This is a blog about four men, footballer Gil Heron (1922-2008), his son the musician Gil Scott-Heron (1949-2011), publisher Jamie Byng (1969-) and TV executive and football pundit Stuart Cosgrove (1952-). These men’s lives and the points where they crossed over tells us something about Scotland and its relationship with African-American culture over the last 70 years.

In an interview with the “The Daily Record” shortly after his father’s death in 2008, Gil Scott-Heron said “Like, that’s two things that Scottish folks love the most – music and football – and they got one representative from each of those from my family”.

The football representative was his father Gil Heron, the first black player for Celtic. Heron joined Celtic from Detroit Corinthians in August 1951. He made an immediate impact, scoring a goal in his debut match for Celtic, a 2-0 victory over Morton on 18th August 1951. Heron was known for his speed of play earning him the nicknames the Black Arrow and the Black Flash. The sharply dressed Heron also made an impact off the field, walking around Glasgow in yellow shoes, a trilby hat and a zoot suit. Heron though struggled to maintain a place in Celtic’s first team. John McPhail was already established in his preferred position of centre forward and he found it difficult to adapt to the very physical and aggressive style of play that was the norm in 1950s Scotland.

Heron would only make five first team appearances for Celtic and was released in 1952, joining another Glasgow club Third Lanark for whom he played seven matches and scored five goals. He then moved to England, playing in 1953-1954 for Kidderminster Harriers. Heron then moved back to America, re-joining Detroit Corinthians. During his stay in Scotland he made headlines on both sides of the Atlantic. His time in Glasgow also had a lasting personal legacy. He met Margaret Frize who would later join him in Detroit, where they married and had three children.

Heron was born in Jamaica and played for the Jamaican national football team. He shared the affection many Jamaicans have for cricket and during his time in Scotland played for Poloc Cricket Club in Glasgow and later for Ferguslie Cricket Club in Paisley, showing respectable form, on one occasion scoring a half century. His time in Scotland may have been relatively short but it had a big impact both on Scottish football and wider society. The Black Arrow was a trailblazer for black footballers in Scotland and the wider UK. His arrival in Scotland a few years after what is now known as the Windrush Generation of Caribbean immigrants began to come to the UK in 1948 helped pave the way for a future more multicultural Scotland.

The music representative from the Heron family was of course Gil Scott-Heron himself. He was born In Chicago, Illinois on 1st April 1949 to Gil Heron and Bobbie Scott, a librarian and opera singer. His father’s move to Glasgow broke up the family. Gil Scott-Heron was brought up in Tennessee by his grandmother Lily Scott, a musician and civil rights activist. Lily bought her grandson his first piano and introduced him to the work of Langston Hughes, whose poetry that drew on the rhythms of jazz music was a major influence on Scott-Heron.

Gil-Scott-Heron would not see his father for 26 years. One of Gil Heron’s daughters from his second marriage approached Scott-Heron after a concert and took him home to meet their father. A relationship developed, that while never close was based on mutual respect for the other’s achievements. By this time Scott-Heron was already a leading figure in popular music. His albums “Pieces of a man” (1971) and “Winter in America” (1974) brought together lyrics about social and political issues of the day with music that drew from soul, jazz and blues. His songs “The revolution will not be televised”, “Johannesburg” and “The bottle” are now regarded as classics. His 1970 spoken word poem “Whitey’s on the moon” questions whether the government should be spending vast sums on the Apollo missions whilst black Americans are marginalised.

“A rat done bit my sister Nell.

(with whitey on the moon)

Her face and arms began to swell.

(and whitey’s on the moon)”

It was widely played during the 50th anniversary of the moon landings in 2019 and featured heavily in the film “First Man” (2018) about Neil Armstrong. Scott-Heron’s musical achievements led to him being called both the Godfather of rap and the black Bob Dylan.

Fans began to wear Celtic tops at Gil Scott-Heron’s concerts in Glasgow, leading him to joke “There you go again – once again overshadowed by a parent”. On a promotional visit to Glasgow he said “My father still keeps up with what Celtic are doing. You Scottish folk always mention that my dad played for Celtic. It’s a blessing from the spirits.”

Jamie Byng is the scion of a wealthy and titled family. Schooled at Winchester College, he then attended the University of Edinburgh. In Edinburgh he set up a club night “Chocolate City” named after a song by the funk group Parliament led by George Clinton. The song expresses Clinton’s pride in North American cities that have a majority black population. It imagines what America would be like with a black president. In the song Muhammed Ali is President, James Brown is Vice President, Stevie Wonder is Secretary of Fine Arts and Aretha Franklin is First Lady.

After graduating Byng stayed in Edinburgh and got a job with Scottish publisher Canongate. Established in 1973 Canongate setup the Canongate Classics imprint, which brought back into print many long unavailable Scottish literary classics. It both expanded and made much more easily available the Scottish literary canon. In 1981 Canongate added to the Scottish literary canon themselves, when they published Alasdair Gray’s first novel “Lanark”.

The financial situation of Canongate though was rocky. Byng led a management buyout of the company from its founders Stephanie Wolfe Murray and Angus Wolfe Murray in 1994. Byng began to publish more non-Scottish books, aiming to secure the publishers future by making it a national and international success.

