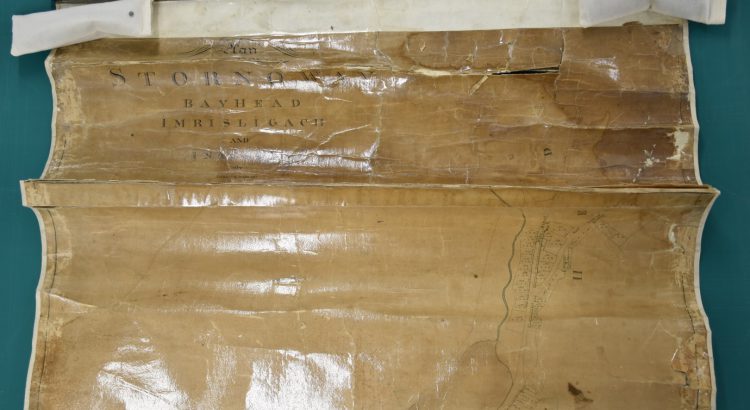

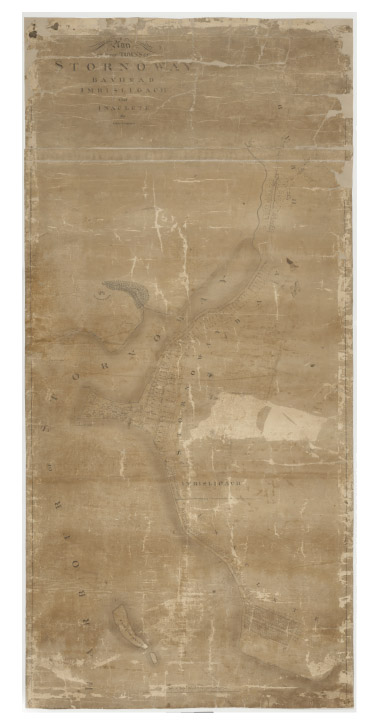

The Stornoway map is one of a group belonging to Stornoway Public Library, which were sent to the Library in 2017 for digitisation. However, the map could not initially be digitised due to its poor condition. It had been heavily conserved in the past, leaving the paper stained, skinned and distorted, with many large cracks, tears and losses. It had also been entirely covered in cellulose acetate lamination, making its surface very glossy. With funding from the Aurelius Trust, the Library was able to undertake the conservation work necessary for digitisation, and the conservation project began in September 2018. A description of the map and a treatment proposal were given in our Plans for the conservation treatment of the Stornoway Map blog post from October 2018.

This report is by Claire Thomson, Conservator, and describes the fascinating and intricate methods used to make this map newly accessible and able to be scanned.

Treatment undertaken

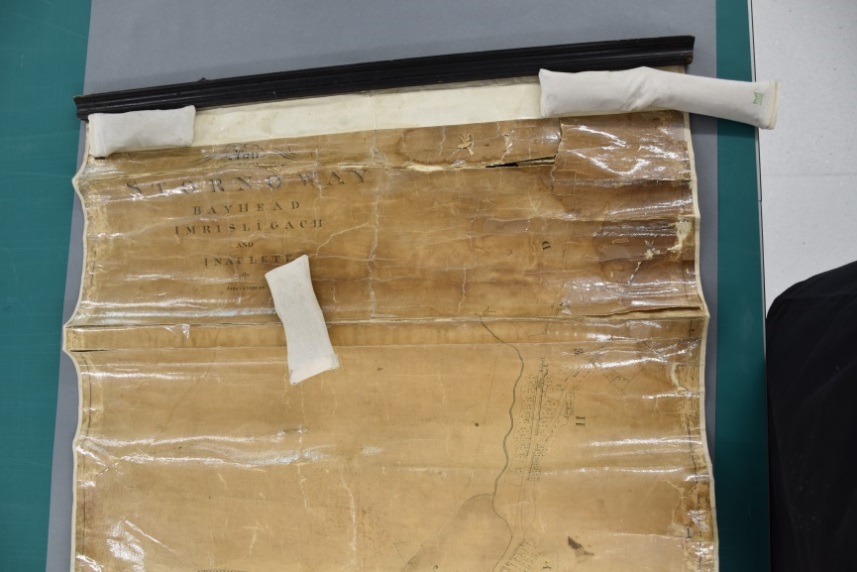

The map was firstly dry cleaned on the front and back, using a chemical sponge and a soft brush.The tacks were carefully removed from the wooden batons, taking care not to damage or puncture the map. The tacks and wooden batons were retained, to be returned to Stornoway alongside the map.

