Some of the most detailed and alarming military maps of Scotland were made by external aggressors, planning attack or invasion. Here we look at maps made by four of these countries:

French charts, 1800s

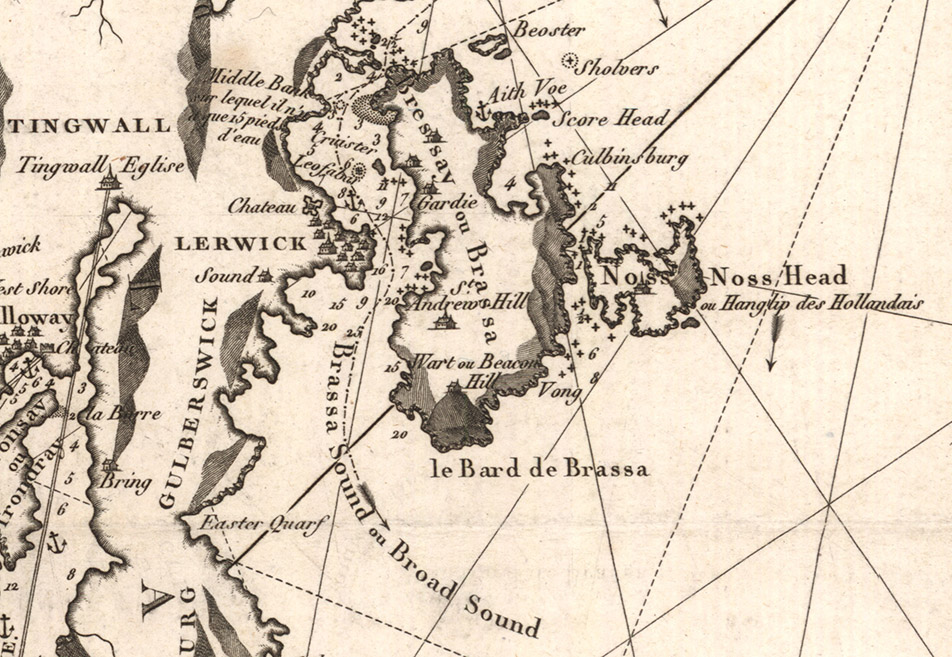

In the early 18th century, when Napoleonic France made preparations for an invasion of Great Britain, the best available charts of British coasts were hastily gathered by the French Dépôt Générale de la Marine. For Shetland, the most useful chart they could lay their hands on had originally been drawn some sixty years earlier by an English mariner, Thomas Preston. Preston had been transporting tobacco from Virginia to London when his vessel was wrecked in the Skelda Voe region. Whilst he was detained in Shetland, Preston put his time to good use in drawing a detailed chart of the islands, which was subsequently used by grateful mariners for the rest of the century. Preston’s chart was also improved upon, especially in terms of its positional accuracy, by later chart makers – it was updated by R. Sayer & J. Bennet in 1781, and by Paul de Loewenorn, a Danish naval officer, in 1786.

So the French invasion chart of 1805 had a long and interesting provenance through English and Danish hands, showing a combination of Norn, English, Dutch and French captions and place names – see, for example ‘Noss Head, ou Hanglip des Hollandais’. Although the chart does show the recently reconstructed Fort Charlotte in Lerwick, marked as ‘Chateau’, then the most significant military stronghold in the islands at this time, this is largely an accident, because the fort was originally built in the 1660s, and appears on Preston’s chart. Fortunately for Shetlanders – as well as perhaps for the French too, given how out-of-date and limited in detail the chart was – the invasion never happened…

English maps, 1540s

In contrast, when the English invaded Scotland in the 1540s, they brought their own professional map-makers with them, giving them clear tactical advantages. The Rough Wooing campaigns into Scotland involved the most extensive use of maps in a military context to date in Britain. When Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, invaded Scotland in 1547, his entourage included the leading English map-makers of the day, including Richard Lee and Thomas Petit, as well as the Scottish spy and map-maker John Elder. The earliest overhead plans drawn to scale in Britain date from this time (including the fortress at Eyemouth), as well as the earliest surviving regional maps of Scotland showing distances between castles and towns.

