By Ash Charlton, collaborative PhD student on placement with Rare Books.

Please note that some material in the collection and the language that describes them may be harmful. Read our statement on language you may encounter when using the collections.

The National Library of Scotland holds a wealth of information, including a substantial collection of pamphlets relating to slavery. As part of my placement, I worked on improving catalogue records for a selection of these pamphlets and this short blog series (1 of 3) will highlight some interesting finds. This covered 35 bound volumes, totaling 355 pamphlets.

Elizabeth Heyrick

A high proportion of these pamphlets were written by men, although one prolific female author can be singled out: Elizabeth Heyrick (1769-1831). Heyrick was a firm abolitionist, philanthropist and Quaker and her publications ranged from addressing low wages, to animal rights and corporal punishment. She lived through a period of rising disquiet around slavery, the slave trade and rising abolitionist sentiment, where she became a strong anti-slavery advocate.

In Great Britain, the Slave Trade Act 1807 had prohibited the slave trade within the British Empire, however it did not stop the act of slavery itself. When it became clear that the 1807 act was not going to lead to a decline in slavery in the British West Indian colonies due to economic interests, the gradualist approach of British politicians was brought to the forefront of public debate. This sparked a renewed support for the idea of immediate abolition, although support for this movement was not solidified until the 1830s, and the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833.

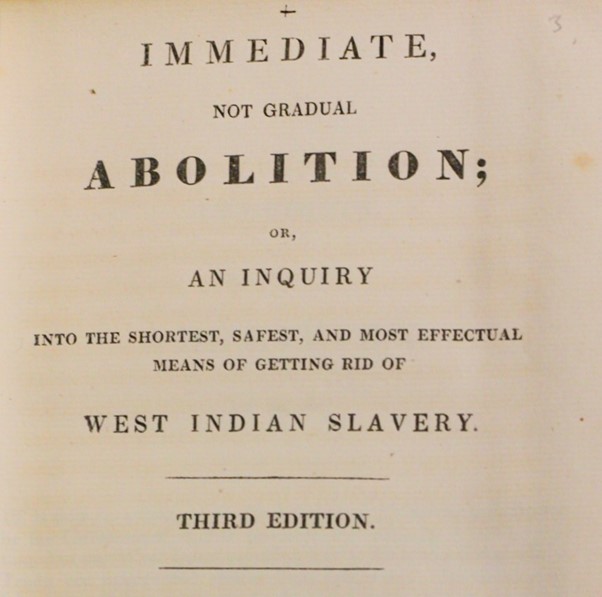

Heyrick’s 1824 pamphlet Immediate, not gradual abolition; or, An inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian slavery was one of the few at the time arguing that abolition should be immediate, not a gradual process. She describes an immediate approach as ‘more wise and rational, more polite and safe, as well as more just and humane’ (page 16) than a gradualist approach. Heyrick also argues that since Britain’s abolition of the slave trade in 1807, ‘England has only transferred her share of it to other countries’ (page 3). In response to inaction and a slow pace of change, she calls for ‘abstinence from the use of West Indian productions, sugar especially’ (page 4), explaining that only the removal of the markets supported by the labour of enslaved people would propel emancipation forward.

‘Immediate, not gradual abolition’ Shelfmark: 3.1672(3)

Another of her pamphlets, No British slavery; or, An invitation to the people to put a speedy end to it was also published in 1824, emphasising the need for immediatism in the abolition debate. She opened her pamphlet with a rousing call to action that reiterated the need for the people of Great Britain to come together in action:

MY COUNTRYMEN! You, especially, who contribute the great body of the people, who labour hard for your daily bread, and imagine you have neither time nor talent for the reform of public abuses; rouse yourselves into a sense of your own importance and dignity. Here is a great and glorious reformation in hand, which cannot be accomplished without your assistance.

Heyrick goes on to outline the treatment of enslaved people by their enslavers ‘not as a human being, but as a beast of burden, whom he buys and sells like cattle in market;- whom he drives and keeps to labour, all year round, with a cartwhip, applied without mercy’ (page 3). Heyrick brands the horrors of slavery as ‘a crying sin and crying shame’ (page 7) and appeals to her readers’ Christian morals to support the immediate end of slavery. She closes her pamphlet on an appeal to follow divine law and ‘love our neighbour as ourselves and do unto others whatsoever we would that they should do unto us’ (page 8).

Women’s Anonymous Publishing

Many of the pamphlets I catalogued were published under cryptic names rather than the author’s real name, such as ‘A Northern Man’, ‘A Briton’, ‘A Merchant’ and ‘A Barrister’ among many others. The choice to publish under a pseudonym may have been for privacy reasons or to preserve reputation, perhaps as the topic of slavery was a highly debated one in the public spheres of eighteenth and nineteenth-century Britain.

