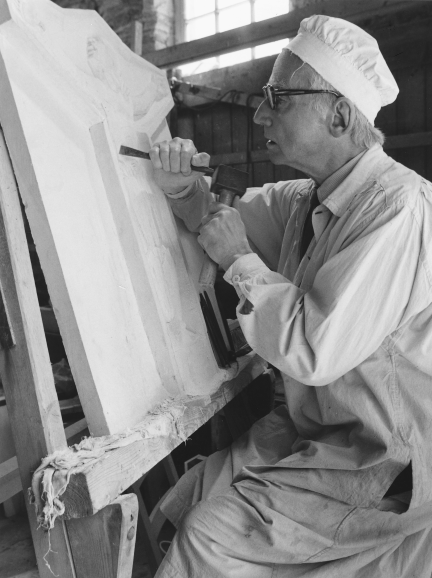

“While he chips away with his chisel the rest of the work on the building goes on round him. The rickety noise of cranes. The sharp rattle of drills. The clattering of bricks. And the clang of steel girders…”

– The Edinburgh Evening Dispatch, 14th July, 1954.

For several months in 1954 and 1955, the front of the new Library’s facade was shrouded in scaffold and canvas shields. Unbeknownst to passers by, behind the screens examples of work by some of Scotland’s most respected sculptors and masons were being installed. Through the mass of scaffolding, and at the end of two flights of ladders, a cloth-capped sculptor was often seen carving away at seven large blocks of stone protruding from the front of the building. This was the Chief Sculptor of the National Library project, Hew Lorimer.

Lorimer hailed from a family with a history of artistic endeavours – his father, Sir Robert Lorimer, was one of the pre-eminent Scottish architects and furniture designers of the early 20th-Century, while his uncle, John Henry Lorimer, was a respected painter. Educated at Loretto School in Musselburgh, Hew Lorimer spent an unhappy year at Oxford University before returning to Edinburgh to enter the School of Architecture at Edinburgh College of Art. The sudden death of his father in 1929 ended the arrangement for him to take up a position at his father’s office, and so he instead took up a course in Design and Sculpture under Alexander Carrick at the College of Art. Completing his diploma in 1934, Lorimer won a Grant Bequest Scholarship which would fund two years travel and experience at other sculptors’ studios. He elected to spend time at the Pigotts studio of Eric Gill in Buckinghamshire and it was here where Lorimer honed his skills. Being left-handed gave Lorimer some disadvantages, but Gill described his work under him as “very decent”, which was apparently as high praise as one could expect from Gill. Returning to Scotland after touring France, Lorimer built a reputation for producing high-quality stone sculptors; under the tutelage of Carrick and Gill, he preferred the ‘direct carving’-method and referred to himself as a “stonecarver”, while his faith often steered him towards the subjects of his works.

Hew Lorimer first became involved with the National Library project following the Second World War, largely through his friendship with the Library’s architect, Reginald Fairlie.

Fairlie had been educated in a Catholic Oratory in Birmingham and had never attended any formal artistic education prior to obtaining a post in the offices of Hew’s father, Sir Robert Lorimer, in 1901. During his time learning under Robert Lorimer, Fairlie would have a fraught relationship with him; a talented draughtsman, Fairlie was unconvinced by the need for formal classes and examinations – Sir Robert, in turn, accused him of being lazy, assuring him he would never make a career as an architect. Though he did not get on with his father, Fairlie would form a close friendship with Hew Lorimer and, following Sir Robert’s death in 1929, offered him support and encouragement in his career as a sculptor, as well as opportunities for the pair to collaborate together on a number of projects.

