From the middle of the nineteenth century, Norway became a popular destination for aristocratic British fishermen. They became known there as “salmon lords”. John Francis Campbell (1821-1885) was one of them but he did more than live a life of leisure. He was a noted linguist and folklorist, collecting Gaelic folktales, songs, anecdotes and more.

Now regarded as a key figure in early Celtic studies, Campbell had a close relationship to his home island of Islay. Campbell also travelled widely beyond Scotland and developed an interest in natural sciences, particularly geology and climatology.

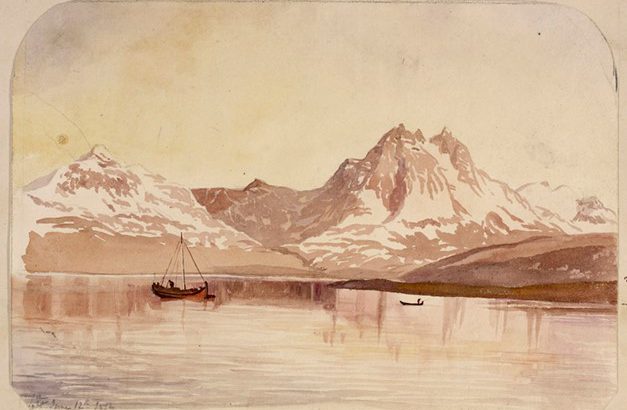

Campbell’s journals from his travels, held in the collections of the National Library of Scotland, are fascinating objects in their own right. They are multimedia texts, containing sketches, watercolours, photographs, receipts, business cards and rubbings of different rocks, as well as Campbell’s handwritten accounts of his travels. One journal from Scandinavia even contains a piece of whale skin! The sketches and watercolours are Campbell’s own, but he often bought the photographs when travelling and added them to the journals at a later date.

As part of my placement at the Library, I have been investigating what Arctic materials the Library’s collections contain, especially the Mountaineering and Polar Collections. Campbell’s travel to Scandinavia fits neatly with all three of my main strands of research: Scottish involvement with the Arctic, tracing climate change in the collections and looking for Indigenous voices in the collections.

Campbell’s northern journeys were mostly made through Sápmi, the homeland of the Sámi people, which covers northern Norway, Sweden and Finland and the area around the Kola peninsula in Russia. He made fishing trips to the Tana and Alta rivers in 1849, 1851 and 1852, keeping journals and painting watercolours. He also made a trip to Sápmi in 1873, as part of a long tour through Europe and the Russian empire to research geological change.

Campbell’s scientific work is valuable and could be seen as part of the beginnings of climate science. Other Scots like James David Forbes also took an interest in how the glaciers of Norway changed over time, something that climate change has only accelerated today. Campbell’s travels reveal another side to Sápmi and the Arctic more generally. Far from being a pristine and empty space, places like Kåfjord/Njoammelgohppi near Alta/Áltá were well-known for their mines and industry. As in Scotland, whaling was a significant business and the scrap of whale skin which Campbell placed inside his 1873 journal is a fascinating trace of this.

Campbell was also a linguist and learnt Scandinavian languages, including Northern Sámi. One particularly interesting piece of ephemera inserted into his journal is one of the first editions of Muitalægje, the first newspaper printed in a Sámi language. Printed in Vadsø/Čáhcesuolu in 1873, Campbell must have collected it on his journey. It is interesting to consider it as an example of how Arctic Indigenous voices can be found in the Library’s collections, tucked away – quite literally – in the journals of a Scottish traveller.

Campbell’s relationship to the Sámi was complex. For all his interest in their language and culture, this often took the form of collecting ethnographic information. Campbell measured the heights of many of the Sámi he met and contributed an article to the Ethnological Society of London’s journal. He also met Jens Andreas Friis, a linguist at the University of Kristiania (now Oslo), who made ethnographic maps of Sápmi. Despite Friis’ and Campbell’s interest in preserving Sámi culture and languages, it is hard to disentangle their projects from the Norwegianization programmes of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These sought to destroy Sámi culture and languages and attempted to assimilate the Sámi into Norwegian society.

We do, however, come across Sámi voices in Campbell’s work. His scientific research often drew on local knowledge of the places he travelled through, including in Sápmi. We can also see Sámi involvement in Campbell’s artwork. A striking portrait of Mathis Isaksen, the postmaster at Karasjok/Kárášjohka, is one of the highlights of Campbell’s journals. Notably, Isaksen took the time to sign the portrait himself. It is an interesting example of how the Sámi interacted with Campbell beyond simply being passively depicted by him and another example of Indigenous presence in the Library’s collections.

Christian Drury, Placement student, Mountaineering & Polar Collections