The use of pseudonyms by the Brontë sisters is perhaps one of the best known examples of the use of pen names in English literature. This post focusses on Charlotte Brontë (1816-1855), whose novel ‘Jane Eyre’ was published 175 years ago in October 1847. It was Charlotte who persuaded her sisters to submit their writing for publication and was most active in protecting their reputations.

Emily and Anne Brontë insisted upon using pseudonyms. The siblings took the surname ‘Bell’ and chose forenames which started with the same letter as their own forenames (Charlotte = Currer, Emily = Ellis, Anne = Acton). Although all three sisters wrote novels individually, their first publication was a collection of poems to which they all contributed.

‘Poems’ by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell was published for the sisters at their own expense by Aylott & Jones in 1846. As C. Brontë, Charlotte had made the publication arrangements by letter, pretending to act as an intermediary for the authors.

Charlotte later explained:

“Adverse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women – without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called ‘feminine’ – we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice[.]”

The authors sent complimentary copies to literary journals and they received a few good reviews, but sales were poor – only two copies were bought. The unsold copies were later re-issued by Charlotte’s publisher Smith, Elder & Co after the success of ‘Jane Eyre’.

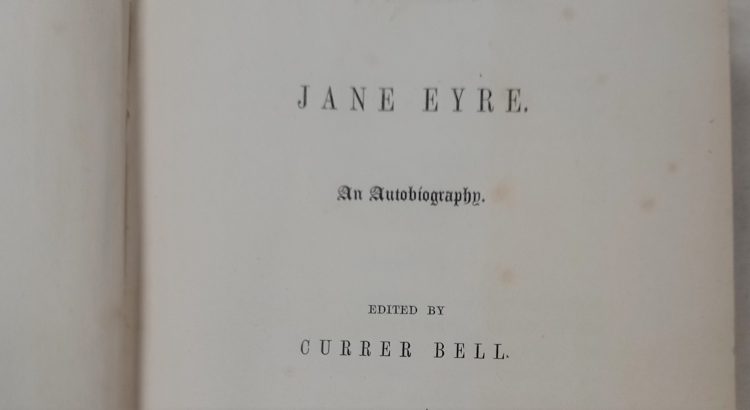

Charlotte’s most famous novel was published as ‘Jane Eyre. An autobiography’ edited by Currer Bell. Claiming to be the editor of Eyre’s story put some distance between Charlotte and her heroine’s story. But it did not prevent speculation about the authorship of the novel and particularly whether it was written by a woman.

John Gibson Lockhart was sent the novel as editor of the ‘Quarterly Review’ an influential periodical published by John Murray. He through it must be by a man or “a very coarse woman”. He considered it as good as established novelists of the period such as Anthony Trollope and Harriet Martineau, but thought the heroine “rather a brazen miss”. Lockhart commissioned Elizabeth Rigby (later Lady Eastlake) to review ‘Jane Eyre’. In her infamous 1848 review she claimed it was a dangerous book, with an unrepentant and rebellious heroine.

Suggestions that Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell were one person forced the sisters to act. In order to convince her publisher, George Murray Smith, that there were three Bell siblings Charlotte and Anne travelled to London in July 1848. George Murray Smith (1824-1901) was a partner in the publishing house Smith, Elder & Co founded by Scots George Smith and Alexander Elder in 1816. Charlotte and Anne confided to Smith and Charlotte’s editor William Smith Williams that they were Currer and Acton Bell (Emily refused to accompany them and did not want her identity to be revealed).

Biographer Juliet Barker has suggested that Charlotte wanted to move in literary circles and after her sisters’ deaths no longer felt bound to maintain the anonymity which prevented this. But although Charlotte revealed the identity of the Bell siblings in prefaces to new posthumous editions of ‘Wuthering Heights’ and ‘Agnes Grey’ (Emily died in 1848, Anne in 1849), she maintained the pen name Currer Bell until her final novel ‘Villette’ in 1853. In letters written to various correspondents around 1850 she looked back on the period before her identity as Currer Bell was known. She told Williams “I am ashamed of nothing I have written – not a line”, but she also reflected to Elizabeth Gaskell that anonymity had given her courage to write “the plain truth”. Disguising her gender had also had its benefits, as she wrote to George Henry Lewes:

“I cannot when I write think always of myself – and of what is elegant and charming in femininity – it is not on those terms or with such ideas I ever took up my pen – and if it is only on such terms my writing will be tolerated I shall pass away from the public and trouble it no more. Out of obscurity I came – to obscurity I can easily return.”

But Charlotte’s fame and appreciation of her and her sisters writing would only grow, and it is under their birth names that they are known and celebrated today. Their home at Haworth has become a site of literary pilgrimage and their works continue to be read, studied and re-interpreted.

The library’s exhibition ‘Pen Names’ explores a range of writers working in Britain from 1800 to the present day who published under pen names. It is on from 8 July 2022 to 29 April 2023. For more information see here. For more blog posts about authors who use aliases search #PenNamesNLS.

Links/Further reading:

Christine Alexander, ‘Brontë, Charlotte [married name Nicholls]’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (available through e-resources)

Juliet Barker, The Brontës, 2010 (shelfmark: PB5.211.77/1)

Brontë Parsonage Museum https://www.bronte.org.uk/

Carmela Ciuraru, Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms, 2011

British Library, Review of Jane Eyre by Elizabeth Rigby https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/review-of-jane-eyre-by-elizabeth-rigby

Sally Shuttleworth, Jane Eyre and the 19th-Century Woman https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/jane-eyre-and-the-19th-century-woman

Letter of John Gibson Lockhart to his daughter Charlotte discussing ‘Jane Eyre’, December 1847 (shelfmark: MS.1556 ff.180-181)