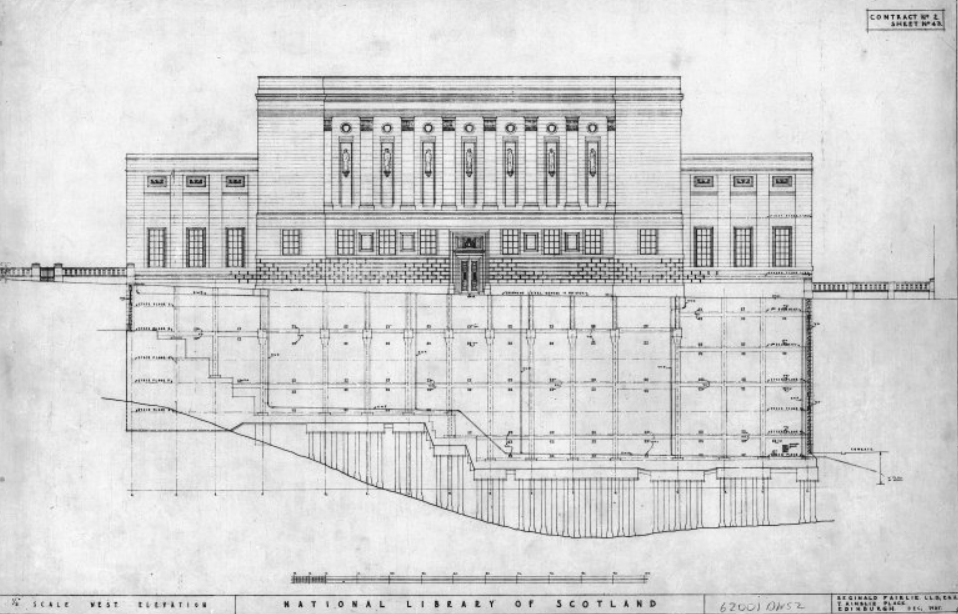

From 1925, Fairlie had run his practice from his home at 7 Ainslie Place, Edinburgh, with his work mostly centred around Churches, memorials, and country houses. Fairlie’s designs were often simple but he would try to enhance them by incorporating work from independent craftsmen. With major work resuming on the Library building in 1950, Lorimer and Fairlie had discussed sculptures for the National Library building over several months. Although Fairlie said it would be up to the Ministry of Works and the Board of Trustees to formally make the appointment, he clearly wanted his friend to be in charge of these sculptures. Fairlie’s library design was in a classical idiom, but it was not based on classic proportions; as such, the architect felt that any sculptures, as well as enriching the facade, would enhance the scale of the building and give added importance to its central block.

Unfortunately, Fairlie did not live to see the Library completed. Having served with the Royal Engineers during the First World War, he had returned from the Western Front in less than robust health; also, among his many eccentricities were his habits of always walking everywhere and of camping outdoors to see the sites of proposed projects at dawn’s first light. These had combined to leave him with a persistent cough. With his health deteriorating, he was moved into St Raphael’s nursing home, Edinburgh, where he died in October 1952. Reginald Fairlie was laid to rest in the family plot of the Eastern Cemetery by The Pends in St Andrews, Fife, for which Hew Lorimer carved a new ornate monumental stone.

On 20th April 1953, the Ministry of Works wrote to the Library concerning the sculptures Fairlie had proposed prior to his death:

“It was the intention of the late Dr. Fairlie to nominate as sculptor for the figures Mr. Hew Lorimer, A.R.S.A., with whom he had discussions at various times. Mr. Conlon has now written formally asking for approval on this course. The Ministry for its part is prepared to agree.. The Ministry is informed that Mr Lorimer, following the discussions with Dr. Fairlie, proposed that seven symbolic figures should depict the following subjects: Arts; History; Law; Creative art of writing (the central figure); Theology; Science; and Medicine.”

The Ministry of Works added that, “Mr Lorimer would appoint one or, if necessary, more sculptors to carry out other decorative work on the façade, under his supervision”. Following his formal appointment, Lorimer assembled a team of skilled sculptors to complete the decorative work on the façade of the building. His principal collaborators at the Library were:

- James Barr was born in Rinning Park, Glasgow, and, though he had left Bellahouston Academy with few qualifications, he was particularly talented at art. Whilst working in the Govan shipyards, Barr enjoyed evening art classes and he became an assistant in the studio of Benno Schotz, an Estonian sculptor who would later become the Glasgow School of Art’s Head of Sculpture. His interest and talent led him to enroll as a Student at the School, where he learned under Archibald Dawson. Barr’s prowess was reflected in the number of scholarships he was awarded and he eventually became a member of the School’s staff. During the Second World War, he worked as a riveter but returned to the School of Art in 1945, where he would hold a number of positions. Regularly exhibiting work at the Royal Scottish Academy, Barr became an Associate Member of the Royal Scottish Academy and an Associate Member of the Society of British Sculptors.