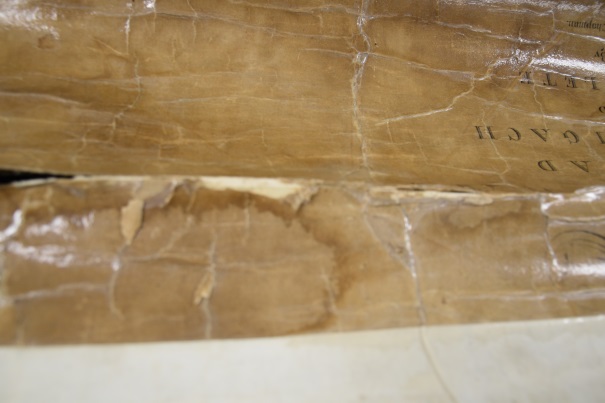

Detail showing how the wooden batons were tacked to the main body of the map

The cotton tape was carefully removed from the front and back of the map, and small fragments of the original tape were discovered underneath

Removing the original backing

The map was then turned over and the original linen backing was removed in strips, without the use of moisture. It came away fairly easily because the adhesive had largely failed, although there was some minor skinning of the reverse of the map.

the linen backing in strips

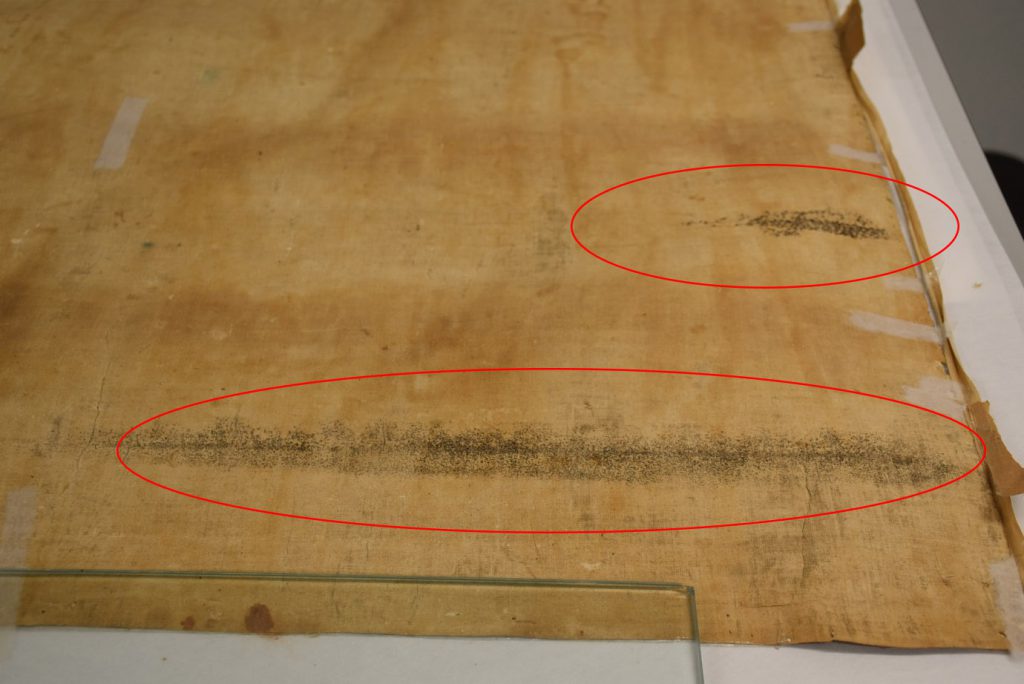

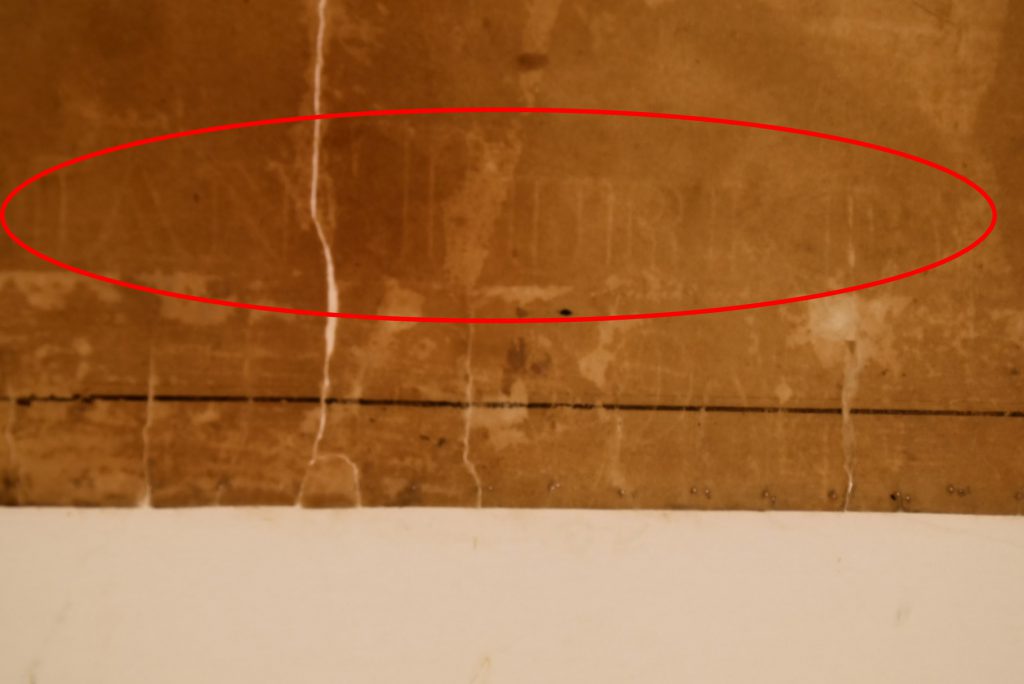

Following the removal of the linen backing, evidence of mould damage became visible on the bottom section of the map. Either water got inside the rolled map at some point, or the map was rolled the other way round and stored in a damp environment, so that the bottom section was outermost and most affected by the environment.

The top third of the map had a thick white paper backing applied in addition to the linen backing. The removal of the backing layers from this section was more challenging, because the paper primary support was very cracked. A poultice made with laponite clay was brushed onto the more stubborn areas and left for 10 minutes, after which it could be scraped off, taking the paper backing with it.

Temporary repairs

Some of the more fragile areas of the map were very weak once the backing had been removed, and were given temporary repairs using Japanese paper and wheat starch paste.