One pamphlet, Slavery past and present; or, Notes on Uncle Tom’s cabin, published by ‘A Lady’ (1852), expresses support for the American anti-slavery book Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896). Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a popular publication that sold hundreds of thousands of copies in both the United States and Britain and condemned slavery as an evil and immoral act, although it has since been criticised for reinforcing negative racial descriptions. On release, the novel was divisive, prompting outcries against it by supporters of slavery, whilst abolitionists praised the book for its pro-emancipation and Christian sentiments.

Stowe’s novel was popular in Britain and in 1853 a group of high-profile women came together in support of the US anti-slavery sentiment expressed in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Led by Harriet Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, The Duchess of Sutherland (1806-1868), this group including duchesses and ladies came together for what was to become known as the Stafford House Address. It was an appeal from the women of England to the women of America to act against slavery, which had not yet been abolished there. There are two pamphlets published by ‘An Englishwoman’ in 1853 in reaction to the Stafford House Address and its fallout in the newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic.

In one pamphlet, A letter to those ladies who met at Stafford House in particular, and to the women of England in general, on slavery at home, ‘An Englishwoman’ addresses the women at Stafford House petitioning against slavery in the United States to remind them of the poverty prevalent in Britain at the time:

The blessed sun of liberty shines over happy England and the cries of misery and poverty, in our own land are drowned in the many voices raised to implore the ladies of another country to look with pity on the sufferings of their own poor. Justly may they bid us remember that “charity begins at home.” (page 10)

This author claims not to have written this plea to the women of England in ‘a bitter spirit’ (page 23), however claims she could not in good conscience add her name to the anti-slavery petitions focused on American slavery. This paints a complex image of reactions to slavery elsewhere after Britain had abolished it in its colonies and reflects the tensions of trying to enforce change over international boundaries.

There are several other pamphlets in the collection that were likely written by women due to their chosen pseudonyms (although there may be more published under other pseudonyms that do not refer directly to the author’s gender). There are anti-slavery sentiments addressed in pamphlets by ‘A Lady’ in 1825 and ‘A resident in the West Indies for thirteen years’ in 1853, who has been identified as a Mrs. Campbell, although little is known about her.

The record of these pamphlets helps to identify the active contributions that women were making in the debates on slavery in Britain, the United States and West Indies through the nineteenth century and help to form a picture of the wider anti-slavery movement.

For more information on slavery in our collections see our guide on Scotland and the slave trade and our learning resource on anti-slavery activists.

Pamphlets

An Englishwoman. A letter to those ladies who met at Stafford House in particular, and to the women of England in general, on slavery at home (London, 1853). Shelfmark: 3.1521(6)

An Englishwoman Remarks occasioned by strictures in the Courier and New York Enquirer of December 1852, upon the Stafford-House address. In a letter to a friend in the United States (London, [1853]). Shelfmark: 3.1521(7)

A Lady. A dialogue between a well-wisher and a friend to the slaves in the British colonies (London,[1825]). Shelfmark: 3.1672(6)

A Lady. Slavery past and present; or, Notes on Uncle Tom’s cabin (London, 1852). Shelfmark: 3.1520(5)

A resident in the West Indies for thirteen years [Mrs. Campbell] The British West India colonies in connection with slavery, emancipation, etc. (London, 1853). Shelfmark: 3.1521(8)

Heyrick, Elizabeth. Immediate, not gradual abolition; or, An inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian slavery (London: [1824]). Shelfmark: 3.334(6), 3.2798(10)

Heyrick, Elizabeth. Immediate, not gradual abolition; or, An inquiry into the shortest, safest, and most effectual means of getting rid of West Indian slavery : with an appendix, containing Clarkson’s comparisons between the state of the British peasantry and that of the slaves in the colonies, &c. (London: 1824). Shelfmark: 3.1672(3)

Heyrick, Elizabeth. No British slavery; or, An invitation to the people to put a speedy end to it (London: 1825). Shelfmark: 3.2798(11)

Further reading

Newman, Richard S., ‘The time is now: The rise of immediate abolition’, Abolitionism: A Very Short Introduction, Very Short Introductions (New York, 2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 23 Aug. 2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780190213220.003.0004. Accessed 22 Mar. 2023.

Pugh, Evelyn L. “Women and Slavery: Julia Gardiner Tyler and the Duchess of Sutherland.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 88, no. 2 (1980): 186–202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4248387, Accessed 22 Mar. 2023.