The maps and views from this time are also an excellent documentary source for the Battle of Pinkie, the last pitched battle fought between the Scottish and English armies. This copperplate engraving of the battle (above), attributed to Thomas Geminus, is a very early example of a “news” map, and cleverly combines several stages of the battle into one. The Duke of Somerset had marched around 18,000 men north from Berwick-upon-Tweed, supported by an armada of eighty ships. The Scots army was even larger, perhaps between 20,000-30,000 men, but less well-armed. The two armies met on the banks of the River Esk, near Musselburgh on 10 September 1547. In spite of heavy English cavalry losses, the Scots advance was stalled, and a tactical retreat became a rout. Perhaps around 6,000 were killed and 1,500 taken prisoner. Yet whilst this was a dreadful defeat for the Scots, Somerset had failed in his central mission of forcing the Scots to accept the marriage of Henry VIII’s son Edward to the infant Mary Queen of Scots. Within three years, the English troops had been forced to withdraw.

German maps and photographs, 1940s

Following the successful German invasions of Poland, Norway and France (1939-40), Hitler’s attentions turned to Britain, and ‘Fuhrer Directive No 16’ was issued in July 1940, preparing for a landing operation against Britain, known as ‘Operation Sealion’. Significant resources were devoted to the project, particularly in research and documentation, with maps, photographs and detailed written reconnaissance.

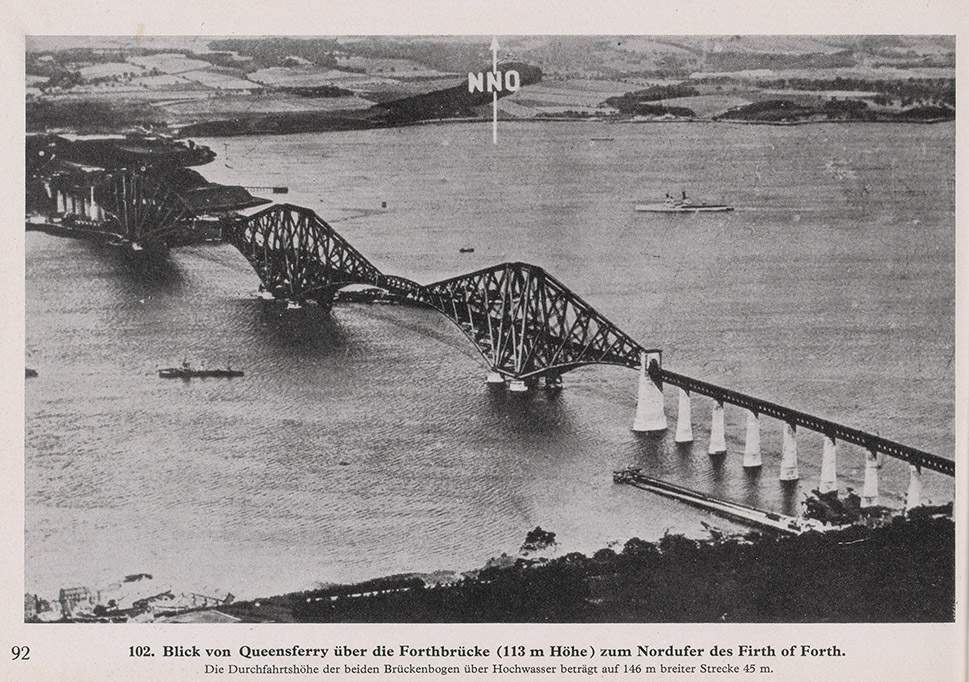

The German Army’s publication Militargeographische Angaben uber England : Ostkuste – (Nordlicher Teil vom Humber bis zum Firth of Tay) / Military Information on England: East Coast – (Northern part of the Humber to the Firth of Tay) gives a good flavour of the high quality of this information. Most of the booklet consists of photographs, sometimes from aerial reconnaissance, and others from pre-War picture postcards, which collectively give an excellent impression of the landscape and terrain that the German army might find itself in. For example, the air photo of the Forth Bridge (above) gives details of the distance between the bridges and height above the water of this key infrastructure target.

