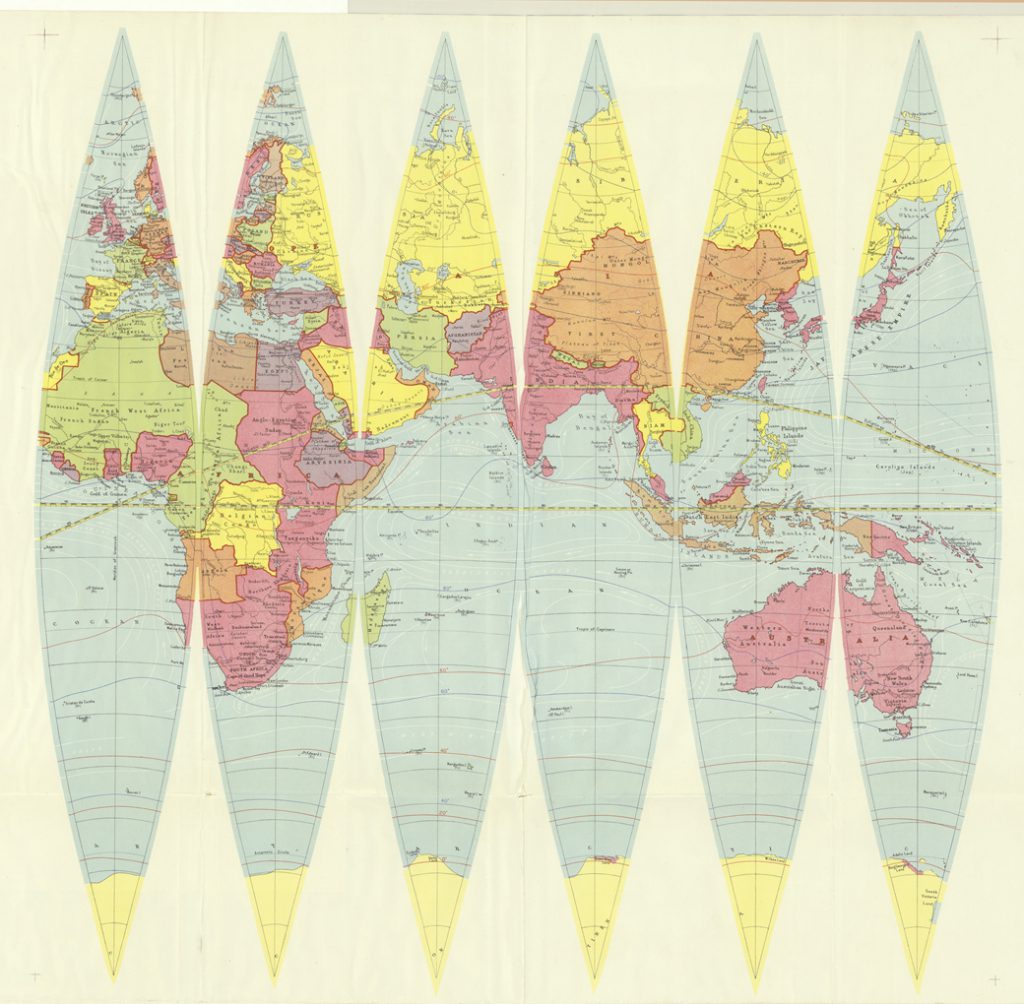

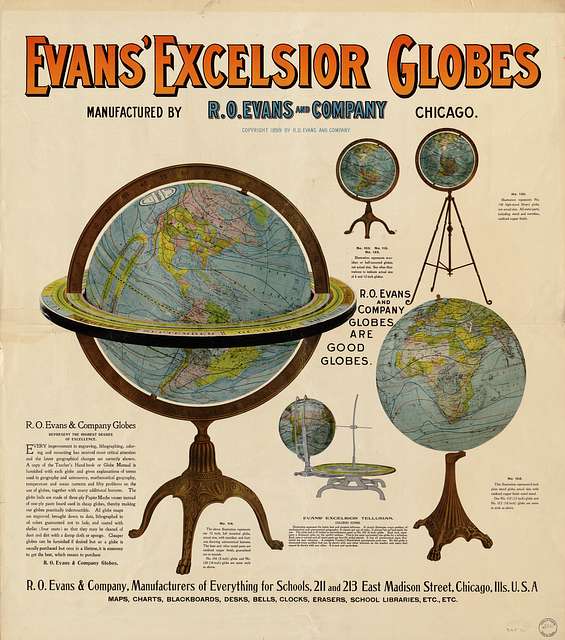

During the late 19th century and earlier 20th century, globes became popular teaching aids. The Paris Peace Treaties created a changing geopolitical landscape and a need for more up-to-date maps and globes. Following this treaty, globes became more popular in the classroom setting. One example