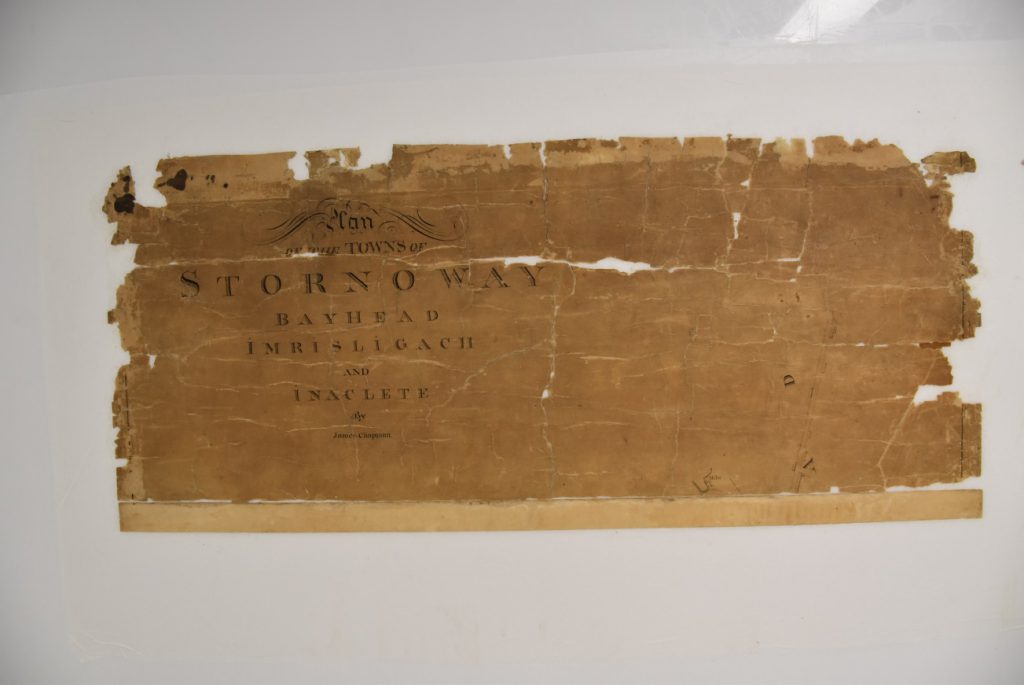

More of the map than before

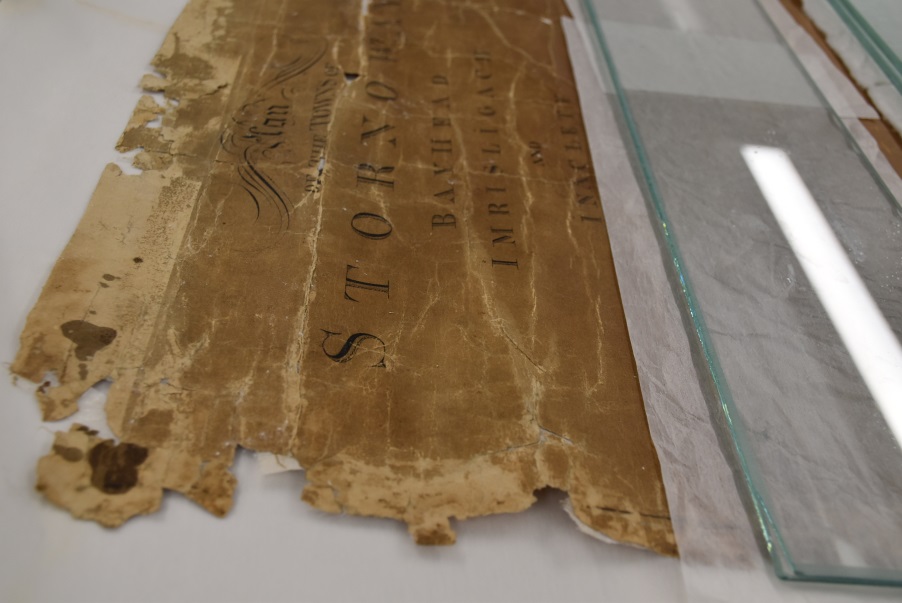

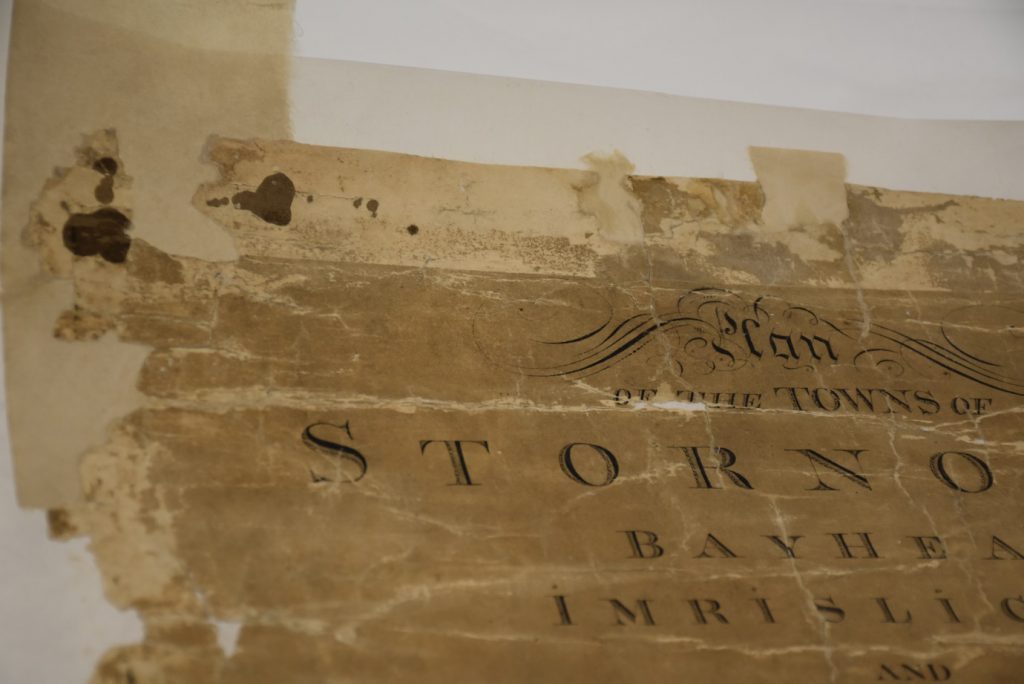

Following the removal of the lining, it became evident that there was slightly more of the map than had been visible previously. The top edge had been hidden by the folded over white paper backing. This edge was in very poor condition, which is probably why the decision had been made to cover it up.

Following the removal of the lining, the reverse of the map was cleaned using a smoke sponge. This removed some of the old adhesive, and it was anticipated that the remainder would be removed when the map was washed.