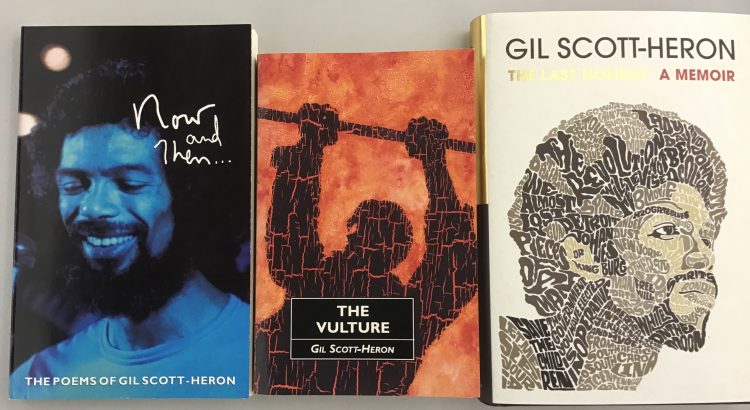

Byng’s interest in black American music and the African-American culture it emerged from led him to set up a new imprint “Payback Press”. Named after a classic 1973 album by James Brown “The Payback”, the imprint published non-fiction works on black music and culture, many of which might have otherwise struggled to get a UK publisher. At the core of its output though were reprints of classics of African-American literature by amongst others Chester Himes, Clarence L. Cooper, John Edgar Wideman, Iceberg Slim and Gil Scott-Heron, who as well as being a musician was a novelist and poet. Canongate made these books more attractive for a contemporary audience by commissioning new introductions by figures like rapper Ice T and novelist Irvine Welsh. The works of a generation of black American authors, many out of print and in danger of falling into obscurity in their native land, were finding a new audience thanks to an Edinburgh publisher.

Amongst the books republished by Canongate was Scott-Heron’s 1970 novel “The Vulture”. Byng was not just his publisher. The two men would also develop a close friendship. Scott-Heron would become a godparent to Byng’s daughter Marley and son Leo. Canongate would posthumously publish Gil Scott-Heron’s autobiography “The last holiday” in 2012. This and his other books are still in print from Canongate. A video of Gil-Scott-Heron in conversation with Jamie Byng is available on the Canongate website.

https://canongate.co.uk/wall/gil-scott-heron-interviewed-by-jamie-byng

Canongate’s commitment to publishing African-American writers was further demonstrated when they signed a contract with a then obscure American senator to publish his 1995 memoir “Dreams from my father” and his 2006 book about politics “The audacity of hope”. The books would become bestsellers for Canongate and their author Barack Obama would be elected President of the United States.

Stuart Cosgrove is the outlier in this group. His hilarious book “Hampden Babylon” about sex and scandal in Scottish football was published by Canongate in 1991 and he is a fan of Gil Scott-Heron’s music. He included Scott-Heron’s “The revolution will not be televised” in an article listing soul records to play on election day published in The National newspaper on 8th December 2019. Otherwise, he has no strong connections to the other three. He does though show that in Scotland a passion for football often goes together with a passion for music.

Stuart Cosgrove was born in Perth and growing up would develop two great obsessions. He is a lifelong supporter of Perth football club St Johnstone, he could see their ground from his childhood home on Perth’s Tulloch estate. Cosgrove was also a self-described “young Scots soul rebel”, dancing to and collecting obscure American soul records, writing soul fanzines and early in his media career joining the staff of the British black music magazine “Echoes”. Best known today as a football pundit on BBC Scotland’s “Off the Ball” and “Sportscene”, he gave up a possible academic career to become a journalist at “NME” and “The Face” and then was a television executive at Channel 4 from 1994 until 2015. Since leaving Channel 4 he has made a career of writing and broadcasting on his two childhood obsessions, Scottish football and soul music.

Cosgrove is the author of the Soul trilogy, “Detroit 67: the year that changed soul” (2015); “Memphis 68: the tragedy of southern soul” (2017) and “Harlem 69: the future of soul” (2018). Cosgrove visited libraries in Detroit and other parts of America to write his deeply researched books. They use a chronological, month by month format to tell the stories of record label owners, musicians, singers and club owners, set against a background of race riots; the Vietnam War; the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr and the emergence of the Black Panther Party. The final book in the trilogy tells the stories of Nina Simone, James Brown, Donny Hathaway, Jimi Hendrix and a young aspiring poet and musician called Gil Scott-Heron. Across the trilogy we see soul music change and develop from a singles based genre to a vehicle for album length song cycles and its subject matter widen to include direct political and social statements. The books shows how a genre mainly known in the mid-1960s for dance records and love songs had by the 1970s become a home for albums such as Marvin Gaye’s “What’s going on” (1971), Sly and the Family Stone’s “There’s a riot goin’ on” (1971) and Gil Scott-Heron’s “Pieces of a man” (1971), albums which are both personal and political statements.

Whilst writing this blog I came across another Scottish connection with both Gil Heron and Gil Scott-Heron. Gerry Hassan (1964-) is a Scottish academic and commentator who became a fan of Gil Scott-Heron after seeing him at the Dundee Jazz Festival in the 1980s. It is likely that another attendee at that concert was Dundee born singer and songwriter Michael Marra (1952-2012). In April 2008 Hassan visited Scott-Heron’s home in Harlem, New York to give him a recording of a song by Michael Marra “Flight of the Heron” about Gil Heron’s time at Celtic. Hassan wrote about the visit in an article for the Sunday Times on 7th December 2008 which is available on his blog

When he saw Scott-Heron perform in Dundee, Hassan did not know that his father had played for Celtic. Based on this information Hassan makes the somewhat audacious statement “that we could claim Gil Scott-Heron and the whole genre of socially engaged hip hop and rap as ‘Scottish’”. Hassan and Scott-Heron listen to Marra’s song about Gil Heron, which Hassan says leaves them both close to tears. After the visit Hassan reflects on Gil Scott-Heron and Michael Marra, two very different men but brought together by football and music, concluding that “both in their way are Scottish spirits”.

You can listen to Marra’s song on YouTube

The chorus of Marra’s song perhaps gets to the essence of the story of Gil Heron, Gil Scott-Heron and Scotland.

“Higher, raise the bar higher

He made his way across the sea

So all men could brothers be”