“Whatever may be the success of my stories, I shall be resolute in preserving my incognito, having observed that a nom de plume secures all the advantages without the disagreeables of reputation.” George Eliot

The author Mary Ann Evans (1819-1880) is better known as George Eliot. In 2020 when the ‘Reclaim Her Name’ project published the first edition of ‘Middlemarch’ to appear under the name Mary Ann Evans, rather than George Eliot, it drew criticism. The project was designed to highlight how women have historically used pseudonyms to avoid gender bias, but in the case of Eliot her own intentions seemed to have been overlooked. The Chair of the George Eliot Fellowship commented:

“They did not grasp that George Eliot chose that name and chose to retain it, as was her right, and that her integrity as a writer and her own feelings about herself as a writer are bound up in what she called herself.”

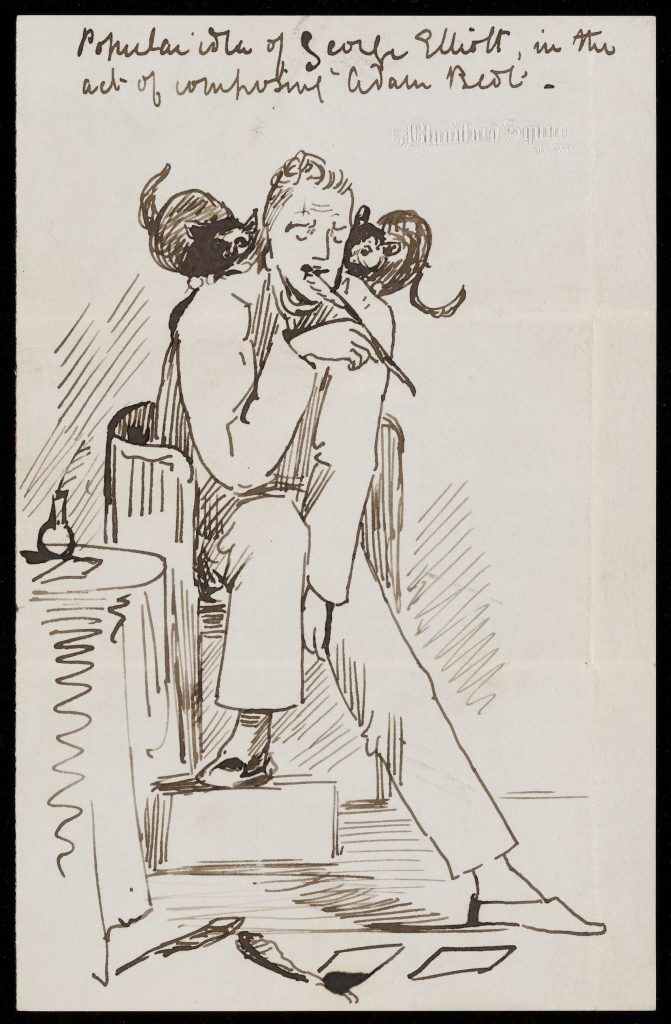

The success of Evans’ second book, the novel ‘Adam Bede’ published in February 1859 had increased speculation about its authorship. The previous year a collection of Evans’ stories ‘Scenes of Clerical Life’, first published anonymously in ‘Blackwood’s Magazine’, had been issued under the pseudonym George Eliot.

‘Blackwood’s Magazine’ (founded in 1817 by Edinburgh publisher William Blackwood) was a respected literary journal for a middle-class family readership. John Blackwood, Evans’ editor, entered the family business in 1840 and was involved in setting up the firm’s London office in Pall Mall, before returning north to Edinburgh to take over the editorship of the magazine. Blackwood did not know the real identity of the author of ‘Scenes’ until 1858, although he guessed it was Mary Ann Evans because Blackwood’s communication with Eliot was initially through Evans’ partner George Henry Lewes.

Today Evans’ and Lewes’ letters to Blackwood are preserved in the papers of William Blackwood & Sons at the Library, and these offer fascinating insights into the publication of her works. In a letter of 10 April 1859 to Blackwood (signed ‘George Eliot’), Evans sent an extract from a letter from an old friend in Warwickshire, which she thought would amuse her publisher. Evans’ correspondent claimed that the novelist George Eliot was a man called Mr Liggins:

“The son of a baker, of no mark at all in his town, so that it is possible you may not have heard of him. You know he calls himself ‘George Eliot.’ It sounds strange to hear the Westminster [Gazette] doubting whether he is a woman, when here he is so well known. But I am glad it has mentioned him. They say he gets no profit out of ‘Adam Bede’, and gives it freely to Blackwood, which is a shame.”

When these rumours has started to circulate Lewes thought this might be useful in helping the real George Eliot maintain their anonymity, but as Joseph Liggins’ claims to be the author of ‘Scenes of Clerical Life’ and ‘Adam Bede’ spread and began to gain credibility, what at first seemed a funny turn of events became a stressful situation.

Evans was irritated and worried that Liggins was receiving charity on false pretences. A few days later she responded to a letter in the ‘The Times’ supporting the theory that Liggins was Eliot. She admitted that George Eliot was a pseudonym, but did not reveal that she was Eliot, and criticised attempts to expose the anonymity which the real author wished to maintain. Blackwood was persuaded to also publish a denial that Liggins was Eliot in June 1859, but he advised Evans that the true identity of Eliot should not be revealed, at least not yet.

Both author and publisher were acutely aware of the consequences of the identity of the real George Eliot being uncovered. If the details of Evans’ home life (she was living with Lewes who was separated from his wife, but could not get a divorce) were known it would damage her career prospects.

As a financially astute woman Evans knew how charges of immorality would affect her value in the literary marketplace, and yet she was unashamed of her relationship with Lewes, wishing to be called ‘Marian Evans Lewes’ by her friends and family. She was suspicious that her publisher might abandon her to protect his own interests. By the summer of 1859 a manuscript of Eliot’s work on the handwriting of Liggins was said to be circulating, but Evans was also becoming aware that it literary circles she was known to be the author behind the pen name George Eliot. It was even suggested that the Liggins affair was a cynical marketing ploy. Although Blackwood agreed that the pseudonym could be dropped, ‘The Mill on The Floss’ and all her subsequent novels were published as by George Eliot.

Although she lost the benefits of anonymity, George Eliot became a celebrated novelist.

The library’s exhibition ‘Pen Names’ explores a range of writers working in Britain from 1800 to the present day who published under pen names. It runs from 8 July 2022 to 29 April 2023. For more information see our website here. For more blog posts about authors who use aliases search #PenNamesNLS.

Links/Further reading:

Adam Abraham, ‘Being George Eliot: Imitation, Imposture & Identity’ in Plagiarizing the Victorian Novel, 2019 (shelfmark: PB8.221.154/7)

George Eliot Fellowship Reclaim the Name – George Eliot Fellowship

Guardian, ‘George Eliot’ joins 24 female authors making debuts under their real names https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/aug/12/george-eliot-joins-24-female-authors-making-debuts-under-their-real-names

Guardian, ‘Sloppy’: Baileys under fire over Reclaim Her Name books for Women’s prize https://www.theguardian.com/books/2020/aug/15/baileys-reclaim-her-name-wrong-black-abolitionist-frances-rollin-whipper-martin-r-delany

Kathryn Hughes, George Eliot: The Last Victorian, 1999 (shelfmark: HP1.200.7215)