- Elizabeth Strachan Dempster was born in Greenock, but moved to Edinburgh when orphaned to live with her guardian, Dr Charles Warr of St Giles Cathedral. She attended Edinburgh College of Art, where she studied sculpture alongside Hew Lorimer. Dempster also studied in London and Munich, and in 1938 received her first major commission from the Clyde Navigation Trust for a sculpture as part of their contribution to the Empire Exhibition at Bellahouston Park. Basing herself in Edinburgh – with a studio on Belford Road – she would later produce work for St Giles’ Cathedral and the Royal Scots Memorial in Princes Street Gardens.

- Scott Sutherland hailed from Caithness and was another alumni of Edinburgh College of Art. Securing Travelling Scholarships enabled him to continue his studies abroad, and he was able to travel round the Mediterranean (to Egypt, Greece and Italy) and later to France and Germany. Like Dempster, Sutherland provided sculptures for the 1938 Empire Exhibition before his career was interrupted by the Second World War, during which he served in the Royal Artillery. Following the Second World War, he first taught at Belfast Technical College, and then sculpture at Dundee College of Art from 1947 onwards. With his father having served in the First World War and with his own wartime experiences, Sutherland was often drawn to military subjects. His most significant work was the Commando Memorial at Achnacarry, which was unveiled in 1952.

- Maxwell Allan was an Edinburgh-based decorative sculptor. Having worked on Dunfermline Abbey and Edinburgh’s Robin Chapel, Allan had also collaborated with Hew Lorimer on several projects. After working at the National Library, the pair later embarked on their most famous project, the colossal statue Our Lady of the Isles on South Uist – a 27 foot-high statue carved from nine blocks of granite which was formally unveiled in 1956.

Although relatively windowless, the Library’s facade would not be without decoration – Fairlie had deliberately left parts of the facade uncluttered so as to allow for sculptural decoration to be added at a later date. This was similar to the project Fairlie and Lorimer had worked on together at St. Margaret’s Church in Dunfermline, where Fairlie’s design of the building allowed Lorimer the opportunity to create a grand reredos dominated by four saintly statues. Lorimer would create a similar arrangement for the Library’s facade but on a much grander scale.

Lorimer only gave Barr, Sutherland and Allan limited direction, “to each simply suggesting by sketches the themes and leaving them to work them out in the actual process of carving to one-quarter scale”. As the proposed reliefs above Lorimer’s statues required a more “imaginative treatment”, Elizabeth Dempster was given complete freedom. To see their work on the Library’s facade, you have to look up:

