April 2021 is the 250th anniversary of the publication of the sentimental novel The Man of Feeling by Henry Mackenzie in which the naïve Harley, in a series of fragmented episodes, encounters and weeps over the misfortunes of others and falls prey to the artfulness of more worldly characters. The book was a huge success on publication and the ESTC records over 30 editions printed (in English alone) before the end of the 18th century, not just in the British Isles but in North America, France and Germany. But who was Henry Mackenzie, what do we mean by a sentimental novel, and who, or what, was a man of feeling?

Mackenzie was born at Edinburgh on 26 July 1745 to Margaret Rose of Kilravock, eldest daughter of the sixteenth baron of Kilravock and her husband Joshua Mackenzie, a physician. He attended Edinburgh’s high school from 1758 to 1761 and continued his education at the University of Edinburgh before travelling to London in 1765 to study English exchequer practice. He returned to Edinburgh in 1768 to become a partner of George Inglis of Redhall, king’s attorney in exchequer, and began work on The Man of Feeling. Such was the success of The Man of Feeling that it became a soubriquet by which Mackenzie himself was widely known, despite the fact that in reality he was an astute man of business and a very different character to Harley. Throughout his life Mackenzie maintained both successful legal and literary careers: he was appointed comptroller of taxes for Scotland in 1779 and wrote further novels, including The Man of the World (1773), and several plays. He also became one of Scotland’s leading literary critics and produced two periodicals: The Lounger (1785-1787) and The Mirror (1779-1780). These weekly magazines were the first of their kind in Scotland and were largely written by Mackenzie who used them to promote his vision of polite society. The 9 December 1786 issue of The Lounger is notable for its positive review of Robert Burns’s Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect in which Mackenzie coined the phrase “heaven-taught ploughman” to describe the poet. He died on 14 January 1831, mourned by the Edinburgh Evening Courant as one of the last of that “eminent class of literary men, who, about fifty years ago, cast such a lustre on our city.“.

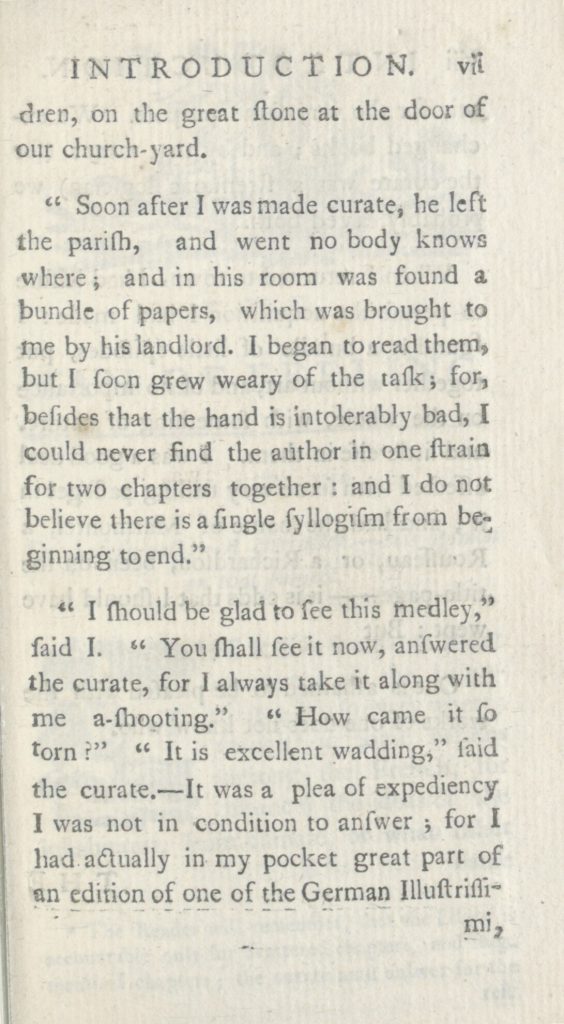

The sentimental novel relies on producing an emotional response from its readers and its characters. A mark of a reader’s sensibility was whether she was moved by the scenes of distress, reconciliation, poverty or hardship presented in the work. Though the sentimental novel usually expresses the values of the middle class, its stock characters, those its readers are to feel sympathy with, are often those lacking any agency in society such as the poor, elderly women, children and animals. Mackenzie employs many of the typical scenes of the sentimental novel but Harley, the man of feeling of the title with his excessive sensibility, is an aristocrat, albeit a minor one on a relatively meagre income of £250 a year. In creating a character more in line with his own upbringing, Mackenzie gave Harley, and sentimentality, a level of respectability and set up a background for him that allowed Mackenzie to address themes of loss and degeneration as Harley’s conservative world view of a paternalistic aristocracy is overtaken by a rapidly expanding commercial society exploited by cunning, duplicitous characters in pursuit of wealth and luxury. Another trope of the sentimental novel employed by Mackenzie is the fragmentary nature of the work that allows gaps and absences to appear. The novel is not a tightly plotted story with character development and a rounded conclusion but rather a series of vignettes such as those described above that were designed to provoke an emotional response in the sentimental reader. The narrative is presented through a found manuscript which is already fragmented as its previous owner, a curate, found it to be

“a bundle of little episodes, put together without art, and of no importance on the whole, with something of nature, and little else in them. I was a good deal affected with some trifling passages in it; and had the name of a Marmontel or a Richardson, been on the title-page— ‘tis odds that I should have wept: But One is ashamed to be pleased with the works of one knows not whom.”