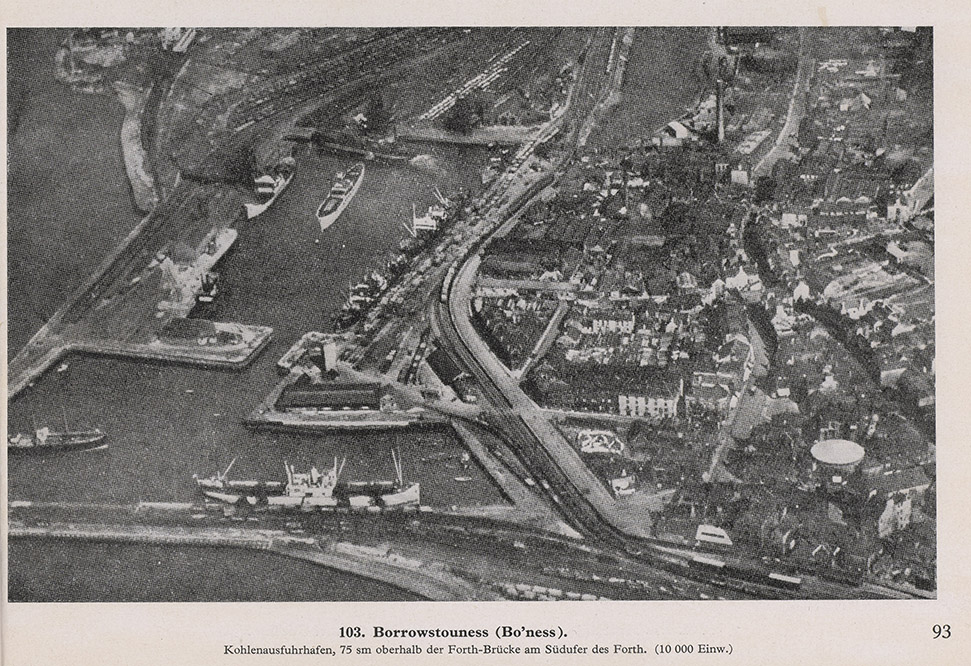

The accompanying air photo of Bo’ness (above), correctly refers to it as ‘Coal export harbour, 7.5 miles above the Forth Bridge on the south bank of the Forth (10 000 inhabitants)’.

These air photo locations are clearly shown as purple circles with numbers on the accompanying maps (above), originally printed by Ordnance Survey in the 1930s, but re-used by the Germans and colour-coded to show the type of coast for landing. The red overprint indicated cliffs and steep gradients, whilst green and yellow indicated flat and sandy shores. It is clear that if the Germans had invaded, they would have been supported by excellent cartographic information, especially for coastal areas.

Russian maps, 1980s

Russian military maps have a distinguished pedigree, and in the twentieth century they became the most extensive, detailed military mapping ever produced, with global coverage. Military concerns were integral to their development. The Russian Military Topographic Directorate (VTU) was founded in 1812, five months before Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia. Then in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, a massive expansion in state cartography took place, given further impetus by the Second World War. By 1957, the entire territory of the Soviet Union had been mapped at a scale of 1:100,000 (over 13,000 sheets), whilst a much larger project to map the whole world was well underway. It is only following the disintegration of the Soviet Union in the 1990s that many of these formerly secret maps of parts of Britain and Scotland became generally available in Western, non-military circles, allowing something of their history and content to be studied.

Soviet military maps cover the world at a set of scales from 1:1 million to 1:10,000, and at each of these scales, they conform to a consistent specification, using the same standard symbols, projection and grid. The immense value of this for facilitating their interpretation and use by military personnel cannot be overemphasized; military commanders or soldiers in wartime scenarios had no need to cope with a foreign cartographic map series, with its own alien style, symbols and language.

On the Russian 1:1 million scale map of Scotland (above), coastal information is particularly strong with lighthouses shown by stars, and the “boat” symbol for civilian seaports / harbours ( such as for Wick and Helmsdale). Three different types of rocks are distinguished, by whether they are visible at high tide, low tide or intermediate tides. Inland, apart from the significance of the terrain itself, including rivers, lochs, and major areas of woodland, the maps pick out communications, particularly by rail and road. Note too the military airfield at Dounreay (civilian airfields were shown with a grey aeroplane symbol). Smaller-scale Russian military maps such as this were excellent for general terrain evaluation and allowing a strategic overview of wide areas. However, the Soviet army also mapped several of the larger Scottish towns at detailed scales of 1:10,000, including Aberdeen.

Mapping the military history of Scotland

Maps have immense power. They not only can change the way we think about the world, but also the way we act within it too, and arguably this power can be seen in its most profound way through military maps. Over time, these maps have deliberately encouraged their users towards destructive ends: to attack other countries, to destroy buildings, infrastructure and resources, and even to kill their fellow human beings. Of course, maps are not solely responsible for guiding destructive actions, and maps also reflect great ingenuity, intelligence and expertise, not least in planning and showing imaginative defensive works, constructing protection from other aggressors. But whatever their purpose, as warfare has flared up and down over the centuries, maps have been an essential tool for both sides.

Scotland: Defending the Nation – Mapping the Military Landscape, by Carolyn Anderson and Christopher Fleet, has just been published by Birlinn, in association with the National Library of Scotland. It uses six centuries of military maps to examine Scotland’s unique and fascinating military history. The selected maps begin in the 1450s and come through to the latest digital mapping, with each map telling its own story as part of a broader narrative. Most of the maps are from the rich collections of the National Library of Scotland.