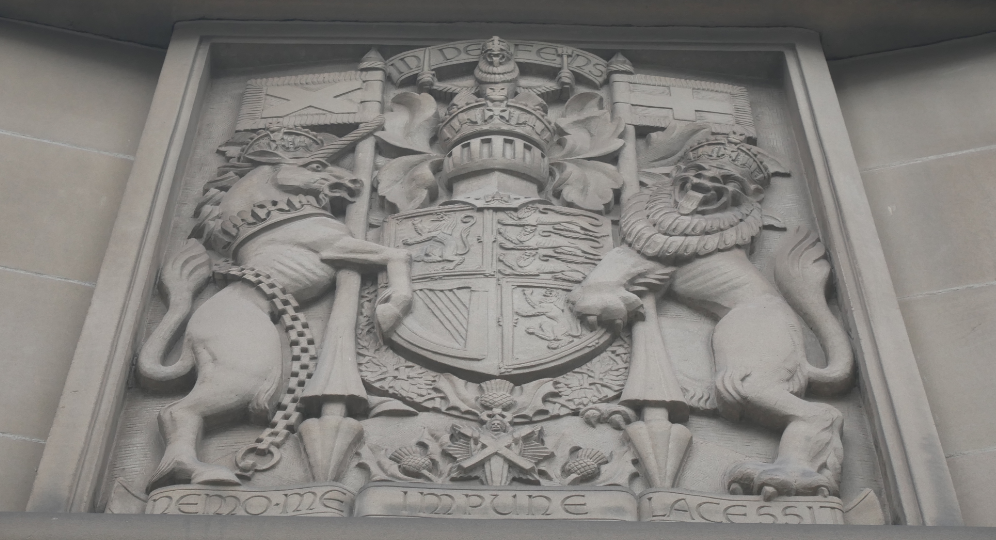

- Above the main entrance door is the Royal Coat of Arms, sculpted by Scott Sutherland.

- Carved by James Barr, the figurative panels on the end blocks represent various arts and methods of communication, “in which ideas – the raw material of writing – are transmitted to the minds of man” – on the North wing (from north to south) the panels represent Fingerspelling, Learning, and Braille, while on the South wing (From north to south) they present Writing, Revelation (or Thinking), and Carving/Sculpting.

- On the North and South elevations of the Library building there are decorative panels by Maxwell Allan;

- Above the seven statues are figurative rondelles, carved by Elizabeth Dempster.

The seven allegorical figures were designed by Hew Lorimer himself, each representing a different discipline. While working on the figures, Lorimer decided they should be designed so as to “reiterate the rhythmic pattern of the whole facade”. He later described the designs he carved:

Medicine, flanking science, is represented by an Aeschylapien figure: he holds at his right side the thyrsus and in his left hand a pot of ointment, symbolic respectively of the subltlety and cunning of diagnosis and prescription and of healing.

Balancing Theology on the right of History stands Science; also on an orb, his mind and hands wholly concentrated in solving the mystery of Matter – and it will be observed that, in this Atomic Age, the rays of his perceptive intelligence have penetrated to its very core.

History – as old time – holding in one hand a partially unfolded scroll and in the other a quill pen symbolising the sense of chronology and the capacity to record.

The Poetic Muse – a female figure, mysterious yet innocent. The austerity of her attitude disturbed only by the gesture in which she offers the secrets of the magic of the poetic art.

Justice, whose authority is given for the definition of that mean point between good and evil called “justice”; hence his uncompromisingly extended right arm and pointing index finger. In his left hand he grips with great firmness the work on which all subsequent Scottish Jurisprudence has been built, Stair’s Institutions.

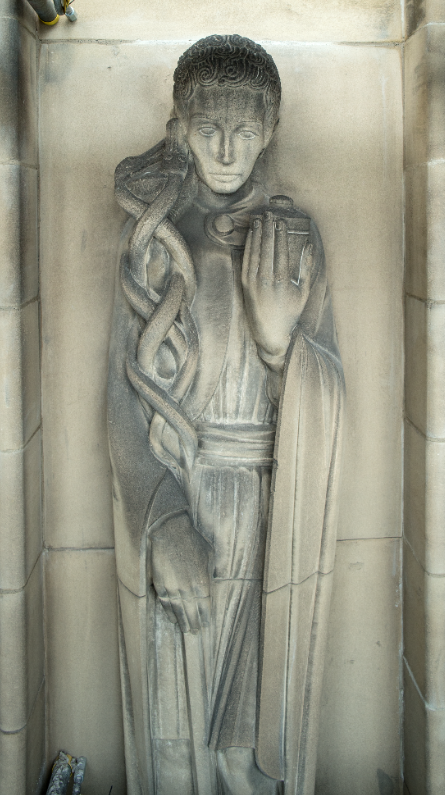

Theology, from whom all administrators of the Law may learn to temper justice with mercy. Theology is represented as Guardian of the Sword of the Spirit and Word of God. He stands upon an orb impressed with the symbol of the Cross, out of which grows the vine rising towards and entwining the Sword of the Word.