of globe gores created for educational use is Denoyer-Geppart’s 12-inch globe gores:

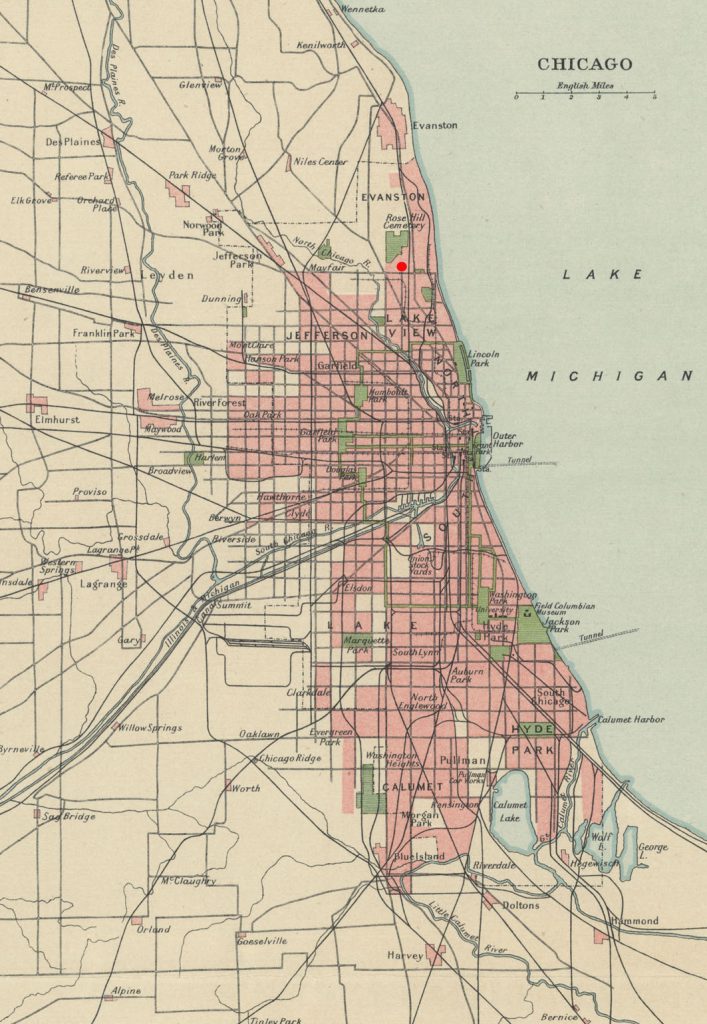

Denoyer-Geppert Co. was founded in 1916 by Otto E Geppert and L Philip Denoyer. The firm primarily published maps, atlases and globes for educational use. It was located at 5253 N. Ravenswood Ave, slightly south of Rosehill Cemetery, in Chicago.

