In 1810 the schoolteachers Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie found their Edinburgh boarding school abandoned after the rapid removal of every single pupil by their parents. The reason for this exodus stemmed from the accusations voiced by their pupil Jane Cumming who informed her grandmother that the two teachers were in a sexual relationship.

Horrified by the forced closure of their school and the loss of their livelihood, the pair sued Jane’s grandmother, Lady Cumming Gordon, for libel denying the accusations of “lewd and indecent behaviour” and that any such relationship existed between them.

The pair won the case, but further appeals and legal fees meant that most of the money they acquired from the trial for their loss of livelihood never reached them. Eventually Marianne moved to London and was able to find employment there, while Jane Pirie stayed in Edinburgh and, unable to find employment, reportedly suffered a nervous breakdown.

The question of whether the accusations made by Jane Cumming were true was central to the debate in court. The judges were faced with two opposing claims, which each challenged the assumptions of the day.

On one hand the judges found it difficult to believe that such activities between women existed, let alone that two respectable Scottish schoolteachers would engage in such activities. On the other they found it just as difficult to believe that a Scottish schoolgirl would just make the whole thing up.

In order to find a solution to this dilemma the teachers’ case leaned heavily on colonialist attitudes. The focus came down on Jane Cumming’s race and upbringing. Jane was born to an Indian mother in India and had spent the first part of her life there, until she had been moved to Scotland by her father.

It was in her upbringing and race that the court placed the origin of her accusations and her interpretation of the sounds and movements she witnessed. This allowed the judges to see the accusation as being due to the influence of ‘foreign’, ‘deviant’ sexuality rather than having to consider that middle-class white Scottish women might partake in such activities, thus breaking the mental deadlock.

From a detailed reading of the case today, Jane Cumming’s interpretation of events seems more likely than the court’s judgement. Since the case took place there have been multiple reinterpretations of this case each making a separate judgement on the truth of Jane Cumming’s accusations.

William Roughead’s true crime anthology Bad Companions (1930) states that his interest in the “case resides in the fact that the charge was false; also in the astounding audacity of the traducer, and the long legal duel to which her precocious wickedness gave rise.” His sympathy for Marianne and Jane Pirie comes from the falseness of the charges: he says that “had the accusations been well founded, nothing would have induced [him] to deal with it”.

From his perspective Jane Cumming was a cruel liar who wilfully and pettily destroyed the lives of two women without cause. This interpretation is echoed in the play The Children’s Hour by Lillian Hellman (1934).

Inspired after having read Bad Companions, Hellman adapted the events, removing Jane Cumming’s racial background and inserting a novel as the inspiration for her accusations, Hellman reimagines a version of events in which, despite the accusation being false, the pair lost the trial. Finally, following the confession of her love for her friend one of the women ends her own life.

Here sympathy relies not on the accusations being false but being unconsummated. Since then, the story has been reinterpreted twice more in film. First as a heterosexual love triangle involving accusations of infidelity and as a close adaptation of The Children’s Hour play starring Audrey Hepburn (1961). Each version created a slightly different version of the events.

The question of whether there was any truth to the accusation made by Jane Cumming is one that, despite the judgements of the court, remains unanswered. However the events of their lives will continue to be revaluated for years to come.

Alex Wilson

LGBT+ History Intern

Collection items featured:

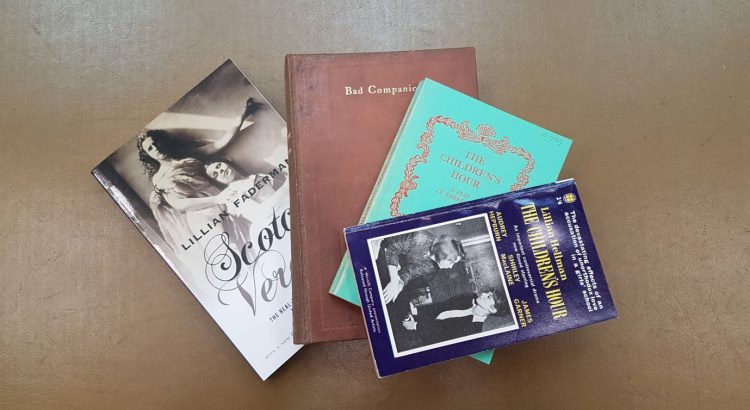

Faderman, Lillian. Scotch Verdict: Miss Pirie and Miss Woods v. Dame Cumming Gordon. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1983.

Faderman, Lillian. Scotch Verdict: The Real Life Story Which Inspired The Children’s Hour. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Hellman, Lillian. The Children’s Hour. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1937.

Hellman, Lillian. The Children’s Hour. London: The English New Library Ltd, 1962.

Hellman, Lillian. The Children’s Hour. New York: Dramatists Play Service, 1953.

Roughead, William. Bad Companions. Edinburgh: W. Green and Son Limited, 1930.