David Lyndsay was the pseudonym of the author born Mary Diana Dods, and who from 1827 lived as Walter Sholto Douglas.

Details about their life are patchy. It was the researcher Betty T. Bennett, editor of Mary Shelley’s letters who first made the connection between Dods, Lyndsay and Douglas in the 1980s. Bennett’s research at the National Library of Scotland and National Records of Scotland established that Mary Diana Dods was born around 1790, the illegitimate daughter of a Scottish aristocrat (George Douglas, Earl of Morton) who grew up in London and Dalmahoy House, Ratho, and died as Walter Sholto Douglas in a debtor’s prison in Paris around 1830.

At the time that Dods used the pen name David Lyndsay they were living as a woman in London, their only regular income an allowance from their father. Literary work was a useful way for women to make money in the nineteenth century, and it was not unusual for women to publish anonymously or pseudonymously in this period. Although it became less common for novels to be published anonymously after 1800, the practice persisted in literary magazines. Many contributions to journals were unsigned, or gave only the author’s initials or forename.

In the 1820s Dods contributed to periodicals including ‘The Literary Pocket Book’, ‘The Literary Souvenir’ and ‘Blackwood’s Magazine’ – some of their works were attributed to David Lyndsay while others were anonymous. It was as Lyndsay that a collection of their poems and stories, which originally appeared in ‘Blackwood’s Magazine’, was published in Edinburgh as ‘Dramas of the Ancient World’ in 1822. These stories explored classical and biblical themes, some of which were also featured in the work of the contemporary poet Lord Byron. Lyndsay felt that the critics might feel this arrogant for a young writer:

“Lord Byron’s majestic drama I have read with feelings of mingled wonder admiration and regret – What a noble performance it is and how delightfully the Edinburgh Reviewers will cut up little David into mince meat for his presumptuous seating himself so quietly side by side with this Goliath of Tragedy.”

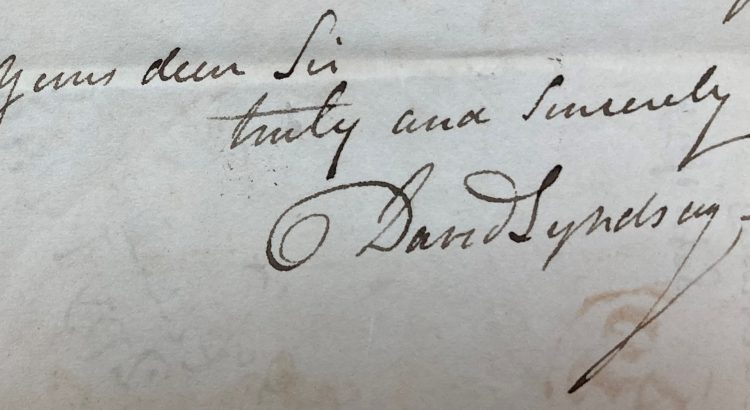

Lyndsay was not only used as a pseudonym in print it was also the name used in correspondence with their publisher. William Blackwood (1776-1834) was the founder of the publishing house William Blackwood & Sons, based in 17 Princess Street (and later 45 George Street), Edinburgh. As the publisher of authors such as James Hogg and Sir Walter Scott Blackwoods was a notable and popular publishing house. In order to conceal their identity Lyndsay used a go-between to receive letters. Blackwood suspected that Lyndsay was a pseudonym (sometimes Lyndsay was misspelled). He told Lyndsay:

“I have been so much accustomed with my Magazine correspondents assuming names, that when I hear from a stranger I am always uncertain whether or not I see a real or an assumed signature. I never however ask farther than what my correspondents choose to communicate.”

But Blackwood was curious and in early 1822 he wrote to a London publisher Charles Ollier looking for information about Lyndsay’s real identity. Later that year David Lyndsay revealed to Blackwood that this was not their real name:

“I hope my dear Sir, and kind countryman, that you have not felt offended by the incognito which I am for strong reasons obliged to keep. I am at present bound by a promise, which for a time compels me not to acknowledge my authorship. That restraint will not last forever though I may not put my name to my vols, it shall be no secret to you, and I flatter myself you will not be ashamed of having call’d me forward to a literary existence – this is entirely entre nous –”

Unfortunately the ‘Dramas’ was not a success. Although Dods continued to write, and had encouragement from literary friends like Mary Shelley, Blackwood did not accept any further work from David Lyndsay – although he did print two pieces in 1826 sent by someone signing themselves Isabel Douglas, wife of Sholto Douglas. One of these stories ‘Transmogrifications’ describes a boy growing into a man in a series of sketches.

The following year, in 1827, Dods decided to move to Paris and become Walter Sholto Douglas, husband of Isabella Robinson, and father to Robinson’s illegitimate child. Now they took on a new identity both on and off the page. It has been suggested that living as a man opened up employment opportunities and that the arrangement with Isabella Robinson was mutually convenient. But it is also possible that Dods identified as a man, and/or was in a relationship with Robinson. Bennett’s book was written in a period when LGBT+ history was not well understood, some historians today have been more confident in suggesting that had they lived today Dods/Douglas might have identified as trans.

We will never know for sure how they understood their gender identity, but their life offers an insight into how some pen names may be more than a convenient literary convention, but hold a deeper significance.

References/further reading

Betty T. Bennett, Mary Diana Dods, A Gentleman and a Scholar: The Astonishing Revelation of a Daring 170-year-old Deception, 1991 (Shelfmark: H3.92.2434 and HP2.95.2000)

Geraldine Friedman, ‘Pseudonymity, Passing, and Queer Biography: The Case of Mary Diana Dods‘

Natasha Tidd, The Mystery of Walter Sholto Douglas

William Blackwood and Sons Archive

Jennie Batchelor, ‘Anon, Psed and “By a Lady”: The Spectre of Anonymity in Women’s Literary History’ in Batchelor and Dow Women’s Writing, 1660-1830: Feminisms and Futures, 2016 (Shelfmark: HB2.218.2.101)

David Lyndsay, Dramas of the Ancient World

The library’s exhibition Pen Names explores a range of writers working in Britain from the 1800s to the present day who use pen names. The exhibition runs from 8 July 2022 to 29 April 2023. For more information see www.nls.uk/exhibitions/pen-names/ For more blog posts about authors who use aliases search #PenNamesNLS.