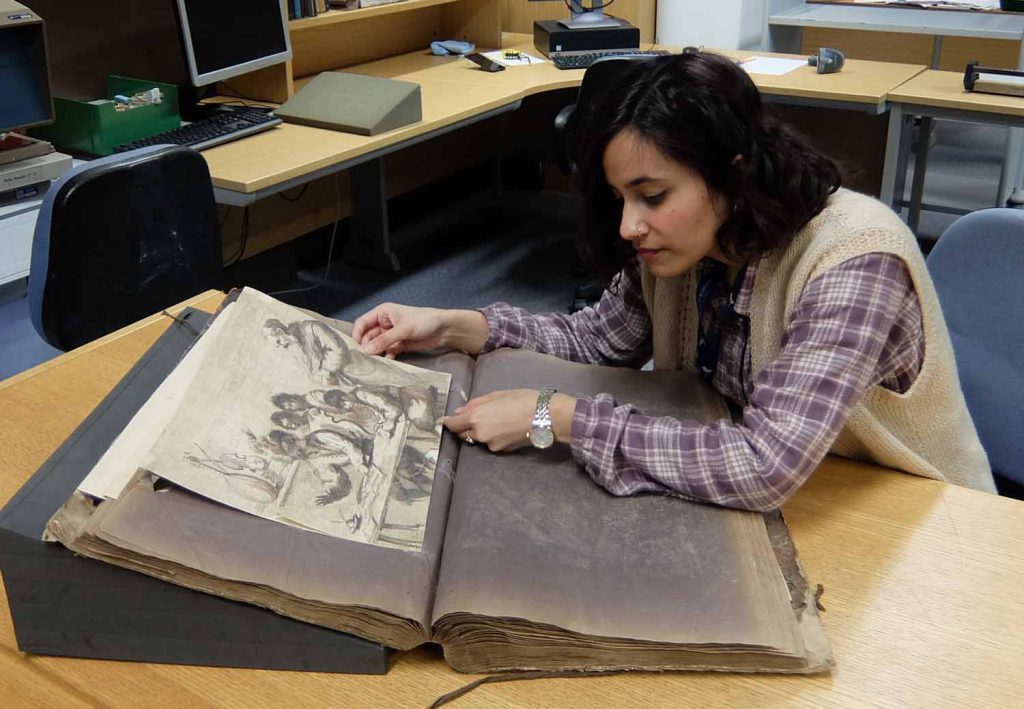

Hello, my name is Nava Rizvi. I’m a postgraduate Intern in Rare Books Collections and undertook this work as part of my MSc. (History of Art, Theory and Display) at the University of Edinburgh. My main task has been to research and catalogue etchings and engravings held within the Newhailes Collection. Most of them date back to the time of Sir David Dalrymple (1726-92), Lord Hailes, the Edinburgh judge and historian. The collection contains many hundreds of etching and engraving prints that range in subject from landscapes and topographical representations to portraits, genre scenes, Biblical depictions as well as anatomical and artistic studies.

Upon sifting through the vast collection of prints within the Newhailes Collection, there was a set of four, most likely part of a series, that instantly caught my eye.

The were all by Claude Mellan (1598-1688), an engraver and painter most active in Rome and Paris. Arranged within the portfolio (shelfmark: Nha.EL.58) in a grid structure, these prints portray representations of various figures from the Old Testament and the Apocrypha.

A representation of Lot surrounded by his two daughters, seated, while holding a goblet of wine in his hand.

_______

Samson resting his head in Delilah’s lap as she cuts his hair. Delilah discovered that Samson, an Israelite judge and an opponent of the Philistines, received his power due to his uncut hair. She was known as Samson’s best-known lover, but perhaps also his betrayer.

