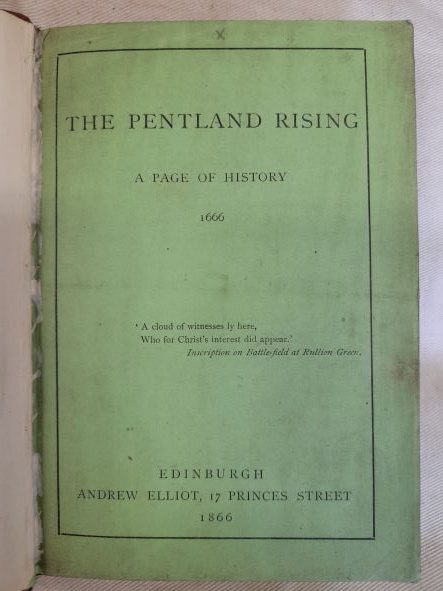

At the age of fifteen Robert Louis Stevenson penned “The Pentland Rising: A page of history”. This is a vivid and eloquent recreation of the events that led to the Covenanters’ military engagement with Royalist forces on 28 November 1666. This event, the Battle of Rullion Green, took place exactly 355 years ago today. Stevenson’s deep interest in the Covenanters had already found expression in a romance he had started to write. Louis’s father Thomas steered him away from this literary genre towards writing a historical account. His incentive was the offer to pay for its publication. The booklet would appear on the 200th anniversary of the battle, on 28 November 1866. Louis’ efforts resulted in a serious scholarly narrative of the Pentland Rising, complete with footnotes and historical references.

Andrew Elliot printed 100 copies of the little 22-page volume but Thomas Stevenson, fearing criticism, bought just about every copy himself. Not even family members or friends got one. The Library owns one of the very rare copies that still exist.

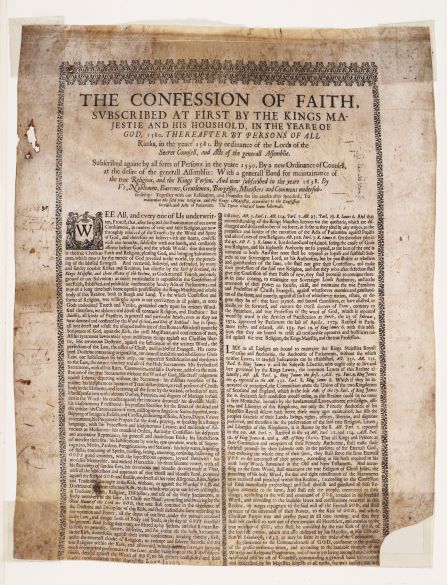

The Covenanters were 17th-century Scottish Presbyterians who resisted the introduction of Episcopalianism in Scotland. In 1638 they drew up an agreement opposing the Government’s church reforms, the National Covenant. The text of the Covenant was copied both by hand and on printing presses and numerous copies of it were sent round Scotland for its supporters to sign.

After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Presbyterian ministers were forced to renounce the Covenant or be expelled from their positions. More than 250, or about a third of all ministers, left their charges and started preaching in secluded, secret spots in the open air. Large numbers of their parishioners chose to attend these conventicles rather than a church service conducted by an Episcopalian curate.

In Stevenson’s hands, the story unfolds from here with a stirring account of the events that eventually led to the Covenanters’ uprising. Based on historical resources, he describes how roll calls were introduced at Sunday church services and heavy fines imposed on the absentee parishioners. Before long, they were ruined, then their possessions were confiscated and finally their houses burnt down.

What follows is a day-to-day account starting in Dalry in southwest Scotland on 13 November 1666, when four Royalists, intent on roasting an old man alive as punishment, were stopped by four “countrymen”, who shot their leader, Corporal Deanes. Deanes was taken to Dumfries, where he claimed to have been shot because he refused to sign the Covenant.

With great skill and verve, Stevenson relates how the Covenanters assembled in Dumfries, from where they marched via Douglas, Lanark and Bathgate towards Edinburgh. Armed peasants joined them on the way, but during the exhausting march through the cold, wet and windy countryside, many fell away again.

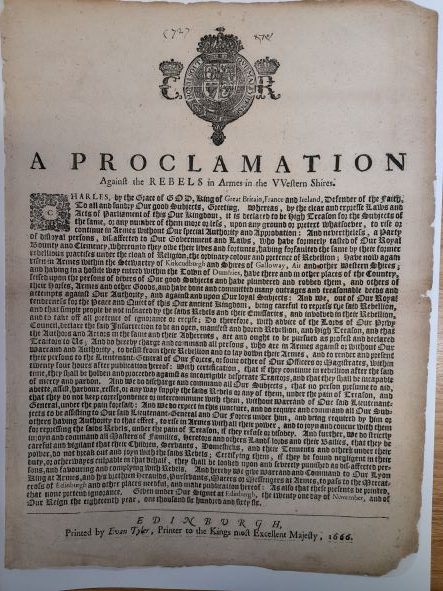

On 21 November, King Charles II issued a proclamation that declared those who rebel with weapons against his government are to be considered traitors.

On 28 November at sunset the much reduced Covenanter forces reached Rullion Green in the Pentland Hills some eight miles south of Edinburgh, where they were engaged by Royalist troops. Stevenson describes the military action and positions, how the Royalists were at first repulsed but then overcame the outnumbered Covenanters. His account of the aftermath is nothing short of passionate: having killed about 50 Covenanters and taken the rest prisoner, the Royalists marched to Edinburgh where the prisoners were executed for treason. Some had managed to flee but were persecuted and, when captured, plundered and murdered.

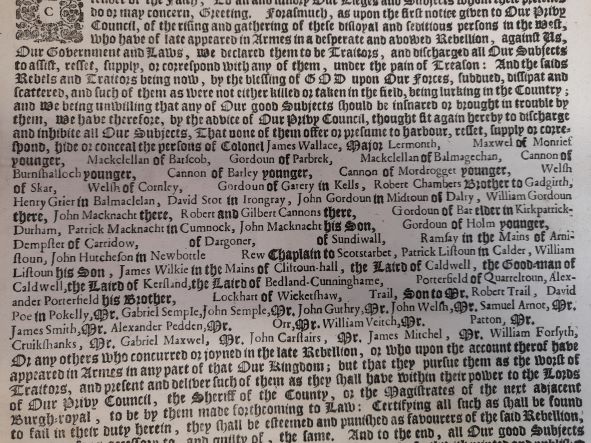

On 4 December another royal proclamation was issued, which declared the fugitive Covenanters outlaws, meaning that nobody was to rescue or even shelter them. The names of the most wanted men were inserted into the text of the proclamation.

One Rullion Green fugitive, John Carphin from Ayrshire, was badly wounded in the battle but managed to escape. He started on his was back home across the Pentlands towards Ayrshire when he came across the house of Adam Sanderson of Blackhill, a local shepherd. Not wanting to implicate the shepherd, he refused his help and died on the hills. Sanderson then carried the body to a spot from where the hills of Ayrshire are visible. A gravestone erected in the 19th century marks that spot.

You can read Stevenson’s highly engaging first publication, the “The Pentland Rising”, online in our Digital Gallery.