Such is the curate’s disinterest that he has torn up much of the manuscript for gun wadding. Therefore the reader begins with chapter 11 and further gaps between chapters occur that allow Mackenzie to drop Harley directly into a scene without having to account for how he got there.

Mackenzie was at the centre of what we now refer to as the Scottish Enlightenment. The Man of Feeling can be read as part of the sentimental novel’s engagement with that era’s enquiries into human nature: our motives for benevolent or selfish acts and a search for sociability at a time when society’s former bonds were fragmenting as a result of specialisation and commercialism. Society’s increasing specialisation was a subject of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776) and before that his The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) questioned what became a theme of Mackenzie’s novel: “this extreme sympathy with misfortunes”, which, if such sympathy could be attained, “could serve no other purpose than to render miserable the person who possessed it.” Harley does spend much of the novel in a miserable state suggesting that Mackenzie, in line with Smith’s view of extreme sympathy, was not using his novel to promote a realistic mode of conduct that could establish social harmony. Despite his own ideas about being a good judge of character, Harley is consistently shown to be incapable of interpreting the modern world.

Sentimental novels were usually aimed at a female readership, though were fashionable enough for Robert Burns to describe The Man of Feeling as “a book I prize next to the Bible” in a letter of 15 January 1783 to his former tutor John Murdoch. In praising other sentimental novels, he continued that “these are the glorious models after which I endeavour to form my conduct”. However, he was also wary of the effect the novel may have on a young man about to make his way in society, writing to Mrs Frances Dunlop on 10 April 1790 that, “I do not know if they are the fittest reading for a young Man … There may be a pureness, a tenderness, a dignity … which are of no use, nay in some degree, absolutely disqualifying, for the truly important business of making a man’s way into life.” It was a commonly held view that too much sentimentality left a man without the means to make a success of himself in life.

The novel establishes a number of conflicts for the reader. There is a sense that Mackenzie is trying to show that if all of society were as sympathetic to others as Harley is then the world would be a better place. However, Harley is an ineffectual model whose own naivety when interacting with the commercial world shows him to be outmoded. Though not as wealthy as many of the nouveaux riches who are supplanting his kind, Harley is still able to live a life of relative leisure and has the time and the disposable income to spend on those unfortunates who populate the scenes of the novel. Is Harley acting selflessly by providing those in distress with money or is his involvement in their lives another form of entertainment in the commercial age? By extension does the reader also vicariously take part in this voyeuristic look into the lives of those less fortunate than themselves, or, does their entertainment come from the feeling that they are more worldly-wise than the gullible Harley and can easily see through the ruses that deceive him. Should Harley be praised for his benevolence or derided as a fool?

Some scenes within the novel were considered worthy of inclusion in compilations such as The Literary Miscellany; or, elegant selections of the most admired fugitive pieces, and extracts from works of the greatest merit, published in Manchester from 1794-1797 but by the 19th century the overly sentimental began to seem melodramatic and the novel’s frequent reference to tears and weeping had become a source for tears of laughter rather than sentiment. The change in fashion is perhaps no more marked than in two observations by Lady Louisa Stuart who as a 14 year old “had a secret dread I should not cry enough to gain the credit of proper sensibility” but in 1826, reflecting on the effect the novel had when read aloud in a group, wrote

“I, who was the reader, had not seen it for many years. The rest did not know it at all. I am afraid I perceived a sad change in it, or myself, which was worse, and the effect altogether failed. Nobody cried, and at some passages, the touches that I used to think so exquisite – oh dear! They laughed … Yet I remember so well its first publication, my mother and sisters crying over it, dwelling on it with rapture.”

Wilfred Partington (editor), The Private Letter-Books of Sir Walter Scott (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1930), p. 273.

By the late 19th century reading tastes had changed so much that an edition appeared that included an Index to Tears highlighting what were, by that time, seen as excessively sentimental scenes. An odd footnote to the history of The Man of Feeling illustrates the appeal of sensibility that the novel did so much to promote. Mackenzie had published the novel anonymously and six years later in 1777 there appeared an ‘An Elegiac Ode, to the Memory of Rev. Charles Stewart Eccles’, that attributed The Man of Feeling to Eccles, an Irish clergyman living at Bath. Found amongst Eccles belongings was a manuscript of the text, complete with annotations, crossings-out etc. that made it appear that he was the author. Eccles had died in a tragic manner, drowned while trying to save a boy from the River Avon, and the publisher of the poem wrote to Henry Mackenzie suggesting that, in the end, Eccles proved himself to be a man of feeling.

Further reading:

There are several editions of The Man of Feeling available from the Library’s website

You can read more about Mackenzie in the Biographical dictionary of eminent Scotsmen