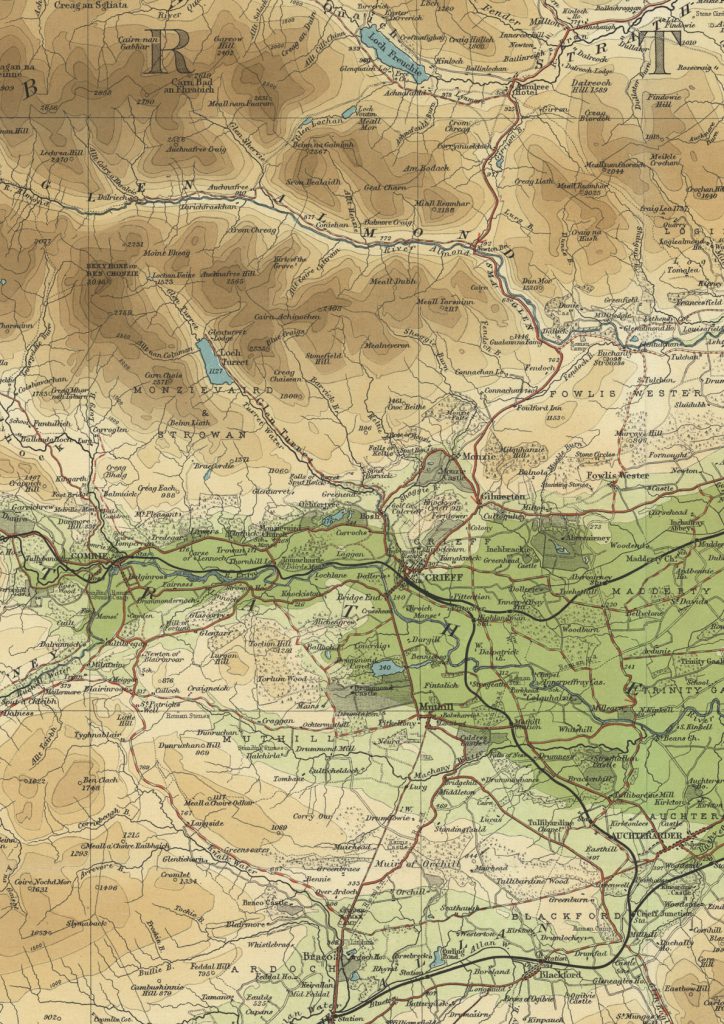

The 12-inch globe gores are part of the Bartholomew Printing Record in the National Library of Scotland collections. The Bartholomew Firm were an internationally renowned family of map engravers. The Bartholomew archive includes every map printed over the 180 years of the Bartholomew firm. They had a reputation for precise current mapmaking and inventive colour contouring techniques (as shown below):

https://maps.nls.uk/view/97130758

Utilising Bartholomew’s expertise was not the only international connection between Edinburgh and Chicago: Otto Geppert had previously been employed by an American branch of the Scottish map publisher A.K. Johnston, and Denoyer-Geppert’s initial cartographer was the Edinburgh-trained R Baxter Blair.

During the production of these globe gores Denoyer-Geppart’s business was flourishing. An article in the Journal of Education by Winship (1922) raves about Denoyer-Geppart’s catalogue containing “…1,200 maps, charts, globes and associated aids for teaching geography and history…”

During the Second World War, Denoyer-Geppert’s firm were still creating globes and wall-maps predominantly for education use. One of their noteworthy creations was a 20-inch wartime globe that could be written on with chalk, with blue water, black landmasses and a gold outline. These globes were popular with the military and often used in military training. Denoyer-Geppert’s reputation for globe making grew and they were asked by NASA to build a lunar globe to commemorate Apollo 10 in 1967. This globe used footage and photographs from the Apollo 10 mission and became one of the most realistic portrayals of the moon.

In 1984, Denoyer-Geppert Co’s cartographic inventory was bought out by R & McNally, but the firm continues to sell biological models for schools.

