The Scottish author Nancy Brysson Morrison (1903-1986) is chiefly remembered today for her novel ‘The Gowk Storm’ a story about three daughters of a Scottish church minister. First published in 1933, the book was reissued as part of the Canongate Classics series in 1988. Morrison’s first two books were published by John Murray and the ‘The Gowk Storm’, published by Collins, was her third novel.

Nancy’s novels were issued under the name N. Brysson Morrison. It was probably to avoid confusion with another contemporary author called Nancy Morrison, although Lord Gorell at John Murray advised that she should not worry about this since “it is yours and not a name taken for the purpose [of publication]”.

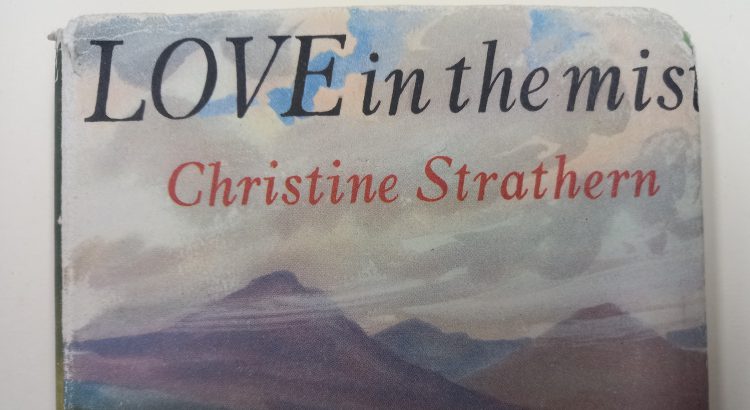

Morrison was dropped by Collins (as she had been by Murray) after two novels, however, during the 1940s and 50s she continued to write for Collins. As Christine Strathern she published mainstream romantic fiction. This included 27 novel-length books for Collins and short stories to D.C. Thomson’s ‘The People’s Friend’. Morrison’s more commercial work provided income which allowed her to continue to write literary fiction. At her death in 1986 Morrison had published 11 novels and a number of biographies and other non-fiction titles under her own name. Some of her Strathern novels were still in print in the 1970s and 80s by which time many of the books she published as Morrison were unavailable.

Morrison’s papers, which include manuscripts, letters and notebooks, were acquired by the National Library of Scotland towards the end of her life, and after her death. However, it is an incomplete picture of her writing life as it does not chronicle her career as Christine Strathern. Only one mention of a Strathern title, in a letter from her sister Peggy, has been found in her papers.

Five of the six Morrison siblings were writers. Nancy’s brother Tom, published as T.J. Morrison and her sister Peggy used the pseudonym March Cost. Nancy’s pen name is that of a character from ‘The Gowk Storm’, which, it has been suggested by her biographer Mary Seenan, was perhaps chosen because of the character’ sentimentality. The Morrisons may have been influenced by the Brontë sisters in their use of pen names (Nancy published a biography of the sisters ‘Haworth Harvest’ in 1969).

It seems likely that only those very close to her knew of Morrison’s double life. If anyone guessed at Strathern’s identity it was not made public until after her death. Her literary executor suggested it would be wrong to see Morrison as “a writer of romances”, and that she “would not like that at all”.

The plots of her Strathern novels, however, meet the expectations of the romance genre, and include happy endings. It is interesting, however, that in both her Morrison and Strathern books she drew on her Scottish heritage, often featuring Highland and Lowland locations including Glasgow. Perhaps influenced by the success of Annie S. Swan (1859-1943), it seems to have been a selling point of the books. The blurb for ‘Love in the Mist’ (1955) claims: “Christine Strathern imbues this romantic story with all her own abiding love for her native Scotland”.

As Morrison never spoke publicly about her pseudonymous work we do not know her feelings about it. In the lectures she gave about writing in the 1950s she joked about her sister’s alter-ego March Cost receiving letters from an admiring female fan, and men who claimed to have played golf with Cost. However, the text of these talks also show that she understood pen names as a way for women to mitigate gender-bias.

“women were treated like children in that they were expected to be seen in their proper place, the home, but not heard out of it, certainly not to do anything so improper as write a book. Marion Evans hid her sex under the name of George Eliot, matrons retained their husband’s designation as the insignia of respectability, Mrs. Gaskell, Mrs. Oliphant, Mrs. Henry Wood, Mrs. Humphrey Ward, and each of the three Brontës assumed a masculine nom-de-plume.”

In her lectures Morrison expressed admiration for the business-sense of women novelists of the nineteenth century, however, it is probable that she felt that if she were known to be the author of light romantic novels, Christine Strathern, this would damage her standing in the literary world. Nancy Brysson Morrison’s story highlights the compromise between commercial realities and literary aspirations which many authors had, and continue, to face.

The library’s exhibition Pen Names explores a range of writers working in Britain from the 1800s to the present day who use pen names. The exhibition runs from 8 July 2022 to 29 April 2023. For more information see www.nls.uk/exhibitions/pen-names/ For more blog posts about authors who use aliases search #PenNamesNLS.

Links/Further reading:

Alison Lumsden, ‘Morrison, Agnes Brysson Inglis [Nancy]’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (available through e-resources)

Mary Seenan, Nancy Brysson Morrison: A Literary Life, 2013 (shelfmark: PB8.213.394/11)

Papers of Nancy Brysson Morrison (shelfmark: MSS.27287-27373)

John Murray Archive, book file for ‘Breakers’ (shelfmark: Acc.12927/243 CP28)