_______

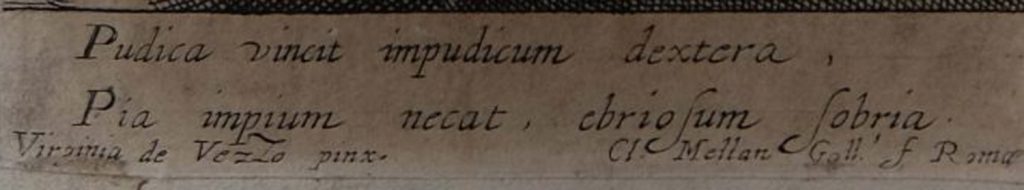

A portrayal of Judith, the Jewish heroine, holding a sword and leaning against Holofernes’ head – the Assyrian general of Nebuchadrezzar, that became known to be murdered by Judith.

_______

Herodias holding the head of John the Baptist on a plate.

In addition to being beautiful, these four prints especially attracted my attention because of their female representation, that for once, was not necessarily stylised and depicted catering to the male gaze. The portrayals of these both antagonistic and protagonistic female figures exudes an aura of vigour which simultaneously encompasses their femininity through domestic settings rather than being visually objectified and highly sexualised.

Inscriptions at the foot of each of the prints gives information on their production. Although they seem as if they could be part of a series by Claude Mellan, with similar stylistic depictions throughout, they were based upon original works by Mellan and two other artists. The engravings of “Lot with his two daughters” and “Samson resting his head in Delilah’s lap” were after Mellan’s own paintings. The depiction of “Herodias holding the head of John the Baptist” was after an artwork by Simon Vouet (1590-1649). The inscription that most caught my eye was for the engraving of “Judith” (lower left of the grid) which was engraved by Mellan after a painting by the Italian artist Virginia da Vezzo (1600-1638).

Virginia da Vezzo was a female painter and draughtswoman from Velletri, Italy. When her family moved to Rome, she enrolled in a painting workshop, and eventually became a qualified painter coming out of the Accademia di San Luca. In 1626, da Vezzo married the French painter Simon Vouet and moved to Paris to live with him, which is also where she died. Being surrounded by painters, it was inevitable that she became a muse for many at that time. As I dug deeper in the hopes to find more about a female painter, I encountered not much other than numerous portraits of her in which she is typically referred to as ‘Virginia da Vezzo – Wife of Simon Vouet’.

The print after da Vezzo portrays a portrait of Judith holding a sword, with her head tilted to the left, looking away. Although the visual aspects are mostly similar in all the engravings, it seems as if the heroic portrait of Judith and her role is visualised in a rather passive manner, looking away despite being depicted as a saviour, as opposed to the rest of the prints where the antagonist female figures are more actively involved within their roles while interacting with their subjects.

This inclusion of this print raises questions as to why this the only work based upon an original by a female artist, when most of the prints likely fall under the same series? Was there a gap or potential error? One wonders whether the visual aspects and the roles depicted would have been different if they had all been made by the same female artist? Moreover, to come across the only female artist while sifting through portfolios of hundreds of etchings and engravings makes one wonder how many more female artists could there have actually been? Finding answers to these questions are ongoing as contemporary scholarship in art history aims to reexamine and rewrite the discourse from a feminist perspective. This new direction in art research strives to not only be more inclusive of women artists of their time, but also to critically analyse the representation of female figures independent of the male gaze. In the context of these ongoing efforts, I was fortunate to have come across these prints and the work of Virginia da Vezzo. Highlighting them is, perhaps, my humble attempt at relooking, adding to, and rewriting feminist art history.

Further reading:

Etching & Engraving: Techniques and the Modern Trend. John Buckland-Wright. (London: The Studio Publications, 1953). Shelfmark: SU.37 (3.7.2 Buc)

The Thames and Hudson Manual of Etching and Engraving. Walter Chamberlain. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1972). Shelfmark: HP2.92.1647

A Little Feminist History of Art. Charlotte Mullins. (London: Tate Publishing Ltd., 2019). Shelfmark: PB5.219.518/21

Feminist Theory. (London: SAGE Publications, 2000). Shelfmark: QJ4.1013 SER