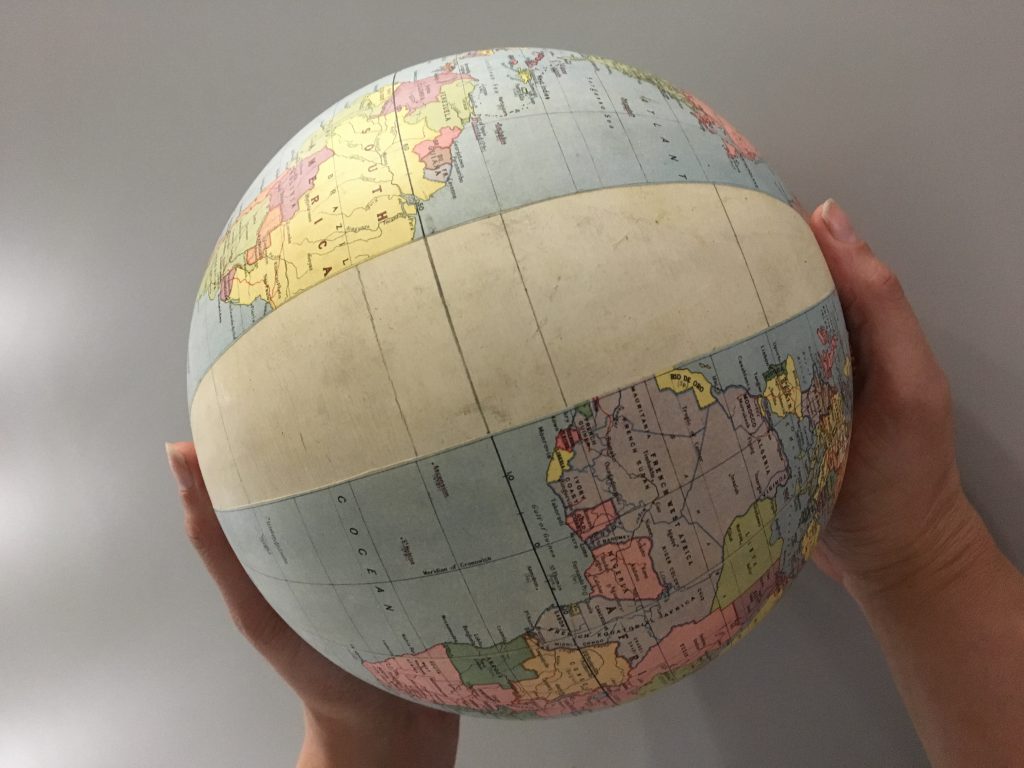

Building a globe is a unique puzzle. A map sheet presents the challenge of representing a spherical world upon a flat surface. This is fundamentally the aim of map projections: different mathematical transformations convert our round earth into the familiar flat sheet of a map. Globes are a slightly different story. They pose the question of how to fit a flat representation of the earth onto a round surface. This puzzle is neatly illustrated with the help of an orange prepared by a talented colleague:

Each orange segment could represent a different globe segment or globe gore. Traditionally, globes were built by plastering the map segments onto a round surface like the almost complete globe below. The globe maker would carefully ensure that the gores were perfectly flat before lacquering the surface for durability.

Over the years, globes have been built from different materials, including cardboard, metal, glass and plastic. Some have been created by etching directly onto metal or glass. More recently globes have become available in digital form, rendered on computer displays that allow viewers to interact with a two-dimensional image as if it were a three-dimensional object, completing a circle from 2D image to 3D globe back to a 2D image again.

Globe gores, being map pieces that are joined together create a sphere, are both projections and puzzles. The connection between puzzles and projections is explored in our display at the top of the staircase in the NLS George IV Bridge building. As part of this project, we have created some cut-and-fold globes that you are welcome to pick up at George IV Bridge or download below:

We hold a few complete globes in the National Library of Scotland Maps Collections, but these are primarily for demonstration. If you would like to view more globes, we would recommend visiting National Museums Scotland (www.nms.ac.uk).

There are also several globe gores in the map collections, including facsimiles of classical terrestrial globes such as the Sanuto Globe Gores and Coronelli’s Libro del Globi, globe gores intended for educational use and globe gores in Malay and Telugu

For further information, see the journal Globe Studies by the International Coronelli Society for the Study of Globes.