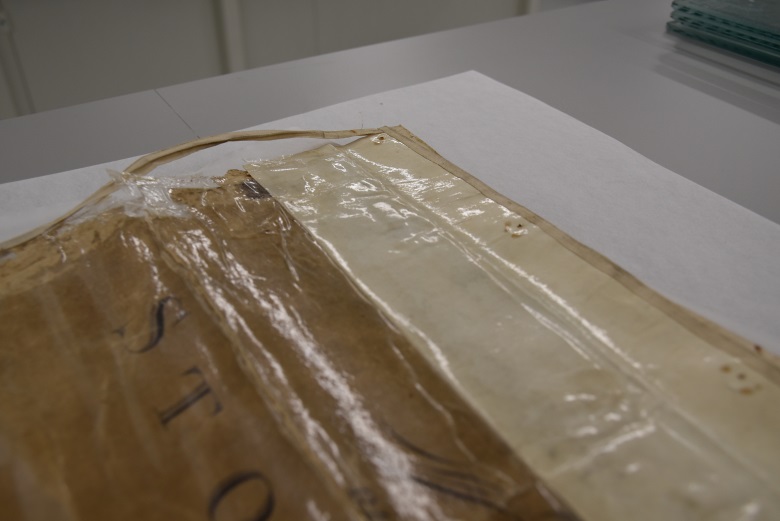

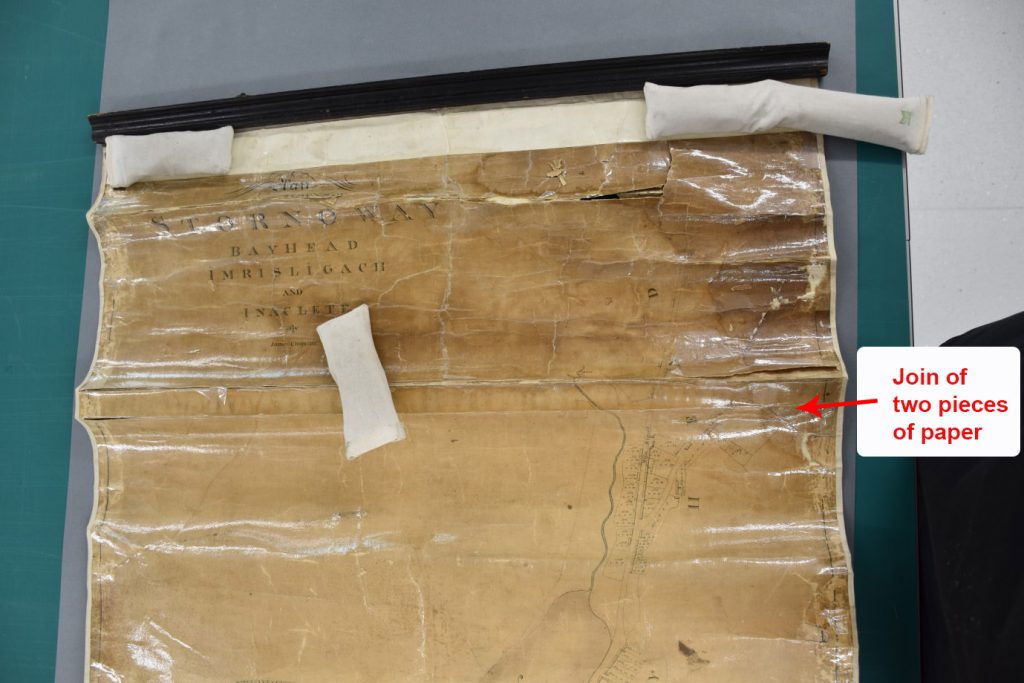

Removing the transparent plastic layer

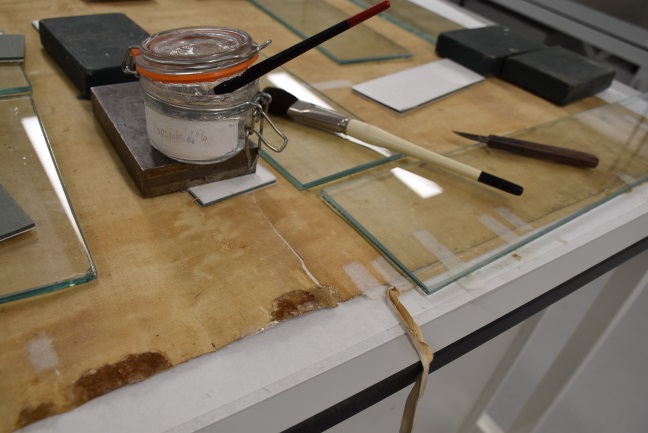

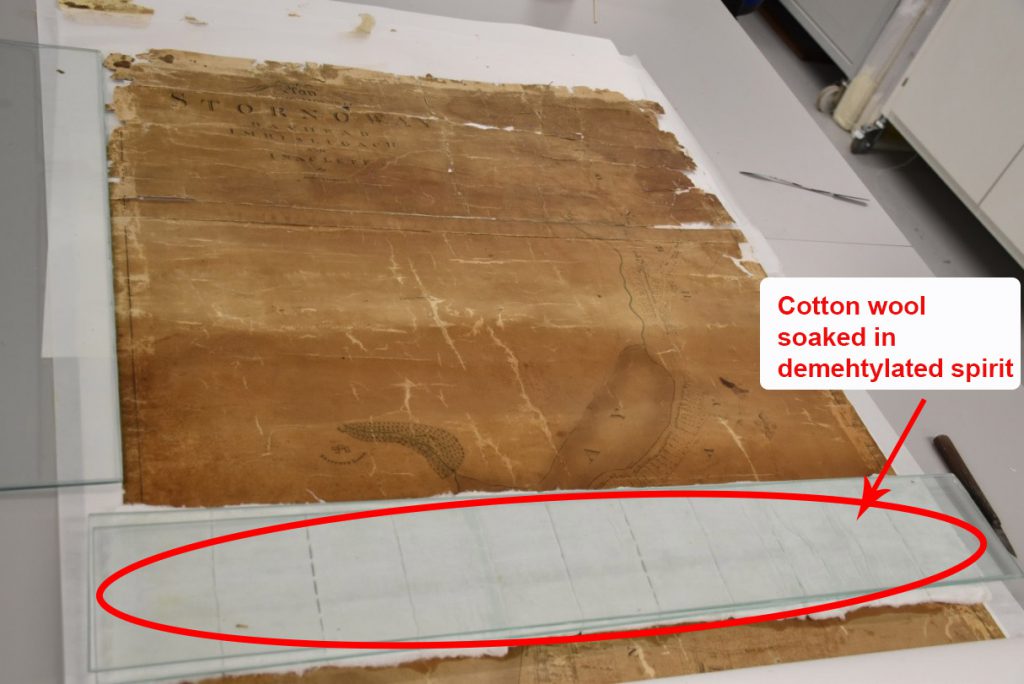

The transparent plastic layer of cellulose acetate which had been applied to the surface of the map was carefully removed dry using a fine spatula, and this worked well in most areas. However, in some places the plastic was more firmly adhered and hence harder to remove, and these areas seemed to occur fairly randomly across the map. For these areas a poultice of cotton wool soaked in denatured methylated spirit (DMS) was placed on top of the map for 5-10 minutes. This generally made the plastic easier to remove, although care was required to avoid removing the surface of the paper at the same time. In the places where the surface of the paper was prone to lifting, a mixture of 2% Klucel G and DMS was used to re-adhere it. This adhesive was chosen in preference to a water-based system because it would not dissolve away when the map was washed.

