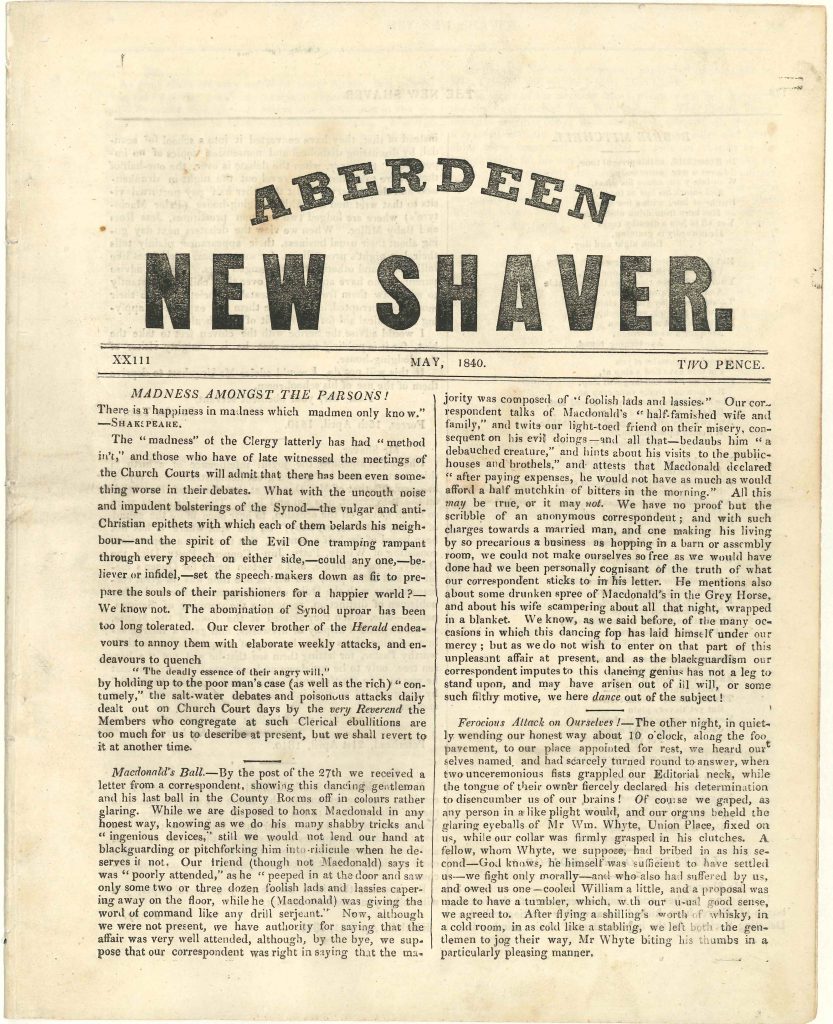

We have recently published images of some early Scottish newspapers on our Digital Gallery, ‘Scotland’s News’, including the short-lived scandal sheet the Aberdeen new shaver

The 1830s in Scotland, like the rest of Great Britain, was marked by bitter political divisions between Tories and Whigs, and by radicals fighting for the reform of the political system. The city of Aberdeen was also marked by the ideological fervour that had gripped the nation. The 1830s was the most prolific decade of the 19th century for new titles appearing in the city. Amidst all the earnest debate in print, a few mischievous Aberdeen printer/publishers entered the fray to produce some cheap satirical publications, which took malicious pleasure in exposing the failings of leading local figures. The Aberdeen new shaver, edited, printed, and published by Robert and William Edward from 1838 onwards, was one of a line of publications starting in 1832 with the Aberdeen pirate, followed by the Aberdeen mirror in 1833 and Aberdeen shaver of 1837.

The content of the Aberdeen new shaver was a mixture of gossip, local news and comment, and letters to the editor. It is likely that most, if not all, of the content of the Aberdeen new shaver was in fact written and sometimes invented by the Edwards. They, like their predecessors and rivals, ran the risk of being sued for libel, so they either avoided naming people directly or had to refer to their misdemeanours in an oblique manner, but sometimes they could be just plain rude. In June 1840 they revealed under the heading ‘The shaver in trouble,’ “We have been often threatened with extermination, but we have weathered out in defiance of all the plots which have been laid to o’er-master us. How long we may be so lucky we know not.” They also had to avoid being pursued by the Stamp Office for not charging stamp duty, the tax imposed on newspapers. By publishing on a monthly basis, they ensured that were not classed as a newspaper, which meant their title lacked some topicality, but cost half the price of local newspapers. They also, on occasion, published a ‘supplement’ to get out an additional issue during a calendar month.

As the title of the periodical suggests, the goal of the Aberdeen new shaver was to administer “razor cuts” in print to people in the public eye. A sample of these “cuts’” is as follows: “A fat-bellied clerk named Craig at the London Steam Company’s office, should give over his visits to the girl Cattanach in Prince Regent Street”; “in the service of Mitchell of Thainston there is a highland booby of a butler, who is a talebearing, unmannerly fellow, and who is hated amongst his fellow-servants for communicating tittle-tattles about the house to the master”. Even Queen Victoria is not spared some acid comments. In number 20 for February 1840, it is noted that she is about to be married to a ”poor German” and that she wanted “one hundred thousand [pounds annual allowance] for this watery faced thing of a German”, such extravagance was bound to be unpopular “when so much discontent and distress prevails in the country”.

The Aberdeen journalist John Malcolm Bulloch, commenting nearly 50 years after the 25th and final issue of the Aberdeen new shaver in July 1840, noted that it was “badly printed, and miserably edited … a far less able production than the paper [the Aberdeen shaver] from which it took its name.” No doubt the Edwards would have shrugged off this criticism and pointed out that a tuppence scandal rag was never meant to be high-quality journalism. The ephemeral nature of these publications means that very few copies of them survive today. The Library run of the Aberdeen new shaver is missing a few issues; however, enough survives to give us a good idea of Aberdeen gossip of the period.

You can find out more about our work to conserve early Scottish newspapers here.

If you would like to donate to our appeal to enable us to continue working on newspapers at risk, you can find out more here.