The Arts represented by Music and, as perhaps the most abstract and heavenly of them, he stands in proximity to Theology.

Each of the sculptors used their own skills and methods to complete their work. For example, whereas Lorimer always worked from his own sketched designs and carved direct onto stone without using scale models for reference, Barr appears to have first produced miniatures of what his final designs would be. Two of the original models Barr used – those representing Signing and Braille – survive to this day and have recently been added to the Scottish Design Galleries at the new V&A Dundee.

As the sculptor’s work was slowly revealed, it caught the attention of pedestrians and visitors to the Library. Towards the end of the National Library project, Mr William Beattie – the then National Librarian – wrote to Lorimer regarding some feedback he had received from a visitor to the Library:

“[He] was in my room today and, as a working mason, was very critical of the panel in which carving on stone is represented. He says that the square-headed hammer might be used for granite but not for freestone and that, even on granite, it could be held for only a few minutes and then only to do some of the deeper cutting, as its weight would be 6 or 8lbs, much more than that of the usual wooden mell! Also that a man holding the hammer in his right hand would work from the right and not the left and that the thumb should be not straight but quite loosely curved round the chisel! However, he added that he was being pedantic and that he liked all the panels very much.”

Lorimer responded to Beattie that he was “fascinated” by these observations; however, in defence of Barr’s depiction of the use of a hammer in the panel, Lorimer opined that if the critic had:

“stepped up the ladders to where work was going on (in my absence) he would have found that every carver there was using square-headed hammers which certainly do not weigh 6 or 8lbs. He would also soon have witnessed that we hold our hammers for hours rather than minutes at a time. The position of the Child was dictated by design and by the fact that it is in relief. When cutting lettering (as in the panel) the thumb, for greater comfort of the chisel is held stiff… Letter cutting as taught by my Mr Allan and at Edinburgh and Glasgow Schools of Art is invariably in freestone and 2lb square-headed hammers are ‘de rigeur’… sometimes the striking area of the ends are filed down to no more than an inch square or less! They seldom weigh more than 4lbs.”

In conclusion, Lorimer said he was glad that the critic’s “‘pedantry’ did not destroy his liking of the panels”!

Lorimer was clearly proud of the work he and his colleagues had contributed towards the Library project, and wanted it all to be seen as part of an “architectonic unity”:

“carried through to the wings by a series of panels by James Barr and Maxwell Allan, of which the six of the main façade, by the former, represent several ways in which ideas (of which books are the repositories) are communicated. As the sculptor in charge, it fell to me to decide what form this element in the architectural scheme should take. The idea of the great comprehensive encyclopaedic library is a legacy from the Age and the Ideal of Humanism. The building is clearly one more expression of the Architecture of Humanism. The sculptures thus, I felt, must conform and express something of the recollected quality of high thinking, and yet, since it is a ‘National Library’ and therefore ‘ours’, must say something to the man in the street. Accordingly, ‘attributes’ were either appropriated or devised such as would give a clue to the identity of each figure and their heads were lowered so that their eyes might meet those of the passer-by. Learning and the communication of ideas begins in earliest childhood and consists also of child learning from child by example of emulation. So, in the wings of the Library we have represented those beginnings in children of what may culminate in the kind of adult study that is provided for in such a Library. The four panels on the north and south ends are variations, by Maxwell Allan, on the foliated theme of the aforementioned panels.“

The sculptors completed their work despite pressing time constraints – all the carving was done in situ and so they were not allowed to begin until the walls and roof of the Library were structurally secure. Nevertheless, the limited time available led to complete trust in the delegation of work among the sculptors. Indeed, Hew Lorimer later admitted that:

“ I had no time, even if I had wished to, to interfere as chief sculptors tend to do, and consequently the work went ahead without crises or recriminations and we all parted good friends.”

Acknowledgements: Images kindly supplied by the National Library of Scotland and Historic Environment Scotland/SCRAN.

‘Justice’ by Elizabeth Dempster.