Removing surface adhesive

Following the removal of the plastic layer, traces of adhesive were left behind on the surface of the paper. This was removed with a poultice of cotton wool soaked in denatured methylated spirit (DMS), which was left for 10 minutes. It had been hoped that the poultice might also take away some of the old varnish, but the varnish was very deeply ingrained into the paper and could not be removed completely.

With the plastic and adhesive layers gone, it became apparent that the map was made up of two pieces of paper, which had not been obvious previously due to the complex layered structure. The join between the pieces would have been placed under considerable strain and was badly damaged.

Removing further stains and adhesive

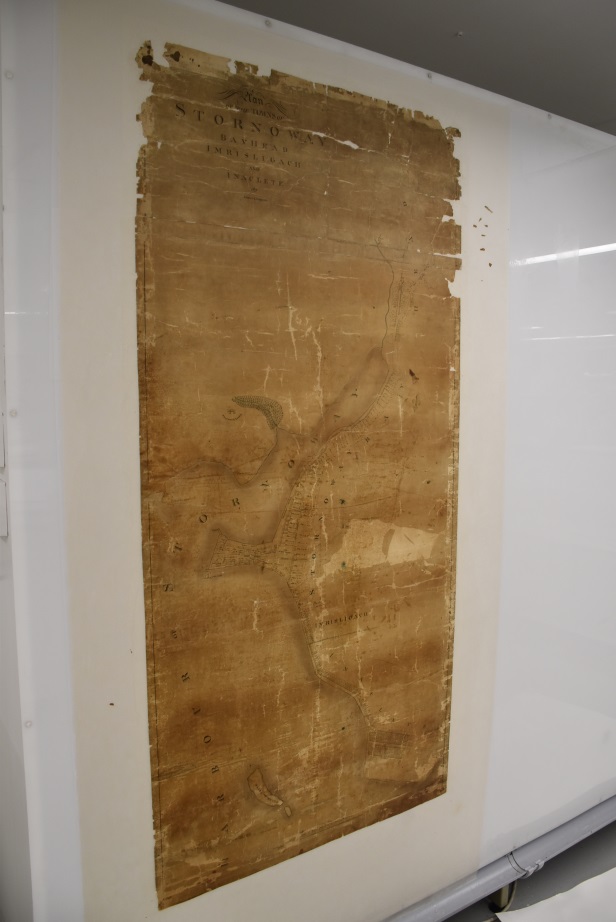

The map was then lightly humidified before being blotter washed. It was too fragile for immersion or float washing, and these methods might have caused the detachment of the temporary repairs. The washing did not remove any more of the varnish but it greatly reduced the staining on the map, particularly on the top section. It also removed the final fragments of old adhesive from the reverse.

