A year has passed since National Library of Scotland staff began remote working due to the COVID-19 crisis. The adaptability of the Library’s personnel to their new circumstances and the use of Microsoft Teams, Zoom video conferencing, and the accessing of files and databases through a VPN (virtual private network) has enabled the mission, work and outreach of the National Library to continue unabated.

One of the pleasures of working from home has been the opportunity to play recorded music while cataloguing, researching, answering email queries from readers, etc. A few weeks ago, I put on a CD of German composer Paul Hindemith’s (1895-1963) song cycle Das Marienleben opus 27. Based upon poems on the life of Mary by Rainier Maria Rilke (1875-1926), it is a masterpiece of the song-cycle genre. Pianist Glenn Gould (1932-1982) thought it the greatest work of its kind ever written. When the fifth song, “Argwohn Josephs”, started playing I was struck by its musical and stylistic similarities to the opening movement of the composer’s only recently discovered Klaviermusik mit Orchester nur linke Hand (Piano Concerto for the Left Hand) opus 29.

Listening to recordings of both pieces on YouTube reveals that we are in the same sound world:

Argwohn Josephs:

Klaviermusic mit Orchester nur linke Hand:

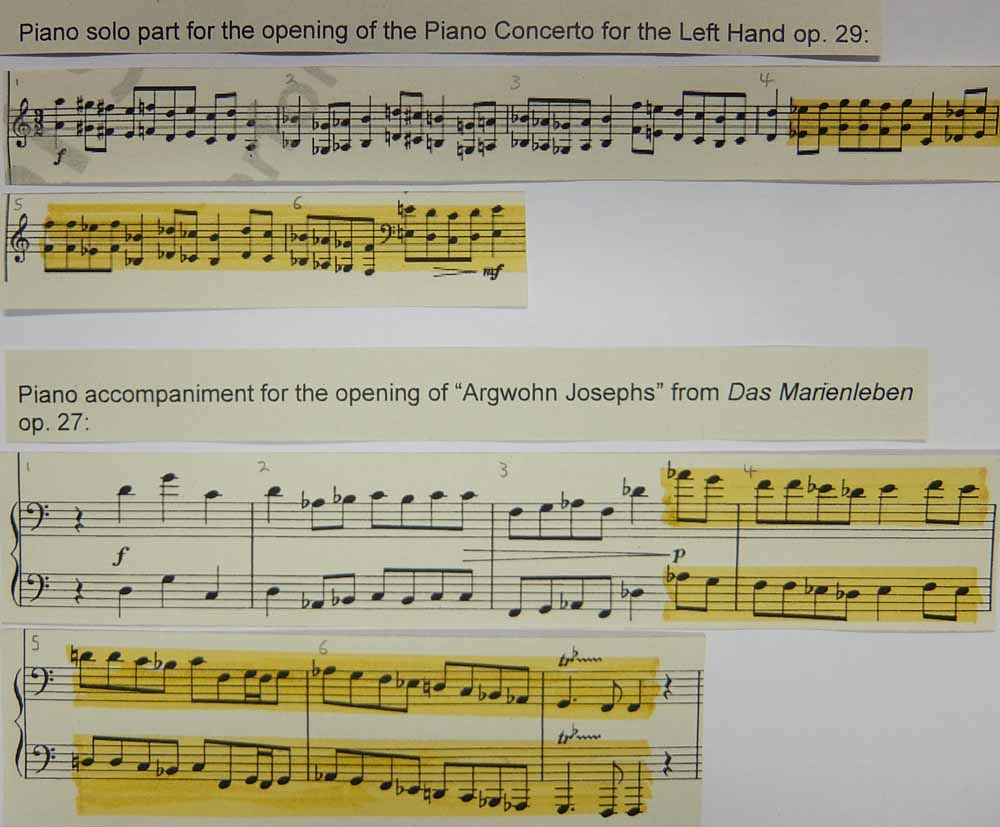

Things become clearer when looking at the printed scores for these works. Both the piano accompaniment in the song and the solo piano part in the piano concerto are characterized by the same driving musical rhythms and repeated melodic patterns, with harmonies outlined in stark parallel octaves. Their piano parts mirror each other in many places as can be seen below in the conclusion of their respective opening musical statements (outlined in yellow) in bars four to six of both works.

SCHOTT MUSIC GmbH & Co KG, Mainz.

Thematic connections for Hindemith’s Klaviermusic mit Orchester and Das Marienleben were likely given the circumstances of their composition. In June 1922, Hindemith had started writing Das Marienleben but in November of that year he interrupted work on it to accept a commission for the concerto which he finished composing in April 1923.

Now the story becomes intriguing. The request had come from Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961), a concert pianist who had lost his right arm in the First World War. He was the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951), and they were members of a wealthy family of Viennese industrialists. To continue his performing career after his injury, Paul Wittgenstein had commissioned left-hand piano works from leading composers of the 1920s for his exclusive use. Possibly the most famous, and the only one regularly programmed in concerts today, is Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand in D major.

Wittgenstein paid Hindemith a commission of $1000 US dollars. To receive such a large amount in hard currency during the Weimar Republic’s hyperinflation crisis in the early 1920s (the equivalent at the time of 30 million Marks!) put Hindemith in an extremely good financial position. He used the money to acquire and renovate the 14th century Kuhhirtenturm (Cowherds’ Tower) in the centre of Frankfurt and make it his family home. Although severely damaged in World War II, it was reconstructed in 1957 and now houses exhibition and lecture space of the Hindemith Foundation.

Unfortunately, the fate of the concerto was not a happy one as Wittgenstein never performed it and reserved exclusive rights to its use. Even when he died in 1961 his widow refused access to the score. It was only after her death in 2001 that an executor made the score available to the Hindemith Foundation.

However, there was a further mystery as upon examination the score was found not to be the composer’s autograph manuscript, but a copy in a different hand. A comparison with Hindemith’s extant short-score sketches confirmed that it was the best available source for the work. A performing version was published in 2004 and the concerto, following this version, finally received its world premiere in December 2004 with the Berlin Philharmonic and the American pianist Leon Fleisher (1928-2020) as the soloist. Fleisher had lost control of his right hand in his thirties due to a neurological disorder and played many of the works Wittgenstein had commissioned.

Good news arose from the publicity of the premiere as the original autograph score which Wittgenstein had received was eventually found in the manuscript collection of Arthur Wilhelm (1899–1962), an economist from Basel. Interestingly, Wittgenstein’s pencil fingerings in the original autograph proved that he had not rejected the work immediately, but only after having studied the music. These materials were later transferred to the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, making them available to the public.

Further reading:

Das Marien-Leben. Gedichte von Rainer Maria Rilke. Für Sopran und Klavier. Neue Fassung (1948) der Original-Ausgabe opus 27 (1922-1923) (Mainz: B. Schott’s Söhne, c1948)

Shelfmark: Mus.Box.287.26

Selected Letters of Paul Hindemith; Edited and Translated from the German by Geoffrey Skelton. (New Haven ; London: Yale University Press, c1995)

Shelfmark: H3.96.1587

Paul Hindemith: a guide to research. Stephen Luttmann. (New York, N.Y. ; London: Routledge, 2005)

Shelfmark: HB2.209.7.1351

Paul Hindemith: the Man Behind the Music, a Biography. Geoffrey Skelton. (London: Gollancz, 1975)

Shelfmark: H3.96.1587

The Music and Music Theory of Paul Hindemith . Simon Desbruslais. (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2018)

Shelfmark: HB2.219.5.149