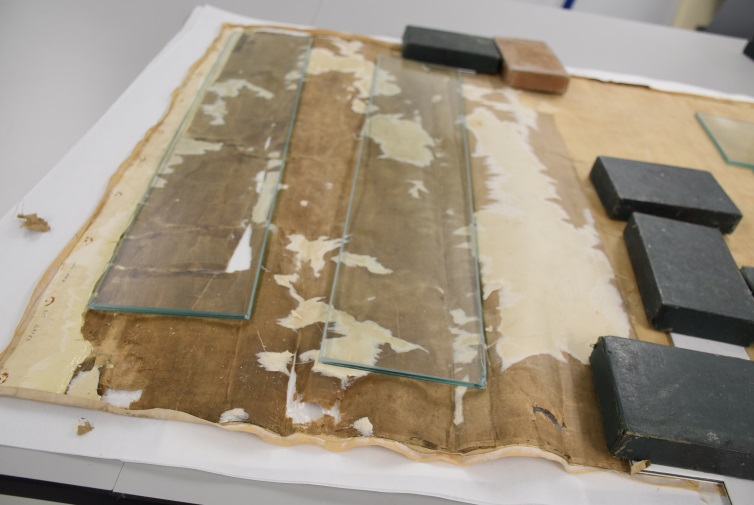

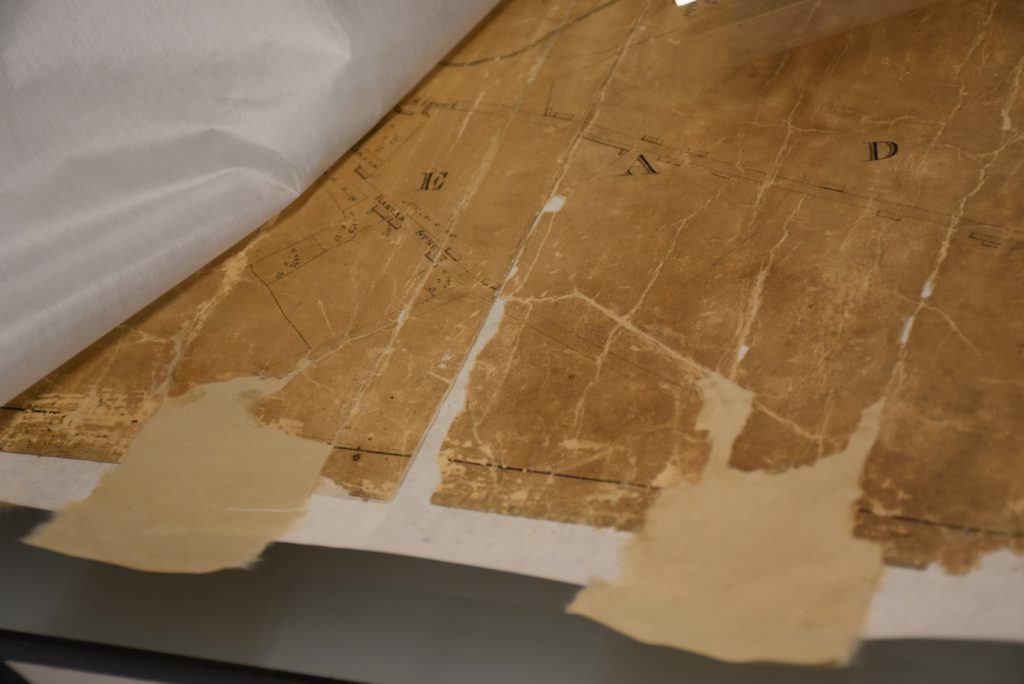

The washed map was then lined on spider tissue using wheat starch adhesive. This was done on a walled light box.

Discovery of the watermark

While the map was on the light box its watermark became apparent. It read JAMES WHATMAN TURKEY MILL KENT. Whatman was a high quality type of paper, and its use has undoubtedly facilitated the survival of the map.

Once the map had been dried and removed from the lightbox the tissue lining was trimmed round the edges, and then the map was humidified again before a second lining layer of machine made Japanese paper was applied on top of the spider tissue, for extra strength. As before, this was trimmed once it had completely dried.

The losses from the surface of the map were infilled using a toned, handmade Japanese paper. The damaged area at the join between the join of the two pieces of paper was reinforced using a fine strip of spider tissue.

The map was then humidified for the last time and left under weights for several days, after which it was loosely rolled, with an interleaving sheet of acid free rag end paper. The rolled map was wrapped in Tyvek, tied with cotton tape and placed inside a custom made phase box.

Conclusions

The treatment method largely followed the original proposal. It had been thought that it might be necessary to apply a temporary facing to the upper section of the map, but temporary repairs sufficed instead. Additional information about the map, such as that it was made from two sheets of paper and had a WHATMAN watermark, was obtained during the treatment. It was frustrating that not all of the varnish could be removed, but the staining was reduced dramatically, and the overall appearance and stability of the map was vastly improved by the treatment. The primary aim of the treatment was to allow the map to be digitized, and this is now possible.

Claire Thomson, Conservator, National Library of Scotland

A zoomable image of the map can be viewed at: https://geo.nls.uk/mapdata3/189530621_1/openlayers.html

The map will appear in a new online gallery of historical maps of Stornoway, under development, which we hope to publicise in the Spring.

We are grateful to the Aurelius Trust for kindly funding the conservation work on this plan.